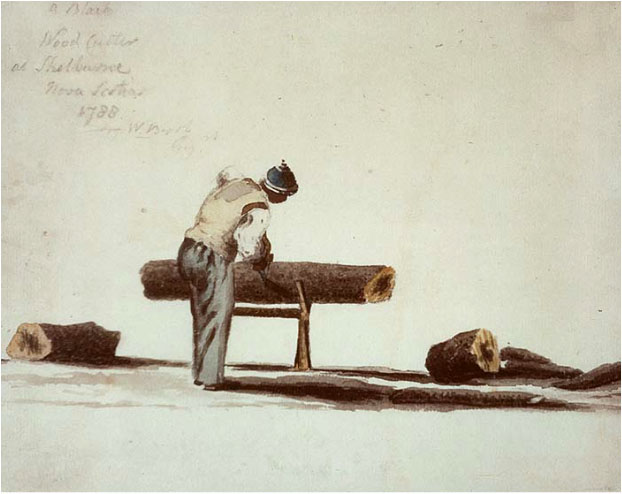

blacks/

slavery

Blacks – Slavery

From Encyclopaedia Canadiana – Volume 9 |

“… Slavery was never a major factor in the development of Canada but the marketing and use of slaves was common until the beginning of the nineteenth century. French explorers and fur-traders accepted the practice of the Indians who frequently held as slaves men and women captured in tribal warfare, and purchased Indian slaves (called panis, from the Indian tribe name Pawnee) for their own use. Negro slaves were imported into the colony early in the seventeenth century, and in 1689, at the request of the administration, Louis XIV authorized their importation from the West Indies to relieve a labour shortage. From then until the cession of the colony, Negro slaves were employed, largely by merchants and fur-traders, throughout Canada. The system was sufficiently widespread to persuade Jeffrey Amherst to include in the articles of capitulation, signed at Montreal in 1760, a clause guaranteeing that ‘Negroes and Panis of both sexes shall remain in the possession of the French and Canadians to whom they belong.’ After the Conquest, slavery became more firmly established. In Nova Scotia the British who settled at Halifax in 1749 brought with them a large number of slaves; by then opulent classes in the colony and in Canada were actively committed to the system. The migration of American colonists during the Revolutionary period resulted in a further influx of negro salves. By the end of the century however, anti-slavery sentiment was becoming more marked . . . In Nova Scotia as early as 1787 the legislature refused to accept a clause respecting slaves in an act regulating servants, on the grounds that slavery did not exist in the colony; and the courts invariably interpreted the law against the interests of slave owners. A similar situation existed in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland. After 1800, public sentiment in the British colonies in North America was so pronouncedly opposed to the slave system that only minor vestiges persisted, and these were erased by the formal abolition of slavery by the British Parliament in 1833. Indirectly, slavery continued to affect Canada until its abolition by the United States. During the War of 1812 – fourteen Negro slaves had fought in Canada and had come to learn of the freedom they could enjoy there. An Underground Railroad was established by which slaves from the southern United States, aided by abolitionists in the North, were enabled to escape to Canada. Most went to Upper Canada but some found their way to the eastern colonies. “

From Journal of the New Brunswick Museum 1979 |

Excerpt from Pages 45 to 50

The Story of New Brunswick’s Black Settlers: 1700 – 1820 by Hazel C. Hazen

“… The Loyalists who came to new Brunswick had all been promised grants of land, food and provisions for three years. But difference in colour played a big part in land granting – blacks soon learned the best land was reserved for whites. Although the vast majority of blacks were illiterate a few among the slaves had been taught to read and write by owners. Some of these were among first to receive their freedom. Once freed, a former slave had nothing but his freedom, as evidenced by the following petition received by Governor Carleton, Dated 1785, it reads in part:

‘ The humble petition of William Fisher and a Black man most humbly sheweth that having left New York in year 1783 and came in ship Peggy … in July … I then joined Captain Walker’s Compound at the same time as his servant having since gotten my freedom from his lady. I have since I came to myself got no provisions or any sign of it or any land nor neither have I received any one article that is allowed from government to poor indegent Loyalists hoping your Excellency will take it into consideration and will grant me same as is granted to all other Loyalists.’

From The History of Blacks in New Brunswick has Moments of Glory and Shame by Mark Tunney |

“… Blacks have rarely been given their own voice in New Brunswick. While there are records of blacks here before 1783, most came with the Loyalists. Some came as slaves or indentured servants, others as free blacks and black Loyalists. For most, New Brunswick did not turn out to be the top of the mountain. According to The Blacks in New Brunswick by W. A. Spray, ‘servants’ were commonly sold at auctions with cattle and other household items in 19th century New Brunswick. Advertisements such as the following were common:

‘TO BE SOLD A likely healthy negro wench of about 17 years of age, is well calculated for the country, sold for want of employ. The title is indisputable if not sold within 8 days from the date hereof by private sale, she will be sold at private auction’.

Zimri Armstrong was a black man who served with a Loyalist regiment. He felt he was entitled to provisions and land when he came to New Brunswick. But he had agreed to be an indentured servant for two years to Loyalist Samuel Jarvis. According to Armstrong, Jarvis was to purchase the freedom of Armstrong’s family and pay his passage to New Brunswick. At the end of two years Jarvis was to set up Armstrong in a trade. But Jarvis returned to the States and his brother John claimed Armstrong as his servant. While in the States, Jarvis sold Armstrong’s wife and children as slaves. Armstrong appealed to Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Carleton. But the governor, who oversaw a council of slaveowners, said he could do nothing. Armstrong, who had no money and could barely write, would have to take his case to the courts. Zimri Armstrong came to New Brunswick with promises, but he lost his freedom and his family. There is no further record of him.

Other blacks came as freemen and were promised land grants. In most cases they were given land far from the white settlements with no means of communicating with Saint John. They could not vote. Thomas Peters – an escaped slave from North Carolina who was a sergeant in the Black Pioneers regiment that fought with the British – became the leader of blacks in New Brunswick. He pressured the government in Fredericton to live up to its promises to black Loyalists, but they refused to allow him to represent other blacks. Despite the great risk of being sold into slavery by unscrupulous sea captains, he took passage to England where, with the help of abolitionists, he was able to forward a petition to the British government demanding land for 100 black families. In London he heard of the Sierra Leone Club – which hoped to form a settlement of free blacks in Western Africa. He returned to New Brunswick a hero and helped organize he move of 1,090 free blacks from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone. After arriving in Africa, he was accused of stealing money from the chest of a dead man. He was found guilty, fell ill shortly after, and died. Still, he is considered one of the fathers of that nation.

All early New Brunswickers did not march to the same drum. Quakers settled in Beaver Harbour in Charlotte County in 1783. At the top of their settlement agreement in large letters it said: ‘NO SLAVE MASTERS ADMITTED’. No one in the settlement was allowed to traffic in slaves. At the time, Beaver Harbour was probably the only settlement in British North America where slavery was outlawed. As New Brunswick historian W. F. Ganong wrote: ‘No slavemasters admitted’, to my mind makes that page one of the most magnificent in all our history”.

From The S. J. Gazette and Weekly Advertiser |

“FOR SALE A stout, likely, and very active Young BLACK WOMAN late the property of John H. Carey: She is not offered for any a fault, but is Singularly sober and diligent Enquire of James Hagt.”

October 3, 1788

From The Royal Gazette and New Brunswick Advertiser |

“… Tuesday, March 28, 1786 FIVE DOLLARS REWARD Run away, a negro man named BEN, about 30 years of age, the property of Captain Jones, had on when he went away a light brown jacket, a plaid waistcoat, corderoy breeches, white stockings, and a round hat, is about 5’6″ high, stout and well set, has very black thick lips… whoever takes up the said negro and delivers him to James Moore near Fredericton or, secures him that the owner may get him again, shall have the above reward, and all reasonable charges paid”.

From The Davidson Papers New Brunswick Museum |

“… Negroes on Miramichi – John Stewart had a negro servant named Beckwith Smith. Two men James Walsh and John Willson Jr. were charged before the Quarter Sessions of Peace at the January 1790 Session with assaulting and beating this negro servant. They pleaded guilty and were fined 10 s each and costs.”