commodore george walker

Commodore George Walker

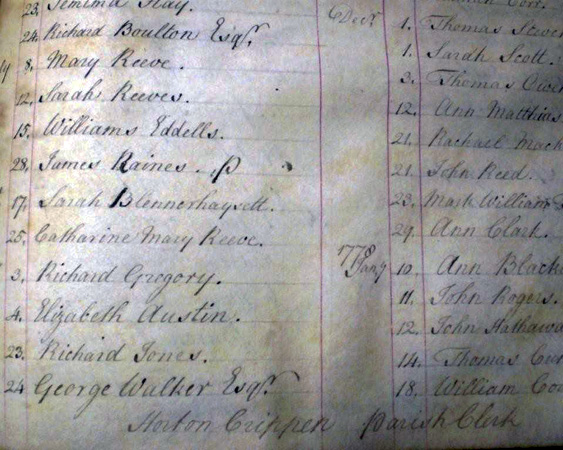

An excerpt from the National Maritime Museum record for the Commodore George Walker painting (shown above) is provided below:

“A three-quarter length portrait of the famous privateersman George Walker. He wears a blue jacket with gold braiding and buttons, red waistcoat, necktie and brown wig. Walker is shown standing in front of a rock and gesturing with his left hand towards a sea action taking place in the distance on the right. His right hand rests on a globe just above a partly legible inscription ‘F…… Gib…l…C. St. Vin’.

This portrait probably commemorates one of Walker’s successful actions capturing a Spanish treasure ship, the ‘Glorioso’, near Cape St Vincent. He had command of the ‘King George’, a 32-gun frigate which formed part of a squadron of four privateers ‘King George’, ‘Prince Frederick’, ‘Duke’, and ‘Princess Amelia’. Collectively known as the Royal Family, they had been cruising for nearly a year and made considerable prize money. In July 1747 they sailed from Lisbon and on 6 October sighted the 70-gun Spanish ship ‘Glorioso’ heading for Cape St Vincent. Guessing that she was laden with treasure, Walker attacked. After an action lasting several hours the ‘Glorioso’ was finally captured by another ship, the ‘Russell’ and escorted into Tagus under Walker’s guidance. It is probably this event which is shown in the painting.

Walker is generally regarded as the most successful British privateer. A resourceful and innovative seaman, he always carried musicians on board, and cared for his crews who in their turn respected him. Very little is known of his subsequent life, though the syndicate that owned the Royal Family did not honour their debts to him and he was imprisoned and then declared bankrupt. He died on 20 September 1777 at Seething Lane, in the City of London, and was buried at All Hallows Barking, Great Tower Street, London.”

From Dictionary of National Biography Volume LIX Edited by Sidney Lee |

Excerpt from Pages 56 to 58

“… WALKER, GEORGE (d. 1777), privateer, as a lad and a young man served in the Dutch navy, and was employed in the Levant apparently for the protection of trade against Turkish or Greek pirates … In 1739 he was principal owner and commander of the ship Duke William, trading from London to South Carolina, … The coast of the Carolinas was infested by some Spanish privateers, and, in the absence of any English-man-of-war, Walker put the Duke William at the service of the colonial government … and succeeded in driving the Spaniards off the coast. Towards the end of 1742 he sailed for England with three merchantmen in convoy. But in a December gale, as they drew near the Channel, the ship’s seams opened, … and with the greatest difficulty she was kept afloat till Walker, with her crew, managed to get on board one of the merchantmen. This was in very little better state, and was only kept afloat by the additional hands at the pumps. When finally Walker arrived in town, he learned that his agents had allowed the insurance to lapse, and that he was a ruined man. For the next year he was master of a vessel trading to the Baltic; but in 1744, when war broke out with France, he was offered the command of the Mars, a private ship of war of 26 guns, to cruise in company with another, the Boscawen, somewhat larger and belonging to the same owner. They sailed from Dartmouth in November, and on one of the first days of January, 1744-5 fell in with two homeward-bound French ships of the line, which captured the Mars after the Boscawen had hurriedly deserted her. Walker was sent as a prisoner on board the Fleuron. On 6 Jan. the two ships and their prize were sighted by an English squadron of four ships of the line, which separated and drew off without bringing them to action. The Frenchmen, who were sickly, undermanned, and had a large amount of treasure on board, were jubilant and boastful; but they treated Walker with civility, and he was landed at Brest as a prisoner at large. Only the very next day the Fleuron accidentally, or rather by gross carelessness, was blown up, and a letter of credit which Walker had was lost. He was however, able to get this arranged, and within a month was exchanged. On returning to England he was put in command of the Boscawen, and sent out in company with the Mars, which had been recaptured and bought by her former owners. The two cruised with but little success during the year, and, coming into the Channel in December, the Boscawen, a weakly built ship, iron-fastened, almost fell to pieces; and only by great exertions on the part of Walker was preserved to be run ashore on the coast of Cornwall. It was known in London that but for Walker’s determined conduct the ship would have gone down in the open sea with all hands; and he was almost immediately offered a much more important command. This was a squadron of four ships – King George, Prince Frederick, Duke, and Princess Amelia – known collectively as the ‘Royal Family’, … The prestige of this squadron was very high, for in the summer of 1745, off Louisbourg it had made an enormously rich prize, which, after the owners share of £700,000 was deducted, had yielded £850 to each seaman, and to the officers in proportion … After cruising for nearly a year, and having made prizes considerably exceeding £200,000, the Royal Family put into Lisbon; and sailing again in July 1747, had been watering in Lagos Bay, when on 6 Oct. a large ship was sighted standing in towards Cape St. Vincent. This was the 70-gun ship Glorioso, lately come from the Spanish Main with an enormous amount of treasure on board. The treasure, however, had been landed at Ferrol, and she was now on her way to Cadiz. Walker took for granted that she had treasure, and boldly attacked her in the King George, a frigate-built ship of 32 guns. Had the other members of the Royal Family been up, they might among them have managed the huge Spaniard; as it was, it spoke volumes for Spanish incompetence that in an action of several hours’ duration, in smooth water and fine weather, the King George was not destroyed. She was, however, nearly beaten; but on the Prince Frederick’s coming up, the Glorioso, catching the same breeze, fled to the westward, where she was met and engaged by the Dartmouth, a King’s ship of 50 guns.

The Dartmouth accidentally blew up with the loss of every soul on board except one lieutenant; but some hours later the 80-gun ship Russell brought the Glorioso to action and succeeded in taking her. The Russell was only half manned, and was largely dependent on the privateers to take the prize into the Tagus. One of his owners, who had come to Lisbon, gave Walker ‘a very uncouth welcome for venturing their ship against a man-of-war’. ‘Had the treasure’, answered Walker, ‘been aboard, as I expected, your compliment had been otherways; or had we let her escape from us with that treasure on board, what had you then have said’? The Royal Family continued cruising, with but moderate success – for the enemy’s ships had been wiped off the sea – till the end of the war. Altogether, the prizes taken by the Royal family under Walker’s command were valued at about £400,000. After the peace Walker commanded a ship in the North Sea trade, but either lost or squandered the money he had made in the Royal Family. He got involved, too, in some dispute with the owners about the accounts, and was by them imprisoned for debt shortly after the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War. How long he was kept a prisoner does not appear, but he had no active employment during the war. He died on 20 Sept. 1777.”

From The Voyages and Cruises of Commodore Walker During the Late Spanish and French Wars |

Introduction and Notes by H. S. Vaughn 1760Extract from Introduction Pages XI to LI“… Little is known as to the origin and authorship of this very scarce work. It has been inferred from statements in the narrative that it was written by one who accompanied Walker in all his cruises except that of the Boscawen, but in no instance is a clue given as to the share taken by the writer in the various enterprises … At the time of publication the hero had been unjustly detained in a debtors’ prison for four years, and his case having come before the House of Commons in connection with proposed legislation for the relief of bankrupts, the suitable moment had arrived for arousing public interest in his career … The essential facts are corroborated by history … A period of some twenty years in the middle of the eighteenth century must be regarded as the golden age of British privateering, alike from the immense value of the prizes taken, the striking nature of the exploits performed, and the character of the commanders employed. Captain Walker, only a privateer it is true, but a man of a type that was to be justified in the royal service a few years later by Hawke and his great successors. Clear-headed, determined, and always sure of himself in a way that carried his people with him, Walker’s professional skill and knowledge of affairs combined to make a rare character. He was what the French call ruse, – an artful or subtle man, – and how often this quality pulled him, his men, and his owners out of difficulties the narrative will presently show. Add to these attributes a dry but kindly humour and a persistent cheerfulness, and you have a type that would have been invaluable in the regular service of his country at that very period. Unlike the French, however, the British navy admitted of no entry from the merchant service except in a rank so junior as to be, for Walker, out of the question, so that he remained to the end of his life without official recognition; and being without interest, and never having acquired the high art of improving his own fortunes by intrigue or bluff, he died in comparative obscurity. Instructions for privateers were issued by the Government from time to time, and affected all such matters as manning and equipment, wearing of colours, conduct towards neutrals, procedure as to prize, ransom, disposal of prisoners, etc. Every commander had a copy of these instructions, and he was bound by them to render a copy of his journal to the Secretary of the Admiralty … The men themselves came from much the same classes that manned the King’s ships and the merchant service, that is to say they were in part of seafaring habit and in part landsmen, but they were all volunteers and not pressed men. The privateer usually secured the pick of the ‘prime seamen’ and had a great advantage in popularity over the other services. Discipline was less severe than in the navy, and in many of the smaller ships it was very loose … The prospect of prize money was the great attraction to the privateer recruit, and the individual share among officers and men was far greater in proportion than that to be obtained in the navy, the object of the cruise being frankly the enrichment of the owners and ships’ companies at the expense of the enemies of the State … In the case of the Royal Family privateers it was agreed that the officers and seamen should have one half of the prizes in lieu of wages, to be divided among them in stipulated proportions. The system was confirmed by Royal Proclamation in 1744 … ‘Private plunder’ was restrained as far as possible by strict commanders like Walker, but it was an additional attraction to the privateer service. The value of the cargazon, or lading of the ship, when sold, was divided into shares and dealt with according to the agreement. Private stores such as clothing or foodstuffs became free booty to the seamen; this was the old law of Pillage … ‘private plunder’ sometimes helped out the privateersman’s kit. When the Revenge returned to Liverpool in 1756, from a successful cruise, her crew, ‘made a handsome appearance’ when they came ashore, ‘each man having on a clean French ruffled shirt, which they had taken on board a vessel bound for Bayonne’ … The smart and popular type of privateer of 1740 was the 20-gun ship of 300 to 400 tons. A few owners fitted out suitable vessels of 500 tons or more; Walker’s Boscawen ran to 600, but she was a French prize, the frigate Medee taken by Boscawen himself in the Dreadnought … The business of the privateer was not to engage the enemy’s navy but to prey upon his commerce … As a rule the control of wages, slops, and victualling was in the captain’s hands, but Walker when commodore of the Royal Family, carried a captain’s clerk and also a chaplain…Walker makes his earliest appearance – in a ghost story – as captain and owner of the merchant ship Elizabeth at Cadiz, in 1734. His previous service in the Dutch navy against Mediterranean corsairs remains obscure and does not affect the story of his privateering voyages except that he came to them equipped with knowledge of affairs and warlike experience. So we ‘take him up’, as the narrator puts it, in the year 1740, when he and his fellow owners of the ship William took out a letter of marque for a trading voyage to the Carolinas … the ship could at short notice be turned into quite a respectable privateer and this is what happened when they reached the Carolinas. In the meantime the William lying at Newcastle, was chartered by the contractor for victualling the garrison of Gibraltar to convey pork to that station. Two other ships, the Sea-Nymph and Hannah, laden with beef, peas, bread and flour, were despatched at the same time, and, as no man-of-war is mentioned, it may be assumed that the William acted as convoy to the other two. Well armed but under-manned for fighting, Walker saved his ship from capture by a Spanish privateer off Cape Finisterre by means of a clever trick which had been thought out in advance. He took with him a parcel of Marine clothing which no doubt included the red coats and fusilier caps that were the distinctive features of the uniform of the Marine regiments at the time. With these he dressed up his handspikes and other utensils so that as he says, ‘our fictitious soldiery served at first to intimidate the enemy’ and gave the Spaniard the impression that he was up against a King’s ship … Arrived in American waters they found the coast of North Carolina defenceless and the colony was glad to accept Walker’s offer of the William to protect the trade … An Account of Charges for this affair shows that it cost the Province altogether £10,000, a considerable sum for those days. £5,441 of this was for ‘Hireing and fitting out with Victuals and Men the ship William of London, Captain George Walker, commander from Cape Fear to Ocacock Inlet, for the relief of the inhabitants of these parts from some Spanish privateers that lay there taking all ships coming in and out of the said inlet, destroying cattle ashore and devastating the country’. Walker’s share for the charter-party was £2,680, and the hire of two sloops cost £68, but no other details are given except £27 for ‘Linen cut up for Bandages’. Evidently it was a bloodthirsty little job! … Governor Johnston, who with the Assembly passed a vote of thanks to Walker on behalf of the Colony was a Scotsman, educated at St. Andrews. He reigned from 1734 to 1752 and had a high reputation … Walker refused the offer of land which was made to him and no doubt in the years of his misfortunes thought of it with regret…Reverting to the status of a trader, letter of marque, Walker visited Barbadoes for a cargo … They sailed from Barbadoes October 31, 1742, with a convoy … Walker’s little fleet was scattered by a hurricane while he himself was at death’s door with dysentery, but he made a surprising recovery in the face of danger. The stratagem of the mizen mast was in his best manner and was happily successful, and so they reached Dover on New Year’s Day, 1742/3, only to find that although fortunate in affairs of the sea, ill luck had attended him in matters of finance. Soon after the loss of the William the former owners set forth a snow of 130 tons and 4 guns, called the Russia Merchant, and in command of her Walker made three trips up the Baltic within the year … The relation of the Baltic experiences is suggestive of the theory that the ‘Voyages’ may have been written by himself. Incidentally, the language is crisp and picturesque and such as Walker used in conversation. What prettier and simpler description could you have than this? ‘In the run home he met several small privateers, like birds, scudding about the seas; who all scoured from him at his appearance as one of great prey’ …… owners now offered him the command of the Boscawen … Boscawen finally sailed from Dartmouth, April 19, 1745, – ‘the most compleat privateer ever sent from England’ … A month afterwards, cruising well in the track of the homeward bound West India fleets, north-west of Finisterre, they fell in with the Sheerness privateer of London, Captain John Furnell, 440 tons, 26 carriage and 12 swivel guns, 200 men, a useful craft with some reputation. At dawn the next morning the pair sighted a fleet of eight French letter of marque ships from Martinico, well laden and armed. Walker made straight for them, and the enemy, mounting in the aggregate 120 guns to the Boscawen’s 30 (although it is true they were mostly of smaller calibre) formed line and waited for him … After lying-to for forty-eight hours, to repair damages, they proceeded to Bristol with the prizes and prisoners. Walker entertained the latter handsomely, even to the extent of giving an old lady a silk nightgown, some fine linen waistcoats, cambric night-caps, etc., in which she appeared ‘a kind of Hermaphrodite’ … Two days after their arrival the privateers received the following letter from the Admiralty:31st May, 1745My Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty being informed that you and the Boscawen Privateer are arrived at Bristol with 5 sail of French ships you have taken which were bound from Martinicoto France, Their Lordships are very glad to hear of your good success, and command me to congratulate you thereon and desire if you meet with any papers in those Prizes that give any light into the proceedings or designs of the French at Martinico that you will immediately send the same hither by express. I am, etc., T. Corbet. Capt. Furnell, Sheerness Privateer, Bristol. Capt. Walker, Boscawen. The privateersmen, elated with their good fortune after so short a cruise, ‘painted the town red’ in the usual manner, and even Walker devoted both time and money to the entertainment of his French prisoners. In fact, the ‘facetious old lady’ appears to have enjoyed herself immensely, in spite of her misfortunes, and took upon herself to instruct the local milliners and dressmakers in the ‘polite cuts’ of the French fashions, a proceeding which must have caused an immense fluttering in the dove-cotes of Bristol and Bath, and was no doubt very good for trade. Walker solicited the favour of travelling in the lady’s coach as far as Bath, – with a view of showing her the town. No sooner had they set out upon the road than there fell in behind them as escort a cavalcade of ‘honest tars’, who, having heard that their captain was going to Bath with the French lady, ‘were determined every one to shew it to their ladies also, as every one who had not a lady of his own, had bought or borrowed one for the time’. To do the thing in style they had hired every kind of horse and vehicle in the town and bought up all the coloured ribbons they could find, with which they decorated impartially their own hats, the rumps of their horses, and the bosoms of their ladies. ‘Never sure were horses, whores, and ribbands so dear in one day at Bristol’. Moreover, each mariner flew an ensign, jack, and pendant aboard his own craft, and paid the compliments of the sea to the captain and the lady upon taking up station. Needless to say this was all to the great pleasure and delight of the old lady, who was ‘very sedulous in returning the compliments of the salutation as they huzzaed and passed’, but it must be confessed the French Commodore was a bit touchy about it, until Walker smoothed him down. If there is a more rollicking tale than this in the annals of Jack ashore I do not know it; one would like to have had a contemporary picture of these merry doings! The second cruise of the Boscawen commenced in dispiriting circumstances. An old ghost story, connected with the ship’s history under the French flag, had somehow been revived, – whether through the malice of some discontented person, or how, it is impossible to say – and this reacted upon the spirits and endurance of the ship’s company during the whole commission. These forebodings were justified. After the capture of a French snow and the temporary detention of a neutral Walker was faced with a mutiny partly due to his action in releasing the latter. He treated the malcontents with forbearance, explaining the law on the subject, exhorting them to their duty, and arresting only four of the mutineers. This sufficed for the time being, but at Madeira he had further trouble, on account of the misconduct of some of his men, who publicly insulted the congregation and their religion at a church in the town. Unhappily, this particular kind of hooliganism was only too common in the eighteenth century on the part of Englishmen abroad. A bad instance was that of Admiral Mathews, who decorated his monkey with a crucifix, as described in Mann’s letter from Florence to Horace Walpole in September, 1742. Other cases occurred in Lisbon, in 1753/6. Walker’s tact, and his gift of ‘blarney’, enabled him to calm the local indignation. The Boscawen sailed October 5, with the French prize, now the George tender. The latter deserted on the night of the 21st; her captain, Kennedy, first lieutenant of the Boscawen, went off with her to Ireland and there sold the greater part of her wines. He returned with her afterwards to Dartmouth ‘with some vague excuses for his behaviour’. The Boscawen, left alone, came up with the Duke of Bedford privateer of Bristol, and was in her company in very hard gales when the first catastrophe occurred. The mainyard, with sixty men on it, fell on to the gunwale of the ship, the terrible concussion and increasing gale causing her to labour hard and work. The story of a ship in such conditions has seldom been better told than in this book. Butts and planks started, partly owing to inferior construction and partly to her overweighted condition, and she was only preserved from foundering by Walker’s indomitable spirit in keeping his officers and men at their task. There are few more moving passages in the book than that in which we are told how his drum beat to arms and he called upon his officers to face the enemy – their own fears. Finally, leaking like a sieve, she drove into St. Ives Bay, with her anchors gone and no hope except to get within shelter of the pier … the Boscawen went ashore and broke up, with the loss of only four hands. ‘Thus fell a wreck the finest privateer in Europe’, but not without honour to all concerned … Walker’s reputation was enhanced as much by his fortitude and determination in this disaster as by his previous successes against he enemy, and his owners not only received him with every mark of esteem but offered to build especially for him a forty-gun ship, to be fitted out according to his requirements. Unhappily, as it turned out for the security of his own fortunes, private reasons which are not disclosed induced him to sever his relations with Holdsworth and Terry and proceed to London, where he ultimately entered into an agreement with a syndicate which proved to be less considerate and scrupulous.We now come to the story of the Royal Family privateers with which Walker’s name is particularly associated as Commodore during those successful cruises that created at the time a great sensation in this country … the famous Royal Family – King George, Prince Frederick, Duke and Princess Amelia – under the command of Commodore Walker. The expedition opened in a way that augured none too well for its success. The ‘old Boscawens’ rolled up with hundreds of other prime seamen to join Walker’s flag at Bristol, but the conduct of the management in regard to the new terms and articles was anything but straitforward, and it inspired both officers and men with distrust … Walker’s first prize was the armed polacre Postillion de Nantes, 90 tons, which he took out of Safi Bay near Cape Cantin, the southern limit of their assigned cruising station. The reference to combustible stink-pots in the account of this sharp little affair may remind us that gas bombs are not altogether a new invention. The prize’s cargo (beeswax and other goods) was sold for L1,743, and the vessel herself was converted into a tender under the name of Prince George, for the remainder of the cruise. They were now ordered to cruise between the Azores and the Banks of Newfoundland, and on July 5 they fell in with the Prince Frederick which had been left to dock at Bristol in May. There follows an interesting account of Terceira and of some festivities in which the officers and gentlemen of the four ships took part; the Commodore’s band of music entertaining the company and reflecting much credit on the visitors. The horns and flutes which had delighted the old French lady in the Boscawen were now supplemented not only by a black drummer but by, ‘an hand from England of great execution on the large or Welsh harp (an instrument not much in use but excelled by none) and a performer on the violin who was reckoned the second in England’…On October 17, 1746, Walker arrived at Lisbon with his convoy and began preparations for the remaining half of the cruise. Trouble awaited him in the bad quality of the sea provisions, which, it is hinted, was due to some rascality on the part of the management at home, but his care for the frequent cleansing of the internal parts of the ship with vinegar and the supply of green vegetables and fresh meat as often as possible resulted in the preservation of the health of his men … Walker’s intelligence department was well served and the results of the cruise were satisfactory, the chief prize being the Spanish register ship Nostra Senora del Buen Conseijo, Cadiz to Buenos Ayres, 24 guns and 150 men, with a cargo of L150,000. She had on board three governors with their ladies and families, and other passengers who had private adventures to the amount of L27,000. The Commodore behaved in his usual handsome manner towards the prisoners, thus, as in the Boscawen, establishing friendly and amusing relations from which we gain the story of the lap-dog and the monkey, the lady and the lover … The Nympha was the last prize captured by the Royal Family in their first cruise, which resulted in ‘taking four prizes, then valued at a reasonable estimation, greatly upwards of L220,000, without the loss of a man killed’ …The news of the first successes of the Royal Family created a sensation in London and Bristol, and preparations were now begun for the second cruise, which led to the zenith of Walker’s career and included his famous fight with the Glorioso … The little fleet of six ships, mounting 114 carriage guns and manned by 1,000 men, set forth upon its last cruise on July 10, 1747 … The first prize taken was a Spanish tartan laden with money and cocoa from the West Indies transhipped at the Canaries: … The Glorioso, a 74 gun ship with a crew of 700 was on her way from Havannah to Ferrol with treasure said to be worth three millions sterling on board. As if to make Walker’s daring all the more conspicuous, she had already twice encountered on her voyage groups of ships of the British navy and on both occasions had defeated them…The sorely tried Glorioso now approached the fate which, one cannot help feeling, she deserved to escape. The Royal Famly standing out of Lagos Bay, October 6, 1747, after watering, discovered her plying to the northward towards Cape St. Vincent on a N.E wind. Here the ‘Cape of Surprises’ – the cape of many battles – was to witness yet another scene of carnage and destruction … Seeing her enemies the Glorioso bore away again to the westward and after a chase of five hours the King George came up with her, when all of a sudden it fell a dead calm in which they lay within gun shot of each other …The action began at eight o’clock ‘on a clear moon-shine evening’ and lasted more than three hours yard-arm to yard-arm during which ‘the castle upon Cape St. Vincent fired very briskly as a neutral power commanding peace; and we, being the nearest to it, received many of its shots’. Thus belaboured by her huge antagonist and the neutral fortress the little King George carried on the fight alone for two and one half hours, when the Prince Frederick came up and the Glorioso concluded it as time to go. Walker was in no condition to follow her, but as his other ships, delayed by lack of wind, arrived, he sent them in pursuit. And then, so that the leviathan, for all her gallant defence, should have no chance at all, Fate decreed that two of his majesty’s ships should turn up from opposite directions, sailing to the sound of the guns, – the Russell, 80, and the Dartmouth, 50. As, in the course of this history, it has been necessary to mention occasions on which the conduct of the king’s ships showed to disadvantage, it is pleasant to chronicle instances to the contrary. The Dartmouth approaching from the westward, headed off the big Spaniard and engaged him single-handed for an hour and a half, while the Russell and the privateers from the eastward were coming up, when, unhappily, she blew up owing to some carelessness or accident in her magazines. The log of the Russell records that they came up with the chase at one a.m. when ‘the action began as warmly on both sides as we were able to load and fire and so continued till 6:30 in the morning when a lucky shot from us carried away his main topmast, upon which he directly struck. From first to last we were within musquet shot of each other, we sailed large al the time the action continued. Hailed him to hoist out his boat, but he replied he could not as all his rigging was cut to pieces (as was ours), so that we had to wait till one of the privateer’s boats came on board, when we sent for the captain who gave us an account that our Prize was the Glorioso …’.So ended the prolonged and desperate struggle of the Glorioso against her many enemies. ‘Never’, as Walker says, ‘ did Spaniards, nor indeed men, fight a ship better than they did this’ … Crawling alone, and in a crippled state, towards Lisbon, the King George met a ship which they judged to be a French man-of-war of 60 guns, and the indomitable Walker at once set about preparations for fighting her. Luckily, she proved to be the Bedford, 70, Admiral Townshend, and so Walker had fought his last battle. The Royal Family, the Russell, and the prize were shortly afterwards re-united at Lisbon … The dissolution of the Royal family was now at hand. Parting company off the Rock of Lisbon the other ships went home and the Commodore took the King George into the port on March 25, 1747/8. A month later the war ended in the unsatisfactory peace of Aix la Chapelle … Having defeated all his enemies at sea Walker was to find it more difficult to dispose of those on shore. A state of confusion had arisen between agents at Lisbon and the managers at home, which boded ill for the rights of officers and men. The King George was seized by the agents for debts against the managers, and ‘the Commodore found his ship all at one slipt away from under him, the cruise frustrated, and all his men adrift in a foreign country, without money, no care had, or provision made for them, open mouthed in their abuses against the managers’. In this dilemma many of the men in disgust accepted employment in Portugal and Spain, and Walker himself was approached with an offer from the King of Portugal of the command of a ship of war, in whose service he would, no doubt, have risen to high rank. It speaks volumes for his patriotism and his simple trust in his countrymen that he refused…Upon his arrival in England, at the end of the war, Walker, secure in the belief that he was entitled by his exertions to a modest fortune, took up with enthusiasm the cause of the revival of the British fisheries, which was then beginning to occupy public attention. In it he sank most of what he possessed before any distribution from the accounts of the Royal Family was made … In October, 1750, a Royal Charter was issued incorporating the Society of the Free British Fishery … Of this body the Prince of Wales was Governor and the Council included many men of distinction … The project proved a failure, the reason for which is probably to be found in Walker’s remark that he ‘found Party contending for a majority in it, and Inexperience presiding at the board’. Capital of L104,000 was raised within eighteen months and in 1756 the Society possessed thirty busses, the crews being drawn chiefly from the Orkneys. Financial and other difficulties were encountered, some of the vessels being taken by French privateers, and the remaining boats and other effects were sold in 1772 for L6,391. Meantime Walker was doing work of permanent value, not only towards reviving the fisheries of the herring – … but also of the cod and the ling. On June 23, 1749, we find that ‘Capt. Walker, late Commander of the Royal Family Privateers, in the Baltimore sloop, having on board several gentlemen appointed to fix on proper places for establishing a fishery on the coast of Scotland, fell down the River to Gravesend, and is bound to the Isles of Orkney and Zetland for that purpose’ … From the Orkneys and Shetlands he sailed down the west coast visiting the islands, sounding the harbours, and obtaining a mass of information as to resources, food, fishing and other industries … Contemporary pamphlets embodied much of his results and one of them contains the following, with which the reference to this subject may be concluded: ‘Captain Walker, late commander of the Royal Family Privateers, in which station he behaved with uncommon Conduct and Bravery, is about taking a long lease of the Isle of Arran for himself and some other gentlemen in order to improve it for the Fishery; a most laudable example of true Patriotism, first boldly to wage war with the enemies of this country and then to employ the Reward of his Dangers and Toils in improving the same at home’…In order to complete the story of Walker’s career as far as possible, to vindicate the memory of a man who deserved well of his country, and to show what risks the privateersman ran, not only from battle and shipwreck alone, but from dishonest owners, original sources have been closely studied, and the story may be told briefly as follows … trickery prevailed on the part of the managers towards the officers and men of the Royal Family … On returning with their booty great numbers of men were, at the alleged instigation of the owners, impressed for the navy and never received their prize money, which, instead of being divided in the stipulated manner, was deposited in the Bank of England and made subject to an order of the Court of the Chancery. In 1749 some of the sailors filed a bill in Chancery, demanding an account, and in 1752 the Master of the Rolls made a decree in their favour. The owners, however, raised dilatory pleas, and the plaintiffs, through lack of means, were unable to pursue their claims with vigour. The hearings lasted till 1810, when on technical grounds the matter was dropped. Bad as the fate of the common men, the treatment of the Commodore, whose brains and bravery had provided this huge fortune for the owners, stands alone for mean rascality. The old-fashioned sailorman was a child in regard to figures and finance, and he certainly delivered himself bound into the hands of the Israelites on this occasion. The prizes having been condemned and sold for £200,000, the owners became debtors to Walker for his share and allowances as ‘Commander-in-Chief and Quartermaster’ of the Royal Family and also on account of the sum of £7,247 for advances made by him to the officers and men at Lisbon, for which he had lodged the vouchers with the owners. Nothing having been paid, Walker applied to them in 1749 for an advance of £2,550 to finance his fishing scheme referred to above. To obtain this he was trapped into signing a bond which assigned to them his interest in the prizes, £2,878 and also the £7,247 advanced by him until the loan was repaid. Walker, busy with his schemes, allowed things to drift, and the owners pretended the accounts were too intricate to come to any settlement; in the meantime they secretly received from the men’s agent (Casamajor) repayment of the sum of £7,247 and other moneys which should have gone into Walker’s pocket – but did not. So things drifted until 1756, when war broke out. Walker, with high hopes of further fame at sea, had been appointed to command a ship owned by John Cruikshank, a London merchant, when on the 21st May he was arrested for a debt of £800 at the suit of Belchier and Jalabert, two of the owners, and thrust into King’s Bench Prison, where he remained for four years, the first twelve months in close confinement which ruined his health. In May, 1757, he was made a bankrupt … The evidence proved that the estate of the bankrupt consisted chiefly of a very large debt due to him from the managers of the Royal Family, and, apart from that, they had omitted to give him credit for a sum by which the balance would have been in his favour instead of against him. The laws – after much delay – were ameliorated. Also, poor Walker was released from the debtor’s prison in which he had been immured on a fictitious charge. We may be sure that he emerged into the air of this ‘land for heroes’ with a heart and will unbroken by misfortune, though with health impaired.The narrative tells us no more about him except that he afterwards commanded a ship in the fishing trade and had at least one good friend at his back. Research has so far failed to throw any light on his parentage, birth, and boyhood … He has left an imperishable name as the greatest of the English privateer captains, – a man singularly modest, conspicuously sincere, brave as a lion, untiring and fearless in the performance of his duty, and clever in all things but those affecting his own pocket. The ‘Town and Country Magazine‘ for October, 1777, contains this notice of his death: – ‘Sept. 20th, George Walker, Esquire, of Seething Lane, Tower St., formerly Commodore and Commander of the Royal Family private ships of war’; and an entry in the register of the church of All Hallows, Barking-by-the-Tower, attests his burial there on September 24, 1777.”

From The Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland) Wed. May 13, 1767.

We hear that George Walker, Esq.; formerly Commander of the Royal Family privateers, is named as Lieutenant Governor of New Glasgow on America, upon the promotion of the last Lieutenant Governor to Nova Scotia.

From Additions and Corrections to Monographs on the Place-Nomenclature, Cartography, Historic Sites, Boundries and Settlement – Origins of the Province of New Brunswick by W. F. Ganong |

Excerpt from Page 144

“… Nepisiguit in 1768 and (Commodore George Walker) established there (evidently on the well-known situation on and near Alston Point) a fishing and trading establishment. While absent in England in 1770 trying to obtain a grant of these lands, a Captain Allan, who had been in Bay Chaleur for two preceding years on a man-of-war, obtained from the Nova Scotia Government the 2000 acres well known as the Allan grant …, and Walker had no alternative but to buy out his rights, which, by the aid of one Hugh Baillie of London, he did for the sum of £600. Walker and Baillie then proceeded, the latter supplying apparently the capital and the former acting as manager, to promote the settlement with great vigour, sending out between 1770 and 1773 no less than £10,000 worth of goods for trade. In 1773 all of Baillie’s rights were bought out by John Shoolbred of London, and the settlement continued to grow, so that in 1775 Walker was resident there in charge of a well-equipped establishment, employing twenty British subjects, engaged in fishing, trading, ship-building, lumbering and, to some extent, farming. Nepisiguit at this time had a population of 70 souls, apparently inclusive of Acadians but not Indians. No further information occurs in this document, but as is well known, the establishment was plundered and ruined in 1776 or 1777 by privateers from American colonies. No attempt was ever made, apparently, to reestablish the settlement.”

From Ganong Manuscript Collection Box 32 History – Pre-Loyalist Period |

Copy of Letter and Memorial of John Shoolbred and George Walker 1770 – 1775 re Bay Chaleur and Surrounding District

Bathurst – Walker.

Lent me by Gaudet To the Right Honourable

The Lord of Trade and Plantations

The Memorial of Mr. George Walker of Nova Scotia

1770 Rec. Mar 3 Humbley Sheweth’… That your memorialist, having about some years carried a large cargo of ? and a quantity of fishing implements in his own ships to America to ? the fishing trade in the ? of N. S. northward of St. Johns and having ? ? ? that ? of Trade and Commerce and est. settlements ? ?, has the opportunity experience of making .… ?’Then relates how much the country is suffering from lawlessness and want of an authority.

In an accompanying document – an account of the Bay Chaleur 1775.‘… They (Indians) have frequently came to a settlement in the Bay of Chaleur called Nepisiguit where a gentleman resides that was appointed naval officer a few years ago. he being the only civil military or Ecclesiastick officer in these parts, his ? is ? known of the Indians and upon such occasions as the following they apply to him for relief – to settle differences and disputes among them, baptize their infants, perform the ceremony of marriage and bury the dead. ? these of them that live near where he resides.’This (if correct) applies ? to Walker.At the aforesaid settlement of Nepisiguit there are upwards of 70 souls.

Document loaned me by Gaudet.London 12 June 1770? George WalkerSir’… Mr. Hugh Bailley, Doctor of Laws, and Hugh Bailley (late of Bengal) ? of London gentlemen and Allen Auld of London merchant, do hereby empower you to apply to the governor and ? of N. S. for a grant of the following lands and fisheries.30,000 ac. at Caraquet for Hugh Bailley 30,000 ac. on s. side of Restigouche for Allen Auld etc., etc.’ Lent me by GaudetEnclosure in Letters of 17th jan. 1775Campbell to DartmouthTo the Right Honble the Earl of DartmouthOne of His Majestys principal Secretaries ofState etc etc etc.The Memorial of John Shoolbred, London,Merchant’…

Humbly ShewethThat in the year 1768 Mr George Walker, who had formerly rendered Essential Services to his Country during his Command of the Royal Family Privateers, Settled in the Bay of Chaleur, in the Province of Nova Scotia.That after establishing a Trade with the Indians who inhabit that part of Acadia and Canada, and taking the proper steps to carry on a Cod Fishery on the Coast, Mr Walker after two years Residence in the Bay of Chaleur returned to England, to apply for a grant of the Land necessary for carrying his scheme into Execution.That during his absence, Capt. Allen of the Glas-gow, man of War who had been two summers at that station to protect the Fishery; applied to the Governor of Nova Scotia and procured a grant of 2000 acres of Lands adjoining the Harbour of Nepisiguit where Mr Walker had settled; and in this grant was included the very spot on which Mr Walker had erected his store houses, stages and other necessary Buildings to carry on his proposed settlement.That however cruel and ungenerous this Behaviour of Capt. Allen’s was, Mr Walker was sensible he had no alternative but to purchase his grant and being joined by Mr Hugh Baillie a gentleman of Fortune he was not only enabled to pay Mr Allen six hundred pounds sterling for his Title, but at the same time to push on the settlement with such spirit that in the years from 1770 to 1775, Mr Baillie sent upwards of L10,000 sterling in British Manufactures to the Bay of Chaleur.That soon after Mr Baillie’s affairs requiring his presence in the East Indies, he sold his whole property in the Bay of Chaleur to your Memorialist who ? ? ? the settlement at a great Expense; and flatters himself he has already put in such a footing, as will in time greatly benefit the Traders and manufacturers of his Kingdom.Your Memorialist has a Store House here well supplied with every commodity in carrying on the Peltry, and Fish Trade with the Acadians, Indians, and often Resident-Traders in the great Bay of Chaleur, and its Environs.Twenty British Subjects are now employed by your Memorialist under the direction of Mr Walker, in Fishing during the Summer and Ship Building during the Winter. They build Vessels from 50 to 300 Tons, both for Private Use, and Sale; the Iron work Cordage Sails ? of which are all sent from England.Dryed Cod, and Salted Salmon are prepared for the Mediterranean Market, Barrel’d Cod, and Mud Fish for the London consumption; and the raising of corn in no means neglected, Herring, and Mackarels with various Kinds of Lumber for the West Indies the Bay will supply, and an extensive Seal Fishery may be carried on upon the neighbouring Coast of Labrador, from whence the Bay Chaleur is distant only 60 Leagues.…The Salmon Fishery has but lately become an object of attention; the principal place for carrying it on is in the River Restigouche, which lies at the Head of the Bay of Chaleur, and has a communication with it for vessels of small burden. To this River people employed by your Memorialist have resorted, but as there are no Settlements on either side of the River, the carrying on the business in its present state is attended with much inconveniency, and often with great Loss, from the depredations of the wandering Acadians and Indians, that frequent its banks.Mr Baillie did apply by himself ? for a grant of 500 acres on that River to make a settlement, but by some means it was neglected to be expedited ? his Majestys Regulation with regard to Lands in America prevented the usual mode of application. Your Memorialist therefore Humbly Requests that he may be allowed at his own proper expence, but under the direction of his Excellency Governor Legge, to ? out and survey 500 Acres of Land on the Nova Scotia side of the River Restigouche and adjoining to the old Indian Church, paying such price as Land in that uncultivated country may be deemed worth, if your Memorialist cannot be indulged with it from His Majestys Royal Bounty.Your Memorialist has only to add, that the Lands now in his possession are settled according to the true meaning and intent of the Government, and that His Excellency Lord William Campbell has had the goodness to countenance this application to your Lordship, by a Letter which your Memorialist has the Honor to enclose, and rests his Petition in the Goodness, Justice and Impartiality of Lord Dartmouth, to whom he begs most humbly to submit it.Jno. Shoolbred.’

From Extracts From the Story of the Restigouche by George MacBeath |

Commodore George Walker

“… After departure of French, the Micmacs and probably some isolated families of Acadiens – were only residents on river. Not until 1768 did first British traders come to Bay Chaleur. First and most outstanding was George Walker, who was without doubt one of most famous persons who ever lived in to-days New Brunswick. By birth a Scot, he served as youth in Dutch navy. Then he returned to England, became Commander of a fleet of armed British merchantmen during War of Austrian Succession, and gained world fame for his exploits. After that fortunes took turn for worse, he spent time in debtor’s prison. When he decided to come to Canada he was undoubtedly drawn to rich territory of Restigouche because of wealth to be acquired from its forests and fisheries, and from Indians who were eager to trade furs and feathers from wild fowl. Set up large trading establishment in Bathurst 1768 and an outpost at Walker’s Brook, a short time later. He immediately established trade with Indians, and formed plans for engaging in cod-fishing.After building store-houses and stages for the fishery, Walker returned to England where he learned that land he had improved had just been given out as a grant. He managed to interest another Scot, Hugh Baillie, in his Restigouche trading schemes, however, and they purchased the grant for L600. During next three years Baillie and Walker built up sizeable trade in fish and furs, bringing out L10,000 in British manufacture during that period. Restigouche trade consisted largely of fish, furs and hides. Salted salmon for Mediterranean trade was apparently main export. Salmon were not caught in the conventional way, but were speared by Indians who were expert at it.1773 Baillie sold the whole of his property on Restigouche and Bay Chaleur to London merchant John Shoolbred … trade flourished and by 1775 – 20 British subjects were employed under direction of Walker who appears to have been little more than Shoolbred’s overseer at this time. American privateers made several raids in Bay Chaleur area during Revolutionary War and the Shoolbred establishments suffered extensive damage. There is a belief that Walker was commissioned by Imperial Government to protect British residents and properties on Restigouche and Bay Chaleur, but no effective defence was established. And when his own outpost at Walker’s Brook was destroyed by American privateer 1776, he abandoned it, and returned to England where he died next year.”

From Cooney’s New Brunswick and Gaspe by Robert Cooney Reprinted in 1896 |

Excerpt from Pages 171 to 179

“… from the expulsion of the French, until six or eight years . John Young – Englishmen, Mr. Robertson – a native of Morayshire in Scotland. Formerafter taking of Quebec – nothing particular occurred. About this time Mr. Walker, from north of Scotland, and who was commonly called Commodore Walker arrived in the Bay, and formed an extensive establishment on Alston Point, on Northside of Bathurst harbour. Gentleman came attended by several young adherents – Mr married an Indian and now is dead – latter still living at 94. At Alston Point, Mr. Walker had a splendid and elegantly furnished summer residence; also five large stores, a requisite number of outhouses, and a tolerable strong battery. Had a fine lawn and handsome garden. At Youghall, near head of harbour, he had another large dwelling house, which he occupied in winter, besides a fishing establishment on the Big River – three miles from entrance. At this time Mr. Walker engrossed whole trade of Bay, then consisting of an extensive exportation of furs, moose skins, and hides, fat and tusks of walrus. To these general exports he usually added: – an annual cargo of salmon and sometimes two or three of cod and scale fish, to the West Indies and Mediterranean. … Gentleman continued to, by his example and influence, advance and improve the country, until his spirited and beneficial enterprize, was interrupted by war between Great Britain and her revolted colonies.Shortly after the commencement of this rupture, some of the revolutionary Privateers entered the Bay and wreaked their vengeance on Alston Point and all other settlements. Having taken and destroyed upwards of L10,000 worth of property here, they proceeded to Restigouche, where Walker had another establishment under name of Mr. Smith. After committing similar depredations there, Privateers were proceeding down Bay, when two English gunbrigs – Wolf and Diligence – intercepted them. An engagement took place off Roc Perce, near which, two of the American vessels were sunk, the rest having endeavoured to escape. After this affair, Walker returned to England, and was upon his representation of the state, condition and resources of the country, appointed to a subordinate command, under the Admiral on the North American station. When the expedition entrusted to his care was about to sail, it is said he died of apoplexy. First English settler in Gloucester.”

Excerpt from Pages 175 to 179

“… having passed Taboointac gully, on way to Miscou Point, the first rivers we meet in County of Gloucester are Great and Little Tracadie. The Great and Little Tracadie Rivers have a lake-like appearance – run through level country – rather sandy, but tolerably well wooded with red and white pine. … Pokemouche rises near the Anscout, a branch of the Great Tracadie – 30 miles long. … From this to Miscou – 30 miles – coast is dull and monotonous. Miscou Island forms southern entrance of Baie des Chaleurs. Island lies in deep water – 21 miles in circumference and is the first New Brunswick land, looked for by vessels, bound to any ports in Gloucester. Before capture of Quebec the French had an incorporated fishing establishment on Island. … Miscou Island is indented with creeks and gullies but … Mall Bay is only place of shelter for boats. Miscou contains quantity of birch, spruce and maple.”

From The History of Caraquet and Pokemouche by W. F. Ganong |

Excerpt from Pages 20 and 21

“… by the Treaty of Paris of 1763, all Canada passed from France to England, and the Acadian and Canadian French became British subjects, the more willingly because they were all justly and liberally treated by the British Government. The next year (1764) formal permission was given the Acadians by Royal proclamation to return and take up vacant lands in Acadia, and soon after, no doubt, began the permanent settlement of Caraquet. … March, 1769 – a permission from George Walker, magistrate at Nepisiguit, to Alexis Landry to settle at Caraquet, ‘in the same place which he had formerly occupied’; and other documents show that from September, 1768, until October, 1769, he was living at Caraquet and trading with Ross and Walker merchants of Nepisiguit.”

From New Brunswick – The Story of our Province by George MacBeath and Dorothy Chamberlain |

Excerpt from Page 135 and 136

“… The first permanent settlement on the Restigouche was started by Londoners, John Shoolbred and Son. They also had a post at what is now Bathurst. Another trader, Commodore George Walker, had arrived earlier. Walker was the kind of man who would do well in that rugged country. He had been Britain’s most daring commander of a fleet of privateers during the war. Then his fortunes had failed and he had come to Nova Scotia as an immigrant.”

Excerpt from Page 169

“… Outposts in Bay Chaleur area had suffered greatly from privateers during the war and from Indian raids afterwards. Both Walker and Shoolbred had practically been ruined; most of their settlers had left, except a few hardy settlers (Scots) like Robert Adams and John Duncan.”

From Landry, Alexis CB New Brunswick Museum |

“Alexis Landrie . . . Doit a Jean Blake

1 ? ? – 90th – ? £2″ 5″0

52 ” ” travaille – ? £1″10″4

1 paire de buttons a ” – ” 3″6

” d’Halifax £3″10″10

Vous aurez ? de payer a Monsieur Smith en ? Ordre le montant ? ? ? de lui livrer ? un ? ? ? a moi appertenant.

John Blake

? ?

? ?

Caraquette 15 Sept 1769

Pour ? , par son ? a payer le 28 d’Aout 1770 – Bonnaventure 13 August 1770

William Smith X

From The Innis-Rundle Manuscript Ganong Manuscript Collection |

Box 27, The History of Miramichi, Thought by Dr. Ganong to have been written by Robert Cooney”… to summer of 1784 inclusive was the arrival of many Scotch immigrants. … William Brown – was first who settled at Chatham. … John Blake who had been in the employ of Commodore Walker, in the Bay Chaleur.”

From Scenes From An Earlier Day by Louise Manny |

“… Commodore Walker – owned ship Charlotte (Taylor) came out on captained by Skinner – George Walker (Scotch gentleman) described as ‘late the Commander of a naval squadron’. Had an establishment at Bathurst – Nepisiguit (Alston Point) and Walker’s Brook – Trading posts. Alston Point was established 1766 and destroyed by American privateers 1776.”

From Bathurst, 1891 – 1951 by George Gilbert |

Excerpt from Pages 8 and 9

“… Another early settlement in Bathurst, which I have heard of was by a man known as Commodore Walker who established a fishing business on Alston Point … The story, as told to me by a very old man, was, that the Privateer carried away all his nets and fishing gear and then burnt his buildings. The charred foundations of some buildings, in a fairly regular row across the point, were pointed out to me as the remains of his business buildings.”

From The Heart of Gaspé by John Mason Clarke |

Excerpt from Pages 176 to 181

“… It was not until the fall of Quebec that capitalists from the Channel Islands became interested in this Gaspé fishing and among the first of these were members of the Robin family of Jersey. The Robins were established on Bay Chaleur in 1764, and probably on Cape Breton as early, doing business in the latter place under the firm name of Philip Robin and Co., and in the former at Paspebiac, as Charles Robin and Co., Philip and Charles being brothers. … When Robin arrived in Gaspé he found an establishment at Bonaventure controlled by Wm. Smith and with him entered into business relations, Smith gaining control of the stations up the Bay and Robin devoting his attention to acquiring or erecting new stations on the coast from Paspebiac down. Smith and Robin had a good many disagreements and finally ceased to cooperate. Robin’s enterprises were proving fortunate when the American war broke out and his serious troubles began. … Just about a year after, June 30, 1778, he writes to his brother Philip at Jersey an account of the capture of his vessels, the Bee and Hope, at the station at Paspebiac:’ On the 11th instant at about 11 o’clock at night, two American privateers schooners of 45 tons, two carriage guns, 12 swivels and 45 men each put alongside of the Bee and Hope and boarded them, there were but three men on board each, being all employed in the fishery and not expecting a visit from them so early, as otherwise the Bee could have kept them off had all the people been on board, she being the only vessel arrived for some time was unloaded in a week which obliged us to put her guns in her hole as she would not bear them on deck in so wild a Road without ballast and it could not be the case without we had determined to make no fishing ourselves, an object of Qtls. 2000 which I thought was worth our attention. The Hope had Qtls. 1400 fish on board, was to take Qtls. 200 more the next day and sail for Lisbon in a few days. They (the Privateers) sent her off the 13th and began to take everything out of the stores and ship them on board the Bee. She was rigged and was going off the 15th, after which departure the Americans came to our Habitation to take me away but I had fled to the woods the night before mistrusting it – however that morning three ships appearing, HM Ships Hunter and Viper, and Mr. Smith’s ship Bonaventure – the latter was here the first and fired at them, on their approach the Americans took in their Privateer all the dry goods they could come at and went away. I had concealed a little quantity (a third of the goods) which they could not come at – they had found the best part of our furs which they put on board, but having coiled the cable on them were obliged to leave them behind as well as the powder and ammo, which I did not expect, neither that they would leave the ship without setting her on fire, – both Privateers having been taken since at Restigouche so that I have recovered my goods to a trifle which they bartered with the Indians for canoes, for their escape. I am to pay 1/8 salvage on the Bee. The Hunter and Viper were laying in Gaspe but being informed by Capt. Fainton of Perce of the Privateer being here they set out – however they were too late to retake the Hope. Capt. John Boyle of HMS Hunter has promised to leave one of his ships in the Bay for our protection. The Bee is in ballast with 10 men constantly on board in the daytime who watch at night when there are 30 men on board and the shore gang is ready to join them in case of alarm. …’… before the season was over his apprehensions got the best of Robin and he returned to Jersey where he remained till summer of 1783.”

From Loyalists of Bay Chaleur by A. D. Flowers |

Excerpt from Page 2

“… Governor Murray, first of the military Governors of Canada, had received instructions as early as 1763 to begin the survey of lands in the province so that grants might be made to settle claims of dependants, but it was not until 1764 that the order was given for the survey at Gaspe Basin, and not until 1765 was the survey completed. Then, Townships along the coast were surveyed from Gaspe to the Restigouche for the next 25 years almost as fast as the Prayers of Petitions and others stated their claims.”Excerpt from pages 11 to 21″… Carleton returned to England, having been replaced near end June 1778 by Gen. Frederic Haldimand, former Governor of Three Rivers and more recently of Florida. … There were two Wm. Smiths, and the Smith at Perce was in no way connected to Trader Smith at Bonaventure, a representative of a London company and operator of the port at that place. There were other firms operating in the country, notably the Shoolbreds of London, expanding in the region of Nouvelle and Carleton, and the Jersey firm of John and Charles Robin who had a string of posts from Cape Breton to Pasbebiac. Much of the history of the coast during that period has been preserved by the letters and diaries of these traders, and especially those of Charles Robin which cover the early years until interrupted by the Rebellion. Carleton got away in time to escape the barrage of addresses, remonstrations, complaints and petitions from all sides, including the trading houses in England whose Canadian representatives were making such reports as that sent by Henry Shoolbred to John Shoolbred dated June 18, 1778, describing first an event that had taken place earlier that month:’ The Americans have already infested this country and at this moment there are two privateers up the bay – there were originally four, a brig, two schooners and a sloop came through the gut of Canso and have taken and destroyed all John Robin’s vessels and craft at Cape Breton … They seemed perfectly well acquainted with the situation at Paspebiac, Bonaventure and Nepisiguit (Bathurst). At Paspebiac they seized a brig loaded with fish, and took his pelts and himself confined in his house. They took the buckles off his shoes, and some they stripped of their shirts and did not leave them a sufficient supply of provisions (for trade or use). … these robbers burn what they cannot carry away … I have laid aside all thought of wintering in this country.P.S. – Bonaventure, July 1, 1778′ The foregoing is a copy of what I wrote you the 18th June from Perce, to which I refer you chiefly to inform you of the dangerous situation. One of the raiders mentioned mounted two carriage guns and 16 swivels and carried 30 men, the other had 10 swivels and 28 men. Their sails were bent and anchors-a-pick, only waiting for a breeze, when the Bonaventure appeared considerably ahead of the Hunter and Viper sloops-of-war. Journeau gave them 2 broadsides and obliged them to decamp with great precipitation, up-river, thinking to get into shoal water, but were over hauled and taken by Robin’s shaloops which engaged them for near an hour. They took to the woods and 10 of them only were taken, one of them dying of wounds. None were killed or wounded on our side. At Bonaventure, Mr. Roxbury began to remove the most valuable of our property in 2 shaloops, one with goods and the other with peltries. The latter were despatched to Restigouche and was taken by the privateers before the men-of-war got up, which they sunk when they took to the woods. The French inhabitants much favour the Americans and have also gained over the Indians by presents of flour, fur and goods out of our stores at Restigouche, but they watched our men conceal the goods and furs and told the privateers … The privateer vessels sail amazingly well, and row in a calm at five knots with 12 to 16 oars each. They are fought from the shelter of a hatchway with swivels and 40 to 42 men each. One is called the Lark, the other the Lively – … my shalloop David was seized, but was scuttled by her crew. I saved her after the Hunter and Viper took our shaloops as prizes’.Already the Shoolbreds and Smith were feeling the pinch and had united some of their enterprises to cut down competition and expenditures. Shoolbred would soon withdraw and in a few years would be followed by Smith and Robin. The sort of protection given by government ships was of doubtful value if they could await a capture, then seize the captured vessel as a prize of war … Cox had just returned from England, apparently at the urgent request of government, to take up the duties to which he had been appointed. Chief of these was defense of the coast. Charles Robin, who had bought back his schooner Bee from the navy, turned over care of his remaining goods to friends and left the coast September 23. But Wm. Smith sent in a report on October 3 as follows:’ We had fished until Sunday 27th elapsed, when four of our vessels, departing together were unexpectedly and in sight of their harbours, seized and taken by an American privateer, a schooner called Congress, Samuel Hobbs Commander – about 60 T. – with eight 3-pounders, 9 swivels and cannon. Seized were the ship Bee with a rich cargo of codoyl, peltries, and merchandise, Philip Fainton Capt.; the brig Otter with fishoyl and peltries; the brig Phoenix, John Norman with fish only; and the brig Fox, George Woodhouse, with cod, salmon, oyl, flour and staves’.On June 10, Robert Adams representing Shoolbred and Barclay, wrote from Bonaventure:’ Gentlemen – I have received yours of the 16th March … According to orders, I brought Le Coffel’s cargo here but by unhappy misfortune, the day after we were plundered by a rebel privateer of 10 swivels and 26 men. They took us on board and put us in irons while they plundered us of every article, except a few codfish. Except for the bad behavior of the inhabitants of this place they would have done us little harm. They loaded two schooners here, one they took belonging to Tracadaqueche, and the other to this place. The French settlers took more than the Americans. Re Le Coffel, I found he had embezzled a good part of the property … They plundered Mr. Murray’s stores at Tracadaqueche, and the savages came down from Restigouche and took all the goods belonging to Mr. Robin. We are now living amongst rebels on every hand …’