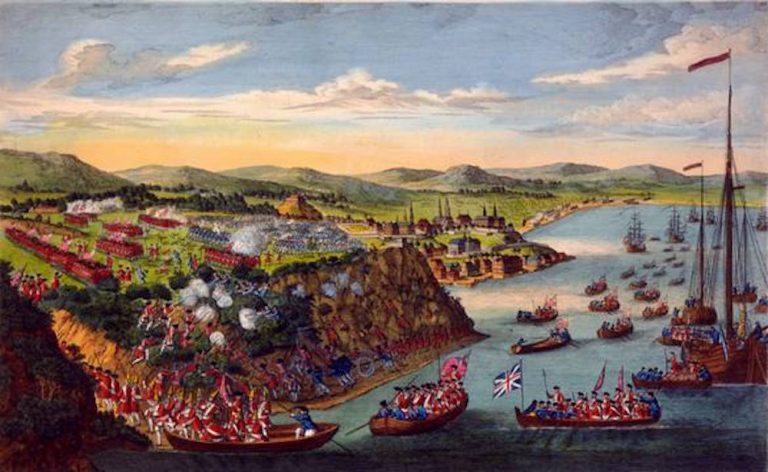

quebec

Quebec 1759

From Gaspé Land of History and Romance by Blodwen Davies |

Excerpt from Pages 100 and 101

“… It took the ships two days to weigh anchor and form the sea procession. Some hurried on ahead to chart the route, some to bar the river to the French ships which might be on their way up the St. Lawrence. It was difficult navigation all the way. There were no charts, no pilots, no lighthouses, no buoys. Their way lay by St. Paul’s Island, Bird Rocks, Cape Gaspé, Anticosti, Point de Monts, Bic and Tadoussac … For three perfect days they sailed on with practically every ship within sight of Saunders’ flagship. That must have been one of the proudest journeys in the annals of British seadogs. As far as he could spy with his long glass sailed the ships of his command, every sail bent to the breeze, flags flying, guns bristling. When all was well under way off Cape Gaspé, the Hunter was ordered to put back into the Bay to look about for any ships that might have had to drop out or were in difficulties of any kind. She found the Bay empty. The gulls circled screaming over the silent beaches and the ruins of Peninsule. The Hunter ran back along the length of the Forillon and signaled that all was well. From the Cape the ships took fresh bearings and veered into the Gulf … Wolfe took the opportunity while the Neptune rounded the Cape to write his will. On the table beside him lay the miniature of the lovely woman who loved him but would never be his wife … He sensed the fate that lay ahead of him. There would be no pleasant aftermath to the siege of Quebec.”

From James Wolfe – Man and Soldier by W. T. Waugh |

Excerpt from Pages 203 and 204

“… the Quebec expedition. Charles Saunders who was selected to command the fleet and promoted to rank of Vice-Admiral, was one of those officers who have a high reputation in the service and none outside. There was nothing showy about Saunders; as it never was his fortune to command a British fleet in a big battle. But he could be trusted to perform efficiently whatever task was given him to do. Saunders second-in-command was Rear-Admiral Philip Durell, who had done well at the siege of Louisbourg. Third in command was Rear-Admiral Charles Holmes. The fleet destined for Quebec was to be the largest on the seas that year. It consisted of 22 ships of the line and 27 smaller vessels, mounting in all 1944 guns … neither Wolfe nor Saunders could have achieved anything without the other. Once Quebec was reached it was Wolfe who was the agent and Saunders who was the instrument. Only as long as that relation was maintained could the siege prosper.”

Ships Involved

Pembroke | Centurion |

Devonshire | Squirrel |

Neptune | Prince of Orange |

Princess Amelia | Richmond |

Goodwill | Diana |

Sutherland | Trent |

Lowestoft | Racehorse |

Hunter | Vesuvius |

Seahorse | Porcupine |

From Wolfe by A. G. Bradley |

Excerpt from Pages 139 to 144

“… Actual strength of the force that sailed up the St. Lawrence with Wolfe, including marines and artillery, was just under 9,000 men. The three brigadiers were all good officers, Monckton and Murray in particular; Townshend had some talents and much bravery, but inclined somewhat to presume on his social rank and powerful connections … Admiral Durell with 10 ships had started for the St. Lawrence early in May to intercept any reinforcements or supplies from France. It was June 1st when Admiral Saunders, carrying Wolfe and his army, weighed anchor at Louisbourg … Among the French at Quebec there seems still to have been a feeling that the navigation of the St. Lawrence by a great English armament was almost impossible … On the 26th of June the whole fleet were safely anchored off the southern shore of the Isle of Orleans.”

Excerpt from Pages 158 and 159

“… he prepared to move 3,000 men of Murray’s and Townshend’s brigades across the channel dividing the Isle of Orleans from the north shore. A number of battleships were brought up as near the Beauport shore as shoals would let them come. Under fire of their guns and those of Port Orleans the troops, led by Wolfe, crossed without mishap the two miles of water that lay between the island and Falls of Montmorency. Montcalm’s left and Wolfe’s right were now within musket shot of each other; but between them yawned a great gulf, into which from a height of 250 feet plunged with one bound the strenuous torrent of the Montmorency … On the 21st he was again at Point Levi amid din of guns. On the 18th the Sutherland and some other British ships had done what the French declared impossible. Aided by a tremendous cannonade from Point Levi they had faced the fire of all the batteries of Quebec, and passed into the upper river, destroying what craft they found there.”

Excerpt from Pages 184 to 191

“… The British troops were now once more upon the river, some in frigates, some in sloops, others in flat-bottomed boats. All knew that the moment of action had arrived, but neither officer nor private knew its purport … Wolfe was busy in the cabin of the Sutherland penning his last orders to the troops … The leading boats had now drawn close to the Anse au Foulon … Keeping as near together as the darkness and the difficulty of the ascent would admit of, and dragging themselves up by help of bushes, the small detachment of light infantry and Highlanders were soon at the top … The last battalion of the 4,500 men, that Wolfe by his great and daring stroke led on to the Plains of Abraham, was winding its way, at daybreak, in single file up the face of the cliff that now bears his immortal name.”

Excerpt from Pages 210 and 211

“… The fleet now prepared to sail for England. It was the 18th of October, they had delayed longer than they intended, and the breath of autumn had reddened as with flame the vast sea of rolling forest over which at this season the eye may yet range with delight from the lofty heights of Quebec. The ramparts of the citadel and the battered wharves of the lower town were crowded with soldiers and spectators. The guns of the city were once more booming, but this time in solemn and measured fashion, unlike the angry uproar of war. A line-of-battle ship, with sails set and flags flying at half-mast, was gliding slowly down the river. Men and women, French and English, side by side, stood gazing at it with till with a favouring breeze it vanished seaward behind the woods of the Isle of Orleans. It was the Royal William, and on board of her, coffined and embalmed lay all that was mortal of the conqueror of Quebec. It was on 16th November that the Royal William cast anchor at Spithead. At seven o’clock next morning, amid the firing of minute guns from the fleet, the body was lowered into a twelve-oared barge, and at the head of a long procession of boats, towed slowly to shore. At Portsmouth it was placed in a hearse, and escorted through the town by the aides-de-camp, Captain’s Smith and Bell, in a mourning coach. The garrison with arms reversed, and large crowds of people, followed the coffin in slow procession through the streets. Muffled peals were rung from the church towers, and minute guns fired by the artillery. From Portsmouth Wolfe’s remains were carried to Greenwich, where they were placed beside his father’s in the family vault of the parish church.”

From Wolfe Portraiture and Genealogy by Quebec House Permanent Advisory Committee |

Excerpt from Page 108

“… September 13, 1759 – About 4:00 am James lands at Anse au Foulon with an advance party which scales the cliffs at Plains of Abraham and surprises French post at top. By sunrise main body of his troops is on Plains. Before the main action begins James is already twice wounded; when the French advance he takes post between Louisbourg Grenadiers and the 28th; just after British charge begins he is wounded again, is carried to rear and dies (age 32).

October 18, 1759 – Saunders sails for England with James’ body in the Royal William.

November 16, 1759 – Royal William arrives at Spithead.

November 19, 1759 – James’ body is taken to Blackheath

November 20, 1759 – Buried with father in St. Alfege, Greenwich.”

From With Wolfe to Quebec by Oliver Warner |

Excerpt from Pages 127 and 128

“… ‘The disposition of the ships under the command of Vice Admiral Saunders in North America, 5th September, 1759′,

Ship | Location and Duties |

Sutherland | In river, above Quebec |

Squirrel | “ |

Lowestoffe | “ |

Seahorse | “ |

Hunter Sloop | “ |

Stirling Castle | Off Point Levi |

Dublin | “ |

Shrewsbury | “ |

Alcide | “ |

Vanguard | “ |

Centurion | “ |

Captain | “ |

Medway | “ |

Pembroke | “ |

Trident | “ |

Richmond | “ |

Scorpion | “ |

Racehorse | “ |

Pelican | “ |

Vesuvius | “ |

Eurus | Isle of Camarasq |

Zephyr | In channel to the south of Isle au Coudre |

Baltimore | In channel to the south of Isle au Coudre |

Porcupine | Between Isle Orleans and North Shore |

Prince Frederick | Isle au Coudre |

Bedford | Isle au Coudre |

Hind | Isle of Bic |

Diana | Boston to convoy Mast Ships |

Lizard | Cruising between West Anticosti and South Shore |

Trent | Reconnoitre North Shore, Proceed along American Coast to South Carolina, Convey Trade to England |

Echo | Search North Shore, through Streights of Bel-Isle to Port of Labrador and Return |

Princess Amelia | At Isle Madame – * Admiral Durell Directed to Station Two of These Ships between Cape Torrent and East End Orleans |

Northumberland | “ |

Terrible | “ |

Devonshire | “ |

Orford | “ |

Royal William | “ |

Somerset | “ |

Prince of Orange | “ |

Neptune | “ |

Cormorant | “ |

Strombolo | “ |

Signed: Charles Saunders

From The Commonwealth of Nations by W. D. McDougall |

Excerpt from Page 176 and 177

“… each morning the English warships sailed several miles up the river past Quebec, with Montcalm’s soldiers hurrying on foot to keep up with them. When afternoon came the fleet sailed down the river. The French soldiers had plenty of exercise, while the English lolled comfortably on decks of the warships. Sometimes the ships would begin a furious bombardment with their cannon, and fearing an attack, the French army would be hurried to the threatened point. All this manoeuvering was planned by Wolfe and Admiral Saunders for the purpose of annoying the French to the point where they might come down from the high cliffs of Quebec to attack the fleet and army. Montcalm was too good a soldier to risk a battle with the well-trained British soldiers under Wolfe. To fight the French on even terms, Wolfe had to get his soldiers up the cliffs. This he succeeded in doing.”

From 78th Fraser Highlanders – The Second Highland Battalion of Foot |

“… June 2nd, 1758

As part of General Wolfe’s Army of 8,600 troops, the 78th Frasers led the attack, in a combined operation with the Royal Navy, on the French fort at Louisbourg. After a siege of two months the defenders capitulated. After this action the 78th Frasers were given the nickname ‘Les Savages Sans Culottes’ (Savages Without Pants)

September 13th, 1759

Seven hundred 78th Highlanders were among the 4,441 British troops that, in the pre-dawn darkness scaled the cliffs below Quebec. It was the French speaking officers of the 78th Frasers who deceived the French sentries.”

From General Wolfe by Edward Salmon |

Excerpt from Page 221

“… Admiral Saunders, for none but he could have taken so important a decision, arranged forthwith that the body of Wolfe should be embalmed and sent to England. It was his tribute, the most significant and eloquent he could pay, to the loss sustained by his country in the death of his military colleague; he and Wolfe for the past six months had lived and toiled together, discussed great strategic problems, evolved great schemes in the most trying circumstances, faced the fortunes of war in positions of joint responsibility, and to appreciate Wolfe’s quality both as man and as soldier none was better placed than the master of the co-operating fleet. Whilst the mortal remains of Wolfe were being encased for transference to his native land, those of his opponent found sepulchre in a cavity made beneath the floor of the Ursuline Convent by a British shell.”

From The Life and Letters of James Wolfe by Beckles Willson |

Excerpt from Pages 496 to 501

“… Let us return to the mortal remains of the conqueror. Hastily down the slope was the body borne to a place of safety. In the logbook of the Lowestoft there is this passage under date September 13: ‘At 11:00 was brought on board the corpse of General Wolfe’. After being embalmed it was transferred to the Royal William for passage to England.”

From Battle For A Continent by Gordon Donaldson |

Excerpt from Pages 198 to 200

“… On the morning of the 18th, Townshend and Saunders formally signed the surrender, and that evening 50 artillerymen entered the St. Louis Gate, pulling a gun-carriage bearing the British colours. The Louisbourg Grenadiers took post on the gates, while naval Captain Hugh Palliser landed in Lower Town, with a detachment of sailors. Townshend marched with his staff, and two companies of grenadiers to the Chateau St. Louis, Champlain’s fortress on the rock. A line of French troops was drawn up before the ruined walls and wrecked gun batteries. The commandant stepped forward to hand Townshend the keys to the fort. The white coats turned smartly to file away and grenadiers took their place. From the river below came the crash of a victory salvo by the guns of the fleet. It rocked even the three-decker Royal William, in whose stateroom lay the embalmed body of James Wolfe, awaiting the passage home. On November 17, the Royal William anchored off Spithead. A black funeral barge, escorted by 12 boats, brought Wolfe’s body into Portsmouth harbour. Bells tolled, guns fired in slow salute, one per minute, and the entire garrison lined the shore as the general was returned to the port he had called a hellish sink of vice. Behind the troops the ‘diabolical citizens of Portsmouth’ stood in silent respect. The body lay in state for three days at the Wolfe home in Blackheath, then was buried in the family vault at the parish church of St. Alfege, Greenwich.”