HIERLIHY YEARS

Chapter 4

We return to the Parish of Newcastle (Miramichi, New Brunswick) on September 11, 1787 to continue The Charlotte Taylor Story. This is a special and memorable day. Before James Horton Esq., Justice of the Quorum for Northumberland County, “in the said Parish of Newcastle in said county, Philip Hierlihy and Charlot Black (Charlotte Blake) were duly married … according to law.”

Charlotte Blake had been left a widow after the death of her husband John Blake Senior sometime before March of 1785. It is widely believed that she married William Wishart soon afterwards, but for reasons unknown, did not legally take his name. A child, William Wishart, was born of their union. This was during a chaotic period – the birth of the Province of New Brunswick (1784). The Miramichi River area had previously fallen under the auspices of the government of Nova Scotia. During the transition there were great difficulties particularly with respect to Land Grants. The lands granted by Nova Scotia Licenses had to be reapplied for and regranted in New Brunswick. This was a long and tedious process complicated by the assimilation of Loyalists, disbanded soldiers and other immigrants in the aftermath of the American Revolution. It was, understandably, a time of great conflict between ‘old’ and ‘new’ settlers and for a time there was tremendous animosity. ‘New settlers’ attempted to gain portions of the lands of ‘old settlers’. They viewed the original Nova Scotia Land Grants as overly generous and unfair. The legal affairs of that transitional time were complicated by the change in government bureaucracies. It took several years for the new order to become established and efficient. This may have affected or prevented the registration of marriages for a time in the affected areas. At any rate Charlotte used the last name of her husband John Blake when she married Philip Hierlihy.

Philip Hierlihy had been a Sergeant in the Prince of Wales American Regiment. After the American Revolutionary War the Regiment was disbanded and most members relocated to the Keswick area near Fredericton, New Brunswick, where they received Land Grants. Two disbanded soldiers of that unit bypassed the Keswick area and came directly to the Miramichi. One of them, Daniel Menton (Minton), had already arrived by 1785 and was marked on the Daniel Micheau Survey of that year. He was laying up logs to build a house on Lot 17 above the Widow Blake who was living with her family on Lot 8 in the Black Brook area. She was also marked for Lot 9. The other disbanded soldier of the Prince of Wales American Regiment was Philip Hierlihy. On September 11, 1787 ‘old settler’ Charlotte Blake married ‘new settler’ Philip Hierlihy. It was another in a series of unconventional moves that seemed to define her life.

That late summer of 1787 Charlotte had five children, and the youngest William Wishart, was just a baby. Her daughter Elizabeth Williams (or Williamson), by a man with whom she had fled England, was 12 years of age. She also had three young children from her marriage to Captain John Blake. The Blake children were John Junior, Robert and Jane (perhaps Mary Jane), and they were all under the age of 10. Charlotte’s household by the date of her marriage to Phillip Hierlihy was naturally a crowded and noisy place, filled with exuberant youngsters. Philip presumably moved into the Blake house on Lot 8 after their marriage. They would subsequently have five children together, putting a tremendous strain on their resources. The eldest son of Philip and Charlotte Hierlihy, Philip Hierlihy Junior died in Tabusintac, New Brunswick on the May 27, 1852. His obituary printed in the June 7, 1852 edition of The Gleaner stated that he was 63 years of age at his death. If this age is correct he was born between June 8, 1788 and June 7, 1789. In the 1851 Census of Alnwick Parish in Northumberland County he was enumerated as a 64 year old farmer and it was noted that he was sick at that time. If the age of 64 was correct then he would have been born around 1787. It is important to note that the Census data in those days was notoriously inaccurate.

Large families were the norm, and the Hierlihy household was little different than other burgeoning households of that time. The exponential population explosion after the American Revolution made it increasingly difficult for settlers to secure their firewood requirements. The harsh winters in the area demanded great quantities of this heating ‘fuel’ and year after year it became a depleted resource on their lots. There was limited marsh grass available for the sustenance of cattle in the heavily forested land. The fishery was in danger of failing due to lack of controls and greedy fishing practices. This combined to produce an increasingly acrimonious atmosphere as each family fought for a larger subsistence base. In the end, the Miramichi’s 200 acre or less Lots could not satisfy the demands placed upon them. After a time some settlers moved to ‘greener pastures’. In 1798 the Hierlihy family would settle further north on the Tabusintac River. But first they would have to survive the intervening ten years. It would not be easy.

While the growing family once again adapts to change and prepares for a difficult decade we will journey into the past of Philip Hierlihy so that we can understand him better. This very common surname Hierlihy is the anglicized form of two Gaelic names. Their ancestral territory was in County Clare and County Cork, Ireland. Dermot O’Hurley, archbishop of Cashel in the sixteenth century, was martyred when he refused to embrace the ‘Queen’s religion’. He was hideously tortured and hung from a tree outside Dublin, Ireland in 1584. The earliest race in Britain is thought to have been an Iberian type of small, dark-skinned people. They were followed by the Celts who were named Picts, or Painted People by the Romans. The Picts were a fair-skinned, red-haired race called Tuatha De Danaan by the people of Eire. The other branch of the Celts were Milesians., also a fair-skinned people with brown hair. Irish names of Milesian descent are ‘Herlihy, Hairlihy, and Hurlihy’.

Philip Hierlihy, son of Guilielmus ‘William’ Hierlihy and Marie ‘Mary’ Wall, was baptized 14 May 1749 as per the St. Mary’s Catholic Parish Register at Cork, Ireland. He later emigrated to Connecticut (see Imagery/Maps Map 1. Colonial Map of New England 1755). Timothy Hierlihy arrived in Middletown, Connecticut before Philip, around 1753, to seek his fortune. The exact relationship between Philip and Timothy, still unconfirmed, was discussed by Mrs. Robert Wishart (nee Janet Hierlihy) in a letter she wrote to Will and Evelyn on October 1, 1947. Having recently read an article about Timothy Hierlihy, founder of Antigonish, Nova Scotia, she concluded that Timothy was not the father of Philip Hierlihy, her great grandfather, as she had always assumed. She subsequently conjectured that they must have been brothers, for she knew they were closely related, with a strong family resemblance. However, she may have been mistaken, because Timothy’s father was said to have been Cornelius Hierlihy. If so, then Timothy and Philip were probably cousins. If, by chance, Cornelius and Guilielmus were one and the same, then Timothy and Philip could have been brothers. However, the Latin names imply ‘cousin-ality’, as Cornelius is sometimes nicknamed Neil or Lewis, and Guilielmus is definitely Latin for William. In those days Catholic Parish Registers were completed in Latin by the priests. Conversely, Cornelius may not have been a Roman Catholic.

Timothy was born in 1734, a descendant of the old ecclesiastical family, chiefs of which were hereditary stewards of St. Gobnait’s Church at Ballyvourney, Cork, Ireland. He probably found work as a clerk after his arrival in Middletown, Connecticut, for he had some education and good penmanship. His father was Cornelius Hierlihy, who had come to America as a Lieutenant in a British regiment and was killed in action in Canada. Two years after his arrival in Middletown, in 1755, Timothy Hierlihy married Elizabeth Wetmore at Christ Church. On his marriage there was perhaps a false presumption that he had left the Roman Catholic Church, the traditional faith of the Hierlihys in Ireland, and become an Anglican. His first child Timothy William was born soon after. The Seven Years’ War erupted and Timothy Hierlihy served throughout. He retired after the war with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in Middletown, Connecticut. He purchased land in Massachusetts which he rented, owned property in Florida, and had 70 acres on which he resided in Middletown. An Anglican communicant, he was a pew holder at Christ Church.

Halfway between Hartford and Old Saybrook, Middletown got its name in 1753. It was the wealthiest town in all of new England during the latter half of the eighteenth century. It’s wealth was derived from shipping and shipbuilding and it was a thriving port, doing trade with the West Indies and involved in the slave trade. Episcopal Churches were built throughout Connecticut to the displeasure of old Puritans who had inherited their hatred of the Church of England from their ancestors. Until the time of the American Revolution, although relations were frequently strained, Connecticut leaders pledged their allegiance to England. When their taxes were increased onerously in 1774 the Connecticut Assembly sent three delegates to the first Continental Congress in protest. The colonies stood at the brink of war. The Battle of Lexington and the ‘shot heard around the world’ touched off the break with England and Connecticut men who were pro-independence in their sentiments marched off to Boston. There was great conflict between neighbours as many in the colony continued to support the Crown. Mobs were assembled to persecute the loyalists in Connecticut and many were robbed, plundered, and made prisoners. The clergy, conspicuous in their fidelity to England, suffered and were persecuted for it. New Englanders felt that the authority of England and its National Church had to be crushed.

During the Revolutionary War Timothy Hierlihy became a Lieutenant Colonel in the Prince of Wales American Regiment. In 1778 he and his son Captain Timothy William Hierlihy raised an independent company for the Prince of Wales American Regiment and four other independent companies known collectively as Hierlihy’s Corps. These five companies were absorbed in 1782 into the Royal Nova Scotia Volunteers with Timothy Hierlihy as Lieutenant Colonel. They were ordered at that time to the Island of St. John’s – Prince Edward Island (see Imagery/Selected Topical Images – Shipwreck and Pioneer Cemeteries P.E.I.). After the American Revolution ended the Volunteers were disbanded in Nova Scotia and Lieutenant Colonel Timothy Hierlihy was retired at half pay. He got land in Antigonish, Nova Scotia and settled there with his family. His daughter, Mary, born in 1757 in Middletown, Connecticut, died just before the family’s arrival and was the first person buried in Antigonish. On October 17, 1784 Timothy Hierlihy sent a formal note to his son Captain Timothy William Hierlihy asking him to set out “Town Lotts” to encourage “Tradesmen and Maccanicks to settle amongst us, … lay out the said Lotts beginning with Lieutenant John Wheaton, Philip Hierlihy, and Jonathan Shepherd”. Philip, probably a cousin, was presumably expected to settle there also. Whether Philip Hierlihy ever stopped at Antigonish is unknown but he did not stay. He migrated to the Miramichi (New Brunswick) area where in 1787 he married Charlotte Blake of Black Brook. Tradition says that around 1797 Lieutenant Colonel Timothy Hierlihy, the founder of Antigonish Nova Scotia, died alone and neglected in his little house on Town Point.

Lieutenant Colonel Timothy Hierlihy remained in the Prince of Wales American Regiment until 1778 when he raised the independent companies known as Hierlihy’ Corps. Philip served throughout the American Revolution as a sergeant in the Prince of Wales American Regiment. It had been formed in 1777 and enlistments were continuously made to replace ‘non-effectives’ which numbered 216 at the time of the muster on November 15, 1779. The number of men enlisted before that date was 613 but of that total; 74 were dead, 19 were prisoners of rebels, 25 had taken discharge, 30 had been transferred and 113 were classified as deserters. Deserters were not only traitors who had joined the rebel side, that were also men who had retired without leave. In Connecticut and Rhode Island, where there was a stronger Loyal element than in the rest of New England, many men were recruited for the Queen’s Rangers, Prince of Wales American Regiment and the King’s American Regiment.

To encourage swift recruitment to the Loyalist corps the British government offered incentives. Loyal Americans, preferably wealthy and of significant social standing, were granted commissions if they were able to muster enough men for battalions. Their rank as officers was determined by the number of conscripts they brought into their companies. These recruits pledged to serve two years, or throughout the period of the war. Enlisted men received money and the promise of grants of land at the Peace. They were provided with the standard weapon of that time, the Long Land tower musket also known as the “Brown Bess’. The uniform of the Prince of Wales American Regiment was red trimmed with blue. Ten Companies of that Regiment, comprised of 33 officers, including chaplain and surgeons, and 442 men, were mustered in June of 1777 under Brigadier General Montfort Browne. He had served as Lieutenant Governor of Florida in 1768 and 1769, after which he became Governor of the Bahamas. Per Diem (daily) pay was £1 for Brigadier General, 17s for Lieutenant Colonel, 1s 9d for Cavalry Sergeants and 1s for Infantry Sergeants.

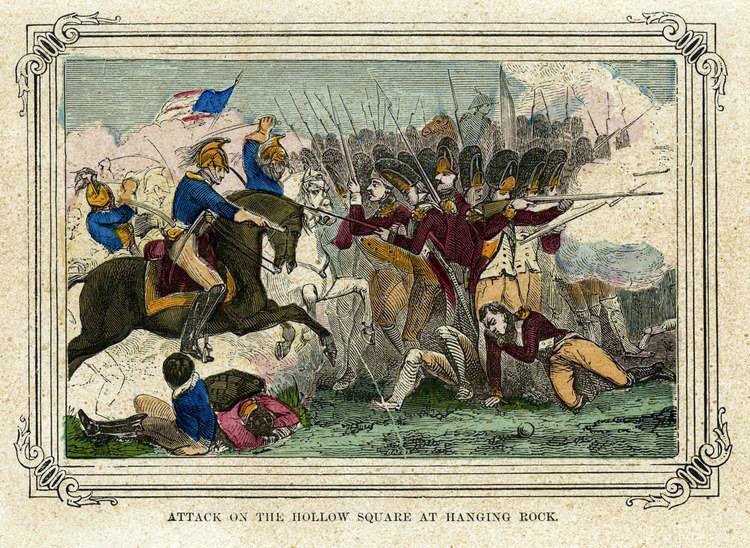

Throughout the course of the War years, the Loyalist corps operated along the New England coast. On August 29, 1778 the Prince of Wales American Regiment was part of the force that defeated the Rebels at the Battle of Rhode Island. The Regiment acquitted itself well in the Carolinas later in the War. In the four hour Battle at Hanging Rock, South Carolina, the Prince of Wales American Regiment was almost annihilated during the defeat of Colonel Sumter.

About half of all New Brunswick Loyalists were disbanded soldiers and members of their families. They were labeled ‘provincials’ to demarcate them from ‘civilian refugees’ although many fell under both categories. Almost all of them were evacuated from New York City and its environs to the mouth of the St. John River. They arrived in a wilderness area unprepared for their arrival. Many of them wintered in tents in the Carleton and Parrtown (Saint John, New Brunswick) area that first harsh winter. They were provided with standard government remuneration: food, seed, tools, clothing and supplies for three years. They were also given free land dependant on their rank in the service. Officers received pensions of half-pay. Soldiers were given the clothes on their backs and their weapons. The Prince of Wales American Regiment received their land grants, for the most part, on the Saint John River below the mouth of Keswick in the parish of Douglas (York County, New Brunswick). Lieutenant Colonel Gabriel De Veber eventually became Sheriff of Sunbury County. Lieutenant Monson Hoyt participated in the planning and laying out of the capital city of Fredericton. He later conducted business with General Benedict Arnold in the city of Saint John. Captain Daniel Lyman became one of the first members for York County in the House of Assembly. Agents or Senior Officers of Regiments were required in each province to take a roll of the state of their battalions so that the disbanded men could receive their entitled land Grants. It was to include names of members, their families, and their place of residence. However by January of 1785 the Regiments were so fragmented that the rolls were never completed.

Philip Hierlihy was included on the list of New Brunswick Loyalists. It gave his former home as Connecticut, his former rank as Sergeant and his first land grant as Miramich, New Brunswick. It is unknown whether he ever owned land in Middletown, Connecticut as had Timothy. The losses of property and effects in Massachusetts, Florida and Connecticut must have been severe for Timothy Hierlihy. One can only imagine that terrible day of his arrival in Antigonish, Nova Scotia when he buried his daughter and began the process of starting over. After years of war Timothy and Philip Hierlihy had been forced to leave “the wealthiest town in all of New England”, and to begin again in a northern, unsettled wilderness.

And so we return to the Black Brook area of the Miramichi River. Charlotte and Philip Hierlihy, newly married, have set up housekeeping together for a time at least in the Blake house on Lot 8 south side. Lot 9, beside them, lay undeveloped and marked for the Widow Blake. It had been part of the 1777 original Nova Scotia Land Grant of Charlotte’s deceased husband Captain John Blake. The final settlement of Lots 8 and 9, part of the contested estate of Captain Blake,would not be settled until March 4, 1798.

On August 1st, a month before his September 11, 1787 marriage to Charlotte Blake, Philip Hierlihy and Patrick Barry petitioned for Lot 70 north side. They were unsuccessful. On September 5th of that same year Duncan Robertson asked for Lot 5 south side, stating that he had lived in the Miramichi area for the previous twelve months. In 1791 this same Duncan Robertson and Elizabeth Williams, Charlotte’s eldest child, would marry. In January of 1788 both Charlotte and Philip Hierlihy were busy writing Memorials or Petitions. On January 6th, Philip again applied to Governor Carleton for Lot 70 northside and reiterated that he had applied the previous summer. Charlotte penned her January 7, 1788 Memorial the very next day to Jonathan O Dell (see Imagery/Selected Topical Images, Honorable Jonathan O dell) concerning her dispute over lot 53 south side. This document, in which we hear her speak for the first time, witness her style of writing, and observe her signature, is a priceless document. She signed it as Charlotte Blake although she had been Charlotte Hierlihy for almost four months. Presumably she did this because she had ‘purchased’ the land when her last name was Blake. She stated forcefully that “You have Desired me to Send a Certificate of what Cleared Land was on No. 53 South side of the River but the man will not sign it for me … he means to try to get located for it himself after he selling of it and Giving a Deed which Sir you have in your Office … I hope you will see me Justified in this Affair and have me Registrate for said Lot as it seems to me that he have a mind to try cut me out of it after I buying of and paying for it”. A note by an unidentified author was added to her Petition. It mentioned that she had married Philip Hurlehay, and that the Lot was sold to her by Jn. Humphries. He did not appear to have had any title to the Lot, either by improvements or by Register in Council. The tone of her Petition was blunt and direct. She capitalized the words she wished to emphasize, as was customary in those days. Most of her capital letters, particularly in her signature, were large and flowery as if she had spent time practicing and perfecting them. Interestingly the July 7, 1790 Memorial of Phillip Hierlihy, requesting meadow land at Bay du Vin, appears to have been written by the same hand. If that is the case then most probably Charlotte , but perhaps Philip, wrote them both. Years later the September 20, 1798 Memorial of Philip Hairlihy, in which he requested lands at Tabusintac, New Brunswick, was written with a very different style.

On April 28, 1788 Charles Stewart petitioned for lot 27 south side. His first house had been destroyed; the result of his burning brush around it. He rebuilt, but did not reside in his house during the winter preceding his Petition. He was otherwise engaged in assisting his fellow settlers by working at a mill, grinding grain, being the only miller there. This was his explanation as to why he had not cleared or improved much of his land. Many people attested to the truth of his statements and supported his Petition, among them: Duncan McGraw, Duncan Robertson, Philip Hierlihy and Alex. Taylor, Sr. Around this time Philip and Charlotte Hierlihy’s first child Eleanor was born. There were now six of Charlotte’s children in the Hierlihy household at Black Brook, born of four fathers.

Post-Loyalist life on the Miramichi, that is, life after the arrival and settlement of the ‘provincial’ (military) and ‘civilian’ Loyalists, was becoming more settled and structured. The process of establishing a legal infrastructure began but there were many difficulties and inconsistencies. The first meeting of the Court of Quarter Sessions convened at Beaubair’s Point in Newcastle (Miramichi, New Brunswick) on September 15, 1789. The Justices of the Peace in attendance were: William Davidson, John Willson, Alexander Wishart, James Horton, Arthur Nicholson, Alexander Taylor and James Fraser. Their duty was to implement the ‘Peace and Sunday Acts’, of which there were twelve distinct Acts: 1) Against Profanity on Lord’s Day, 2) Regulating Juries, 3) Punishing Rogues and Vagabonds, 4) Appointing Town or Parish Officers, 5) Preventing Trespasses, 6) Laying Out and Repairing Roads, etc., 7) Appointing Commissioners and Surveyors, 8) Regulating Servants, 9) Preservation of Moose 10) License of Retailers of Spirituous Liquors, 11) Regulating Fisheries, 12) Regulating Fish and Lumber. The next day Court reconvened for the trial of King vs Robert Forsythe, Murdoch McLeod, Alex. McDonald, and William Sharpe. William Martin and his wife Mary Ann had complained that these four men had broken into their house during the night of February 10, 1788 and taken their daughter Jane Martin away. The men were acquitted by the Court when the prosecution failed to appear. On January 19, 1790 the Court of Sessions met again for King vs James Walsh and John Wilson. Philip Hierlihy was sworn to the Grand Jury. The two men were accused of entering the house of John and Elizabeth Stewart where they took hold of Elizabeth and beat a negro servant, Beckwith Smith, with sticks. They were fined 10s each.

Two sons were born to Charlotte and Philip Hierlihy between the years 1789 to 1791. They were named, in order, Philip and James William. Charlotte had her eighth baby at her breast. It was probably a time of improving and adding to the Hierlihy homestead. Duncan Robertson acted as an attorney for John Dewar in a land transaction on October 12, 1789. On March 12, 1790 Duncan McRaw, late of the Black Watch 42nd Regiment petitioned for 25 acres of marsh land. He stated that he had moved to the Miramichi area three years previously. It was certified by D. Campbell that Duncan McRaw had been his servant for six years and was an industrious and deserving young man.

The 42nd Royal Highland Regiment (Black Watch) was formed of companies that policed the Scottish Highlands. Highlanders had long lived in Clans ruled by Chiefs, and attacks and raids between Clans was common. The Black Watch derived its name from its colours of black, green and blue and from its duty to watch over the Scottish Highlands. In 1740 the independent companies were mustered into the 43rd, later called the 42nd Regiment. For years the recruits were able to serve locally, but in 1776 at the outbreak of the American Revolution they were sent to America. They were a distinctive unit in their native dress with their Gaelic speech. They left Scotland May 1, 1776 with the Fraser Highlanders and were attacked by Rebel privateers on the Atlantic ocean. The Oxford became separated from the other ships in the convoy and landed at Jamestown, Virginia, a Rebel stronghold. The men of the 42nd Regiment were offered land if they joined the rebel cause but they remained loyal to the King and were imprisoned. They rejoined their Regiment two years later, after their release. The other transports crossed safely to Staten Island. The Black Watch had many victories throughout the War. They captured White Plains and Brooklyn in 1776. In September, 1777 they won at Brandywine and Paoli, where they attacked with ‘bayonet alone’, and in October they were victorious at the Battle of Germantown. In 1780 they participated in the siege of Charleston, South Carolina until its surrender. They subsequently returned to New York and departed there in a convoy of ships to relieve General Cornwallis but he had surrendered before their arrival. The Black Watch returned to New York where they encamped for the rest of the war.

About 100 men of the 42nd Royal American Regiment who took their discharge at the end of the American Revolutionary War came to Nova Scotia, which at that time included New Brunswick. The discharge dates were from August 25 to December 24, 1783. The Black Watch was one of the last Regiments protecting the embarking Loyalists. It is felt that these men came directly to New Brunswick in October of 1783. Some were registered on 50′ by 100′ Lots at what is today the city of Saint John, New Brunswick. Among them were Duncan McCrae and Daniel Robertson on Pitt Street in Parrtown and William Munro in Carleton. The Highlanders cleared land, built log houses and got through their first severe winter. In June of 1784 fire destroyed Parrtown. Civilian loyalists wanted the land around Saint John and the Regiments were ordered from Carleton. The 42nd Regiment relocated to the Nashwaak River area. One of their officers, Lieutenant Dugald Campbell surveyed and planned their settlement at St. Mary’s. On the Nashwaak Duncan McRaw held Lots 17 and 18, William Munro had Lot 36, and Donald Robertson received Lots 104 and 105. Many were dissatisfied with their Lots and it was decided that they could dispose of them and apply for 200 acres each as Loyalists. Of their number, 19 moved to the Miramichi River and 11 went elsewhere. The disbanded soldiers of the Black Watch were the hardiest of the ‘new settlers’. They were able to spend weeks in the woods in the dead of winter, hunting game and sleeping in the snow.

It is believed that two of Charlotte’s daughters married men of the 42nd Highland Regiment. Her daughter Jane (perhaps Mary Jane Blake) married Duncan McRae, McRaw or McGraw. Elizabeth Williams married Duncan Robertson. The name Duncan McCrae or McRaw shows up on the discharge lists and as a grantee at Parrtown and on the Nashwaak. The spelling of this name always varied so is not a consideration. They were probably the same individual. There is no record for Duncan Robertson although Daniel Robertson and Donald Robertson were grantees at Parrtown and on the Nashwaak. Was the Duncan Robertson who married Elizabeth Williams the gentleman who acted as attourney for John Dewar on October 12, 1789? I think it is very likely that Charlotte’s daughters did indeed marry these two men. Duncan Robertson was granted Lot 5 and Duncan McCraw Lot 7 at Black Brook on March 4, 1798 where they had both been settled for some time. They were practically next door to Charlotte and Philip Hierlihy. Years later Elizabeth and Duncan Robertson followed Philip and Charlotte Hierlihy to the Tabusintac area where they settled in close proximity. A lot there was marked for Duncan McRae (McGraw or McRaw). It does not appear that Duncan and his wife Jane (perhaps Mary Jane) McRae ever settled in Tabusintac. They remained in Black Brook.

“Phillip Hierlihy of Miramichie” sent a request to Lieutenant Governor Thomas Carleton in his Memorial of July 7, 1790. In it he asked for a section of “a tract of vacant marsh between the lot laid out for David Goodfellow near Point au Car and Black River in Bay de Vin”. He described himself as a “disbanded Noncommissioned Officer of the (Late) Prince of Wales’s American Regiment”. He added that he had thirteen head of cattle and that he had lost three head last winter “for want of hay”. There were two notes on the Memorial. The first was by A.Wm. Nicholson who attested that Phillip Hierlihy was “a very industrious man” with “a handsome improvement” who did in fact own the number of cattle specified. The second note was written by G. S. (George Sproule) who had a survey ordered. He wrote that “Philip Hierlihoy sold a lot near Black River Miramichie for Hay for his stock”. For a time, before he eventually sold it, Philip Hierlihy owned and had Grant of 157 acres at Bay du Vin, New Brunswick. It appears, from the note of George Sproule in this Memorial, that Philip Hierlihy had purchased that land himself. It was not his original Grant entitlement from his service with the Prince of Wales American Regiment during the American Revolutionary War. On September 25, 1790 at the Court of General Sessions, Philip Hierlihy was appointed Assessor of Rates and Surveyor of Roads for Northumberland County Middle District south side. His neighbour, John Murdoch, was appointed Overseer of the Poor.

James Fraser, John Willson and Arthur Nicholson sent a Petition to Jonathan Odell on February 11, 1791. They informed him that the Julians and other Indians had complained of James Gordon and Alex. Gregg trespassing on their lands at the branch of the Little South West Miramichi River. The area claimed by Gordon and Gregg was “Interval land … Indian’s since time immemorial” where they had begun to raise corn and potatoes because “hunting has failed’. Alex. Gillis who had petitioned the year before for Lot 27 south side sent in another Memorial in March of 1791. Gillis emphasized that Charles Stewart had no title to, nor had made any improvements on Lot 27. He stated that he had obtained an order and took possession but was driven off with violence and was petitioning for Lot 24 “not wishing to further instrife”. That same month John Murdoch, in beautifully written 17th century handwriting, petitioned for vacant land on the south side of the Miramichi River near Duncan Robertson. He planned to build a farmhouse on the land.

Philip Hierlihy, Duncan Robertson and others were sworn to the Grand Jury on September 20, 1791. The Court found James Rogers to be the father of the “bastard child” of Mary Edwards. He was ordered to pay for the upkeep of the child in order to prevent any expense to the Parish. That same day Hans Christian was charged with assaulting Benjamin Stymiest The Grand Jury was informed that Hans Christian, with force and arms, bruised and badly hurt Stymiest at Bay du Vin. He was bound over to the next Court of Sessions for £5. Afterwards, Philip Hierlihy complained to the Court that he “was overrated and prayed justice would be done”. He was given a discount of five farthings off the County Rate. At this time he was still Surveyor of Roads and Assessor of Rates for his District. Debtors were kept in jail for indefinite periods and they usually outnumbered confined criminals. In 1791 an Act was passed whereby a debtor could swear he had no property of value, except clothes and the tools of his trade. He would then be freed unless the jailer received 5 shillings a week from the creditor.

On September 22, 1791 Elizabeth Williams, eldest child of Charlotte Hierlihy, married Duncan Robertson. The marriage was conducted by James Horton Esq., Justice of the Peace, at Bay du Vin, New Brunswick. The participants were both residents of the Parish of Newcastle in Northumberland County. Elizabeth had been born around 1775 and would have been just 16 years of age on her wedding day. Duncan Robertson is said to have been a disbanded soldier of the 42nd Regiment (Black Watch). In 1795 the Elections Act allowed land-owning women to vote. They were disenfranchised in 1843.

Two daughters were next born to Charlotte and Philip. Honour ‘Honoria’ in 1792, and Charlotte Mary Hierlihy in 1794. On August 2, 1796 the Court of General Sessions convened with the trial of “Dom Rex vs Philip Hierlihy”. Philip pleaded not guilty to the charges made by the defendant William Donald. Evidence was provided by Duncan McCraw. Philip was found guilty and fined 10s and costs. On August 4, 1796 before the Northumberland Sessions, James Horton Esquire, Justice of the Quorum for Northumberland County, documented that he had performed several marriages in prevous years. He certified to the Court that “on the Eleventh Day of September, One Thousand Seven Hundred and Eighty-Seven, in the Parish of Newcastle in said County, Philip Hierlihy and Charlot Black (Blake) of said Parish were duly married by me according to law”. He also certified that “on the 22nd day of Sept. in yr. of our lord 1791 in parish of Newcastle in said County, Duncan Robertson and Elizabeth Williams of said parish were duly married by me according to law. Bay Devin 22nd of Sept 1791”.

Robert Beck of Newcastle sold “Philip Hierlihy, cooper”, a tract of land on the north side of the Tabusintac River on July 25, 1797 for £15. Beck had been occupying it. If this is correct then an English settler had lived in the Tabusintac area before Philip Hierlihy settled there. Robert Beck had been one of those involved in the ‘kidnapping’ of the Indian Chiefs (see Selected Topical Images, Abbreviated Hervey Family Tree) from the Napan Bay area of the Miramichi River back in 1777. This was at the outset of the American Revolution when the settlers of that area were also under duress from American Privateers. It was said that Beck later became “wild and lived as an Indian”. At the end of December William Allen petitioned for land on the north side. He had been a resident of the Miramichi area for years and had been employed teaching children in the “dead seasons” of the year.

March 4, 1798 was a very significant day in the life of Charlotte Hierlihy and her family. Lots around the Black Brook area where she had resided since before 1777 were finally formally granted under the Seal of New Brunswick. Charlotte Hierlihy’s previous husband, Captain John Blake, had died around the time that the western part of Nova Scotia became New Brunswick in 1784. His estate was tied up for years as Charlotte attempted to assign a portion of the Blake acreage to her presumed second husband William Wishart. This did not occur as it was stated that it would have defrauded the heirs (children) of Captain John Blake. Charlotte subsequently married Philip Hierlihy in 1787 but was still unable to get the estate settled. The Land Grants at Black Brook on March 4, 1798 finally resolved the matter although not to everyone’s liking. Charlotte’s son, John Blake Junior, claimed years later in his February 19, 1812 Memorial to Martin Hunter, that his father’s 1777 Nova Scotia Land Grant had totaled 550 acres. He felt that the children of John Blake Senior had “been deprived of their right”. The Nova Scotia license for the land stated that John Blake Senior had received 350 acres. One of these figures is obviously incorrect or Captain John Blake’s acreage was increased after the original license was issued. His designation as the “first British settler on the ‘banks’ of the Miramichi” may have entitled him to more than he had been originally given. In March of 1798 three Lots of significance in this matter were granted. Lot 8 – 161 acres, the site where the original Blake house had been built, was granted to John Blake Junior. Lot 9 – 160 acres, was granted to Philip Hierlihy as his original New Brunswick Grant. This was his entitlement for his service in the Prince of Wales American Regiment during the American Revolution.. Lot 10 – 154 acres, was granted to Charlotte Hierlihy herself.

The Daniel Micheau Survey of 1785 (see Imagery/Maps/Map 3. Miramichi River Lots) had reduced the frontage of the Lots of ‘old settler’ Nova Scotia grantees. This may explain the reduced acreage. But without knowing for certain if the original 1777 Grant was 350 or 550 acres, it is impossible to determine what really happened. On the Micheau Survey the Widow Bake was clearly marked for Lots 8 and 9. It appears that Lot 9 granted to Philip Hierlihy, although he was entitled to receipt of it, had certainly at one time been Captain John Blake’s land. The Hierlihy’s left the Black Brook area to live at Tabusintac, New Brunswick soon after these grants were formalized. Many years later on September 18, 1811, Lot 9 was sold by the 5 heirs(children) of Philip Hierlihy. On April 6, 1812, Charlotte Hierlehy deeded Lot 10 to her son William Wishart. William Wishart Senior may have even lived on Lot 10 at one time. It seemed a fair disposition of the original property; a third for an heir of John Blake Senior, a third for the heir of William Wishart Senior, and a third for the heirs of Philip Hierlihy Senior. However, a widow was only entitled to one third of her husband’s property as her dower unless his will stipulated otherwise. This was probably why John Blake Junior felt that the heirs of Captain John Blake had been short-changed.

On March 6, 1798, two days after the New Brunswick Land Grants were formalized, the Court of General Sessions began their March Term. The trial of “Dom Rex vs Philip Hierlihy”, accused of assault and battery, commenced. He was released on his own recognizance until the next Term. At the August Term of the Court of Sessions, the trial of the “King vs Philip Hierlihy” resumed. The Defendant was brought to the bar, and the indictment for assault and battery was read. Hierlihy pleaded guilty and submitted to the mercy of the Court. He was fined £3, 10 shillings and costs.

“Phillip Hairlihy” in his September 20, 1798 Memorial to Lieutenant Governor Carleton prayed to his Excellency “to Allot a tract of Land on the southside of the River Tabischan-Tack (Tabusintac), commencing about two Miles from the Bay, of 200 acres each, to Phillip Hairlihy Senr, Phillip Hairlihy Junr, James Wm. Hairlihy, *John Blake, *Robt. Blake, and *William Wishart”. He noted that the names preceded by *s were his “3 Stepsons”. He also requested an additional 25 acres of salt marsh for each individual, “commencing on the part most convenient to said lots”. He explained that he had a “Large Family of Twelve to support and that the land they were residing on was insufficient for their needs, the “Fuel not sufficient for the consumption of one winter”. Philip Hierlihy’s statement that he had a family of twelve to support on September 20, 1798, confirms that all five Hierlihy children had been born previous to that date. However some of the girls had already married so he may not have been actually supporting them. The immediate family consisted of Philip and Charlotte and her ten children. Five of the ten children were his.

George Sproule, the Surveyor General, noted at the bottom of the Petition, “Fredericton 8th – Feby. 1803″, that the Tabusintac lands and marsh described were vacant. He stated that “Robert Blake had already taken his allotment on the North side of the River and improved it”. When George Sproule penned his note on February 8, 1803, it appeared that only Robert Blake had located on the Tabusintac River by that date. But it is widely believed that Charlotte and Philip Hierlihy moved there in 1798, and that Philip was the first English settler in that place. Sproule may have been using outdated information that had been the case several years before. Dr. W.F. Ganong received information from M.Gaudet, a resident of Ottawa who provided him with information on the early French settlers of the Tabusintac River area. Gaudet informed Ganong that the first English settlers in Tabusintac were Philip Hierlihy, Duncan Robertson, John McLeod and William Tobin in 1798. Possibly those four men went there for a short period ahead of their families to clear land and to begin construction of their dwellings. The Black Brook lands still belonged to Robertson and Hierlihy at this time and it probably made sense for their families to remain behind until things were somewhat set up for them.

On May 24, 1799 Benjamin Stymiest and J. B. Williston penned a Memorial. They stated that they had reached the age of maturity and had become co-partners in building a sawmill at Bay du Vin River. They asked for a survey of a tract of land below the rapids and upstream on both sides. On July 1, 1801, Duncan Robertson, Yeoman, sold his Black Brook Lot 5 south side “for £100 lawful money of Gr. Britain” to Angus Fraser. This land had been granted to him “under Great seal of N. B.”. This proves that by May of 1799 Duncan Robertson and family had departed Black Brook and were presumably relocated in Tabusintac. It supports the statements of M. Gaudet to Dr. Ganong. In March of 1802 the Court of Sessions convened. Appointments were made for the District of Tabusintac, among them: John Black (Blake) – Commissioner and Surveyor of Roads; Duncan Robertson – Assessor and Overseer of Roads: William Wishart – Constable. These appointments certainly prove that a settlement of the Tabusintac area was well underway in 1802. They also contradict the implication in the note of George Sproule in 1803 that Robert Blake was the only settler there on February 8th. The appointments may also inadvertently reveal something else. Philip Hierlihy, who historically had an appointment, did not receive one in 1802. He may have been deceased by that time.

In the March 1803 Term of the Court of Sessions, a Petition was presented by Joel Turner for the inhabitants of Tabusintac. It outlined problems between the Indians of the Tabusintac area and the English settlers and it was filed for consideration until the August 1803 Term. On July 2, 1803 Benjamin Stymiest Jr., Yeoman, of Bay du Vin, sold one half of the interest in his sawmill to F. McRae. A month later McRae mortgaged his share of the mill for the amount for which he was indebted to Benjamin Stymiest. Years later Charlotte and Philip Hierlihy’s daughter, Charlotte Mary Hierlihy, would marry this Benjamin Stymiest. The Court of Sessions convened for another Term on August 3, 1803. Petitions of the English inhabitants of Tabusintac, outlining their complaints with the Indians of that area, were presented. Both sides were heard from. The Court ordered that the Indians not be molested nor any trespass made upon the lands or water that had been granted them by government. The vacant lands above the licensed Indian lands were to be occupied and fished by Indians and English settlers in common. The Indians were ordered to prevent their dogs from killing the sheep or cattle of the English by tethering them. They were instructed that the owners would be held liable for any damages inflicted by their dogs. The Court reiterated that they wanted the Indians and English to live peacefully together. To this end it was ordered that the length of nets set in Tabusintac above Indian lands not extend more than “one third part on either side leaving one third middle clear”. This regulation was to be enforced for one year. On November 5, 1803 Duncan McRae, who had been settled 16 years on Lot 7 south side at Black Brook, petitioned for “hardwood land” on the Napan River saying he had “Burnt off all wood”. By this date he had been married for several years to Charlotte’s daughter, Jane (perhaps Mary Jane) Blake.

We have arrived at the end of The Hierlihy Years. It is 1804 and most of Charlotte’s family, according to the 1804 Dugald Campbell Plan (see Imagery/Maps/Map 7., Plan Lagoon/River – Tabusintsac), had settled around her in her new location in what became later known as Wishart Point in the Tabusintac area. I believe that Dugald Campbell had been with the 42nd Regiment (Black Watch). After the American Revolution some soldiers of this Regiment retired and came with the Loyalist wave to New Brunswick. They received Lots on the Nashwaak River, planned and laid out for them by one of their own, Lieutenant Dugald Campbell. Several of those disbanded soldiers, including the two said to have married Charlotte’s daughters, made their way to Tabusintac. It appears that Dugald Campbell planned their settlement in that area too.

In 1804 Charlotte was once again a widow, this time the Widow Hierlihy. She would never remarry although she would live another 37 years. The date of Philip Hierlihy’s death is unknown but he is said to have drowned, possibly at Oak Point in the Miramichi area. Drowning was a common cause of death in those days. People traveled almost exclusively on the waterways. In winter they used the rivers as roads and accidents usually happened in spring when the ice began to thin. Philip’s parents, Hierlihys of Cork, Ireland, were of the Roman Catholic faith. Philip Hierlihy is believed to be buried at Bartibog or in the Indian burial ground at Burnt Church. The latter is more likely. That was also the final resting place of his Roman Catholic Black Brook neighbour, George Murdoch.

Philip Hierlihy seemed to be the most temperamental of Charlotte’s four partners, but only because he lived on the Miramichi during a time when activities were recorded, especially within the newly-established Court of Quarter Sessions. We know more about him than his predecessors. Did Philip decide to leave the Black Brook area because his lands could no longer sustain his family? Or was he tired of the skirmishes that were a regular part of daily life there at that time? It was probably a bit of both. Philip and Charlotte Hierlihy led a caravan of extended family to a new beginning on the Tabusintac River. Charlotte would eventually live there on her own; on her own terms, but never alone. She would be surrounded by her ever-expanding family for the rest of her life. We will finish The Charlotte Taylor Story in the final installment, After Hierlihy – Chapter 5 (CT’s Story).