acadie/acadiA

Abbé Le Loutre

Jean-Louis Le Loutre was born on 26 September 1709 in Mortais, France, and died on 30 September 1772 in Nantes, France (63 years). His life history provides an example of how the interests of church (God) and state (Glory) can coalesce, in this instance to support French colonial ambitions in Acadia. Le Loutre inspired/conspired/intimidated both MicMacs and Acadians, to frustrate English ambitions for the region.

From Dictionary of Canadian Biography Dictionnaire biographique du Canada

(see http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/le_loutre_jean_louis_4E.html)

In 1730 he . . . entered the Séminaire du Saint-Esprit in Paris . . . when training completed transferred to the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères in March 1737 intending to serve the church in foreign parts. As soon as he had been ordained, he sailed for Acadia and in autumn of that year appeared at Louisbourg, Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) . . . Le Loutre spent months at Maligouèche . . . on Île Royale in order to learn the MicMac language.

. . . On 22 September 1738 Le Loutre left Île Royale for the Shubenacadie mission [Mission St.-Anne] . . . With the cooperation of the authorities at Louisbourg he immediately undertook to build chapels for the Indians.

Notes from Mary Lynn Smith:

- Louis XV of France declared war on England in January of 1744, and launched a massive seaborne invasion against England in February. A terrible Channel storm doomed the French invasion attempt.

- In North America Commandant Jean-Baptiste-Louis Le Prévost Du Quesnel at Louisbourg sent orders to Le Loutre in 1744 “that the Indians were to declare war against the English and that he must accompany them as chaplain in all their expeditions”, and they were particularly to block food supplies to the British from Acadian farmlands (Patterson, 33).

- In July of 1744, 300 Indians led by Abbé Le Loutre tried to overcome the English defenders of Annapolis Royal, without success.

- In August 1744 François Du Pont Duvivier led an attack on Annapolis Royal, with a combined force of Indians and French soldiers. Duvivier retreated after John Gorham arrived from New England with 60 Indian Rangers (John Gorham’s Rangers). Duvivier remarked in his journal on “the value of Le Loutre’s presence during the seige of Annapolis Royal.”

- In June of 1745, 4,000 New Englanders captured the French stronghold at Louisbourg, Île Royale, with Royal Navy support.

- Francis Parkman’s research determined that “Le Loutre arrived in Quebec on 14 September 1745, accompanied by five MicMacs, and left seven days later with specific instructions which in fact made him a military leader; henceforth, it was through him that the French government was able to exercise control over the Indians in Acadia. He was also to keep watch on communications between the Acadians and the British garrison at Annapolis Royal.”

- A follow-up French attack, led by Jean-Baptiste-Nicolas-Roch de Ramezay, was launched from Quebec in October 1746. After waiting for 23 days for naval support, de Ramezay, his 700 French soldiers, and Le Loutre left Annapolis Royal and returned to Beaubassin.

The French naval forces that were expected to help de Ramezay’s 1746 land attack never arrived at Annapolis Royal, given that France’s powerful armada (20 warships, 32 transports, 21 auxiliary vessels, 3,000 veteran troops, 10,000 sailors) had come face-to-face with disaster – shades of January 1744! After leaving France in June 1746 a terrible toll was exacted from the fleet by a combination of British naval action, storms, Sable Island shipwrecks, sickness, disease, and starvation. The fleet’s commander, the Duc d’Anville, died on 27 September 1746 at Chebucto [present-day Halifax]. Around 1,200-1,300 men died during the Atlantic crossing itself; over 3,000 were lost from the armada’s original complement. Many French soldiers and sailors were buried at different sites around Bedford Basin. The remnants of the Duc d’Anville’s squadron had to return to France, and Le Loutre took the opportunity to sail on the Sirène . . .

From Montcalm and Wolfe France and England in North America by Francis Parkman, Part 7, Chapter IV, 1884.

In consequence of “good service to religion and the state,” Le Loutre received a pension of eight hundred livres, as did also Maillard, his brother missionary on Cape Breton.

From Dictionary of Canadian Biography Dictionnaire biographique du Canada

(see http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/le_loutre_jean_louis_4E.html)

[Le Loutre] . . . “returned to Acadia in 1749 on the Chabanne, in company with Charles Des Herbiers de La Ralière, the new governor of Île Royale, which had been restored to France by the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle the previous year.”

From Montcalm and Wolfe France and England in North America by Francis Parkman, Part 7, Chapter IV, 1884.

With regard to the use of Indians Le Loutre revealed his thinking in a letter of 29 July 1749 to the Minister of the Marine in France: “As we cannot openly oppose the English ventures, I think we cannot do better than to incite the Indians to continue warring on the English. My plan is to persuade the Indians to send word to the English that they will not permit new settlements to be made in Acadia . . . I shall do my best to make it look to the English as if this plan comes from the Indians and that I have no part in it.”

From Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61 A Study in Political Interaction. By Stephen E. Patterson.

. . . they [the Council at Halifax] had received two letters reporting that Micmacs at Chignecto – with whom presumably Cornwallis had just signed a treaty – had attacked two vessels and that three Englishmen and seven Indians had been killed in the attack [August 1749]. When the council discussed the matter they concluded that this treachery was the work of another French priest, the Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre, who was then with the Indians at Chignecto, “and it is highly probable that he is there on purpose to excite them to war.”

. . . When on 30 September a Micmac raiding party killed four unarmed men working at a saw mill near Halifax harbour, and carried away another as a prisoner, British officials angrily took action . . .

. . . governor and council issued a proclamation [1-2 October 1749] ordering British subjects to “annoy, destroy, take or destroy the savage commonly called Micmacks wherever they are found” and offering a reward for every Indian taken alive or killed “to be paid upon producing such savage taken or his scalp (as is the custom of America)” (Patterson, 31).

From Montcalm and Wolfe France and England in North America by Francis Parkman, Part 7, Chapter IV, 1884.

. . . Jonquière, the Governor of New France, wrote to the Minister [9 Oct. 1749]: “It will be the missionaries who will manage all of the negotiation, and direct the movement of the savages, who are in excellent hands, as the Reverend Father Germain and Monsieur l’Abbé Le Loutre are very capable of making the most of them, and using them to the greatest advantage for our interests. They will manage their intrigue in such a way as not to appear in it.”

Notes from Mary Lynn Smith:

- The Dictionary of Canadian Biography explains that . . . The attacks made by the Indians led Edward Cornwallis, the Governor of Nova Scotia, to swear he would have Le Loutre’s head, and to describe him in October 1749 as “a good for nothing scoundrel as ever lived.” Cornwallis tried to capture him dead or alive by promising a reward of £50.

- During ‘Le Loutre’s War’ (1749-1755) frequent atttacks on the English were conducted by individual MicMac raiding parties, and by combined-force MicMac/Acadian raiding parties. These strikes inflicted injury on the English in different ways. For example: (1) a MicMac raid at Canso on 19 August 1749 saw an English vessel and 20 prisoners taken. The ship and its crew were transported to Louisbourg as hostages (later freed). Patterson observed on page 53 of his Study that Acadians and Indians were “especially effective in capturing small British vessels that ventured near or through the Cabot Strait, from which escapades the Indians brought back scalps to collect French reward money”, (2) unwary British settlers and soldiers were commonly ambushed, killed, and scalped when passing along roads or venturing into the woods for firewood, and (3.) a raid on Dartmouth on 13 May 1751 resulted in loss of life and property for the English. This combined-force raid, led by the Acadian Joseph Broussard, resulted in 20 deaths. Other English settlers were taken prisoner.

- Parkman described an incident that took place on 4 October 1750. He related that Captain Edward Howe was shot (purportedly by MicMacs) on the banks of the Missaguash River, after negotiations under a flag of truce . . . [Parkman concluded that] Le Loutre must bear a certain responsibility for the murder as the admitted agent of French policy, which sought constantly to identify in the minds of the Indians the interests of Catholicism and those of the state. The killing was an open act of hostility on the part of the MicMacs against the Protestant authorities in Halifax . . .

- All sides in this difficult and violent battle for North American empire were hardly models of virtue. Payment for scalps was a part of the irregular frontier warfare practiced in North America, with both the French and the English making such payments. The Halifax Military Heritage Preservation Society (HMHPS, Historical Paper No. 1, Edward Cornwallis, 12) notes that “With the arrival of Europeans, Indian scalping trophies were soon transformed into ‘a commodity to be exchanged for cash or merchandise and anyone – Indian, French, or English – was eligible to scalp or be scalped.” Prisoners were sometimes taken, especially if they could be ransomed off, or used in prisoner exchanges.

- Le Loutre was the French paymaster in Acadia. Parkman shared what the Intendant at Louisbourg, Prévost, wrote in August 1753, that “Last month the savages took eighteen English scalps, and Monsieur Le Loutre was obliged to pay them eighteen hundred livres, Acadian money, which I have reimbursed him.”

From Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61 A Study in Political Interaction. By Stephen E. Patterson.

“. . . the British arrived in numbers in 1749. At this stage the French asserted their claim to the present New Brunswick by building a small earthenworks fort at Beauséjour on the Isthmus of Chignecto . . . the French decided to make Beauséjour much more than a frontier outpost; they saw in it the opportunity to build a new Acadia by attracting to the lands they claimed the approximately 8,000 Acadians who lived in coastal settlements around Minas Basin, near the mouth of the Annapolis River or in various other places within Nova Scotia. If Acadians could be persuaded to move north of the Bay of Fundy or to Île St. Jean, they could build a self-sufficient society and strengthen French claims. Le Loutre took credit for the idea, and it was he, with full official sanction, who attempted to implement it.”

From Montcalm and Wolfe France and England in North America by Francis Parkman, Part 7, Chapter IV, 1884.

During all this time, constant efforts were made to stimulate Acadian emigration to French territory, and thus to strengthen the French frontier. In this work the chief agent was Le Loutre. “This priest,” says a French writer of the time, “urged the people of Les Mines, Port Royal [Annapolis], and other places, to come and join the French, and promised to all, in the name of the Governor, to settle and support them for three years, and even indemnify them for any losses they might incur; threatening if they did not do as he advised, to abandon them, deprive them of their priests, have their wives and children carried off, and their property laid waste by the Indians.”

From Encyclopédie du Patrimoine Culturel de l’Amerique Française http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org/fr/article-491/

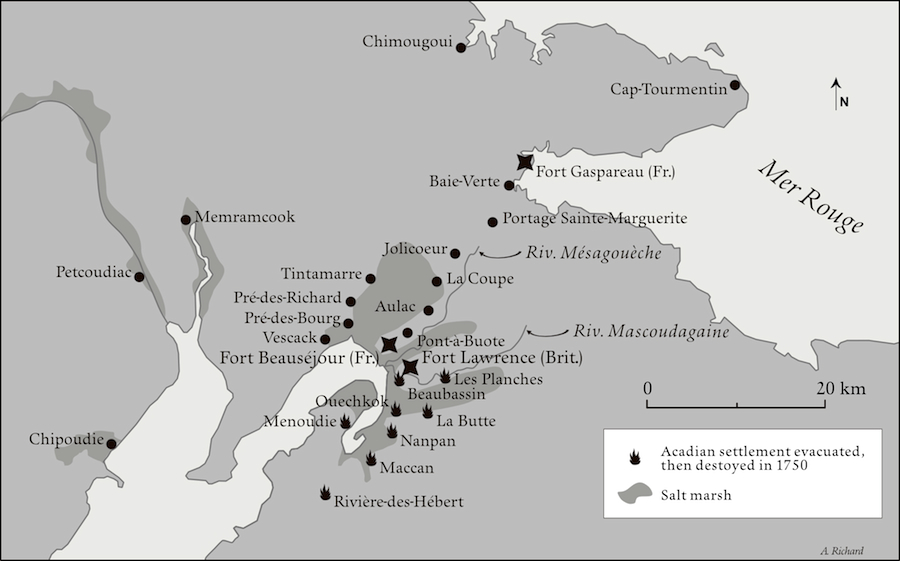

“In the spring of 1750, a British expedition was launched under the command of Major Charles Lawrence to drive the French out of the isthmus of Chignectou. Faced with a well-armed adversary, Lawrence and his troops had to turn back and temporarily accept the presence of these “intruders” on the territory they claimed. However, at the approach of the British troops, the French had given the order to burn down the village of Beaubassin by enjoining its inhabitants to pass on the west bank of the Mésagouèche river, in the territory considered to belong to New France . . . .”

From Montcalm and Wolfe France and England in North America by Francis Parkman, Part 7, Chapter IV, 1884.

“. . . towards the end of April, 1750, Major Lawrence landed at Beaubassin with four hundred men. News of their approach had come before them, and Le Loutre was here with his Micmacs, mixed with some Acadians whom he had persuaded or bullied to join him. Resolved that the people of Beaubassin should not live under English influence, he now with his own hand set fire to the parish church, while his red and white adherents burned the houses of the inhabitants, and thus compelled them to cross to the French side of the river. This was the first forcible removal of the Acadians . . .”

From Encyclopédie du Patrimoine Culturel de l’Amerique Française

http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org/fr/article-491/

In September 1750, Major Charles Lawrence commanded a new expedition which Beaubassin’s French troops could not resist this time, so that the British established themselves there as masters and erected a fort there called Fort Lawrence, opposite the fort French from Beauséjour. The French then ordered the burning of all the other villages located on British territory, east of Beaubassin, thus swelling the ranks of Acadian families already taking refuge on the west bank of the Mésagouèche river since the spring. To make matters worse, the whole crop was burnt in the barns and even if the inhabitants had made their cattle cross the other side of the river, they had no more fodder to feed them . . . Acadian refugees did not stop complaining to the French authorities who had forced them to leave their homes and their lands now on British territory, to which they urgently wished to return.

From Montcalm and Wolfe France and England in North America by Francis Parkman, Part 7, Chapter IV, 1884.

. . . some were eager to go; some went with reluctance; some would scarcely be persuaded to go at all. “They leave their homes with great regret,” reports the Governor of Isle St. Jean, speaking of the people of Cobequid, “and they began to move their luggage only when the savages compelled them.” These savages were the flock of Abbé Le Loutre, who was on the spot to direct the emigration. Two thousand Acadians are reported to have left the peninsula before the end of 1751, and many more followed within the next two years.

From Dictionary of Canadian Biography Dictionnaire biographique du Canada

(see http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/le_loutre_jean_louis_4E.html)

. . . As for the Acadians, the missionary [Le Loutre] thought that they were ready to abandon their land, and ever to take up arms against the British, rather than sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to King George II . . . On behalf of the French government Le Loutre promised to feed them for three years, and even to compensate them for their losses. They were not easily convinced and the missionary apparently used questionable means to force them to emigrate, threatening them, among other things, with reprisals from the Indians. The Acadians who moved, whether of their own free will or not, found themselves in an unenviable situation. Both on Île Saint-Jean and in the Fort Beauséjour region it was difficult to produce sufficient food to meet the needs of the new arrivals. The correspondence of Le Loutre, Des Herbiers, and La Jonquière, who was then governor of New France, makes daily mention of the supply problems in Acadia. In the spring of 1751 the missionary [Le Loutre] described the situation: the supply ships had not reached Baie Verte, consumption was greater than had been anticipated, the settlers were on the point of running out of meat and had received no wine whatever. Le Loutre was forced to divert certain presents intended for the Micmacs to the Acadians and the garrison at Fort Beauséjour. The situation on Île Saint-Jean was also desperate, and in the face of these problems the Acadians indicated their wish to return to their former lands . . . [Abbé Le Loutre] entrusted his Micmacs to Abbé Jean Manach, and crossed the Atlantic [arriving in France in December 1752].

From Montcalm and Wolfe France and England in North America by Francis Parkman, Part 7, Chapter IV, 1884.

“The fear is,” writes the Colonial Minister to the Governor of Louisbourg [Le Ministre au Comte de Raymond, 21 Juillet, 1752], “that their zeal [Maillard and Le Loutre’s] may carry them too far. Excite them to keep the Indians in our interests, but do not let them compromise us. Act always so as to make the English appear as aggressors.”

From Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61 A Study in Political Interaction. By Stephen E. Patterson.

. . . [After returning from France in April 1753, Le Loutre] . . . denounced Major Cope, his treaty [of 1752] and . . . had a special message for [Governor] Hopson, that “the English might build as many Forts as they pleased but he wou’d take care that they shou’d not come out of them, for he was resolved to torment them with his Indians and desired that the Governor might declare War Accordingly” (Patterson, 47).

Notes from Mary Lynn Smith:

- Fort Beauséjour capitulated to Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Monckton in June 1755. Le Loutre slipped away from the Fort and made his way first to Quebec, and then tried to reach France. The British captured his ship during his return voyage to Europe, on 15 September 1755, and Le Loutre spent the next eight years as a prisoner.

- Subsequent to his release, he died nine years later, in 1772, in Nantes, France.

- A French Catholic contemporary said of Le Loutre: “Nobody was more fit than he to carry discord and desolation into a country” (Parkman, Ch.4).

From Daniel F. Johnson’s Newspaper Vital Statistics

Vol 83 Number 1647 August 17 1892 Westmoreland Moncton, The Times

Special correspondent of Halifax ‘Herald’ – In a ramble around the old fort near Port Elgin (West. Co.) N.B. I found the military cemetery just outside of the moat and with the help of an old and very intelligent resident I was able to trace the inscriptions on seventeen of the headstones. It will be remembered that this fortification fell into the hands of the English in 1755. I will number the stones as you approach them from the entrance of the grounds: Headstone No. 1 – Here lies the body of Capt. Joseph WILSON? died Oct. 7th, 1755. Aged 50; No. 2 James WHITCOMB killed by the Indians July 24th, 1755 Age 23. There are indistinct letters before the name of this unfortunate young man who met his fate so sadly – probably they spelt ‘Lieut’. No. 3 is a fragment. The face of an angel is carved at the head and underneath is found the name of Nathaniel HODGES No. 4 a few years ago lay in the water just outside the bank. It was carefully removed by friends and placed within the sacred enclosure. The following inscription tells its own story. ‘Here lies the body of Sergeant McKAY who with eight men were killed and scalped by Indians in bringing in firewood, 1755?; No. 5 soft sandstone, inscription could not be deciphered No. 6 Moss covered, could not be deciphered No. 7 Give us a hint of New England puritanism, for on it we find the name of Mr. McCrease ROBERTSON died October 1755.

Abbé Pierre Maillard

From The Abbé Pierre Maillard: Treaty-making in Halifax, 1759-1762 by Leo J. Deveau. First published in the Halifax Chronicle-Herald, January 20, 2007 (Modified to address subsequent new research).

Abbé Maillard was born in 1710 in the diocese of Chartres, France; he died on 12 August 1762 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. After his death the Government of Nova Scotia honoured Maillard by giving him a full state funeral, with British, Mi’kmaq, and Acadians in attendance, and by providing a Halifax burial place in the cemetery of St. Paul’s Anglican Church (the Old Burying Grounds).

“Since his arrival at Fortress Louisbourg in 1735 at the age of 25, Maillard had walked his own labyrinth during his many years of missionary service – service that would outlive three popes, one British crown, and two French kings.

During that time, he had also been captured once by the British at the first siege of Fortress Louisbourg in 1745. He was sent to Boston, then deported back to France, only to arrive back on the Chebucto shore with the ill-fated Duc d’Anville fleet in 1746, a fleet that had lost ships and men due to storms and disease.

In late 1759, after 24 years of working as a missionary, and experiencing much hardship and witnessing too much bloodshed, Maillard was to enter the final chapter of his life and accepted Governor Lawrence’s invitation to come to Halifax and conduct peace treaty work for the British. The French called Maillard a traitor for his decision to assist the British. But Maillard’s decision to come to Halifax was in the service of the Mi’kmaq people he loved and had served.

The winter of 1759 was the worst ever on record. By the spring of 1760, New England Planters were starting to arrive in Nova Scotia to settle on lands previously farmed by the Acadians. In mid-October, Governor Charles Lawrence died. But throughout 1760 into ‘61 Maillard was able to ratify peace and friendship treaties between the British and Mi’kmaq chiefs – treaties that would endure into the 21st century, becoming the legal basis for many important Mi’kmaq land claims.

On June 25, 1761, many Mi’kmaq chiefs came to Halifax, from such areas as Merimichi, Jedicak, Pogmouch and Cape Breton to participate in a ‘Bury the Hatchet’ ceremony at the Lieutenant Governor’s farm in Halifax (near the present day Court House on Spring Garden Road). One Mi’kmaq Chief from Cape Breton described that; “As long as the Sun and Moon [the treaty] shall endure, as long as the Earth on which I dwell shall exist in the same State as you this day, with the Laws of your Government, faithful and obedient to the Crown.”

Acadian Expulsion

From The Federal Union by John D. Hick |

Excerpt from Page 141

“… Perhaps the most chronic area of contention between Great Britain and France … was Nova Scotia, a kind of buffer province along the seacoast between New England and New France where both nations had attempted settlements. By the Treaty of Utrecht, however, the French conceded ‘all Nova Scotia or Acadia’ to the British, but retained both Cape Breton Island and Prince Edward Island. To guard the Gulf of St. Lawrence and to serve as a trade centre, the French then built a strong fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton, while the British countered by founding Halifax in Nova Scotia and by encouraging immigrants to settle in the colony. At the beginning of the French and Indian war, French incitement of the Indians against the British led the latter in 1755 to expel about 6,000 French Acadians from their homes, and to distribute them along the seacoast from Massachusetts to South Carolina. Some of the exiles made new lives for themselves in the British colonies, others found their way back to Acadia, and still others fled to Louisiana. It was out of this episode in Anglo-French relations that Longfellow wove his fanciful tale, Evangeline.”

From The History of the Maritime Provinces by John Harper |

Excerpt from Page 2

“… Acadia, the Latin for the Micmac term A-cadie, was applied by the first settlers to the eastern part of New France, on account of its fertility. … Some derive it incorrectly from Laquoddie, a fish on the coasts. Cadie simply means a place.”

Excerpt from Pages 71 to 73

“… It became evident to Governor Lawrence at Halifax, that to maintain peace in Nova Scotia the Acadians must be expelled. When the troops from Boston arrived in the Bay of Fundy, one section … went to Fort Lawrence, under Colonel Monckton; another to Minas under Colonel Winslow. Major Handfield was in command at Annapolis. To these three, Governor Lawrence sent his instructions, revealing a plan for the removal of all Acadian families to the neighbouring colonies, and for the desolation of their homes. Winslow’s task was the bitterest. Those who lived around Cumberland and Annapolis were warned of the misfortune, and fled to the woods. Winslow, in a prepared speech, announced his orders. They were told that their lands, tenements, and livestock, being forfeited to Crown of England, they were about to be removed to other lands on the vessels which lay at anchor in the channel. A few who had kept back from the meeting escaped to the forest, to look and bemoan destruction which laid waste ‘those pleasant farms, of which naught now but tradition remains’. House, barns, hay and grain were consumed, and the cattle removed to English settlements. No wonder both men and women wept, when, from the decks of the ships that bore them to exile, they saw the smoke and ruin of many years’ toil. During the autumn the work of expulsion and demolition went on. Over 7,000 were removed from the little settlements scattered over the province. 1,000 sent to Boston; 500 to Pennsylvania. All over New England colonies the same hardships were endured, the same desire for return expressed. But Governor Lawrence, though he knew that many innocent suffered with the guilty, refused to allow them again a foot-hold in his province. A large number of them settled on the St. John and along bays and rivers of the Gulf Coast.”

Excerpt from Pages 80 and 81

“… The settlements on the Miramichi and Bay Chaleur were enlarged by the arrival of Acadians from Nova Scotia. The principal settlement on the Miramichi, at this time, was situated at the confluence of the two main branches of the river. At that point, a village of 200 houses had grown up under fostering care of Pierre Beaubair, who had also built a battery of 16 guns at French Fort Cove, farther down the river. For a time the place seems to have been prosperous; but a bad harvest in 1757, reduced the colony to a state of starvation. This was followed by a pestilence which swept of 800 of inhabitants, among whom was Beaubair himself. About a year afterwards news came that Louisbourg had been taken by the English. To destroy all these places, and to disperse or carry away their inhabitants, was a duty laid upon General Wolfe, before he prepared to pass with his three regiments to Quebec. It was an ignoble path towards a glorious fate. Suddenly but reluctantly was the task accomplished. Stores of fish and provisions were taken or destroyed. The people were driven to the woods, and the torch applied to their dwellings. As Wolfe, in his report, said, they did a great deal of mischief, spread the terror of the King’s arms, but added nothing to their reputation. After siege of Beausejour, the French retreated to the St. John River, where, under the supervision of Boishebert, they repaired the fort at the mouth of the river, and established themselves on farms as far as St. Ann’s (Fredericton). Their presence, so near, was full of danger to Nova Scotia; and what Wolfe did with the settlements on the Bay Chaleur, Colonel Monckton was ordered to do on the Bay of Fundy.”

From Acadia Lives by Jeremy Schmidt |

“… tintamarre, the din making – music to celebrate the Feast of the Assumption. The most important day of the year for … Acadians of New Brunswick, it marks the ascent to heaven of Mary, their patron saint. … The Acadians’ past is dominated by one of history’s epic calamities, their expulsion from their Nova Scotia homes by the British in 1755 during the final struggle between Britain and France for dominion in North America. The act drove generations of Acadians into cultural hiding. Two centuries after the expulsion, a French name in New Brunswick, where many Acadians eventually settled, was a sign of poverty, backwardness, diffidence. It was not unusual for a family to change its name – from LeBlanc to White, for example – in the hope of escaping the burden of history. … What they remember more than anything else is the 1755 expulsion, immortalized in Longfellow’s epic poem, Evangeline. The British, anxious to rid themselves of these disloyal subjects who had refused to sign an oath of allegiance after their settlements on the Bay of Fundy had been ceded by France, ordered the division and dispersal of Acadian families. Men were shipped off to various American colonies, women and children afterward to separate destinations. Homes were burned and farms confiscated. It was not incidental that the British coveted the Acadians’ land – fertile tidal flats reclaimed from the sea by generations of farmers, using a unique method of dyke building. Many of the Acadians followed painful and circuitous routes to Louisiana; others were assimilated in places as far away as the Falkland Islands. Roughly half of the 8,000 who were ordered deported did not survive the ordeal. They perished at sea, victims of storms; died in British prisons; or succumbed to cold and starvation in the woods near their former homes. A few made good their escape in Canada, but none without hardship. Two members of one group, after two years of wandering, came to rest halfway up a long bay on New Brunswick’s east coast that was protected from British warships by shallow waters. Over the years, word filtered out to other exiles, and Acadians who had found nothing for themselves elsewhere came to settle there. Today, the peninsula has the largest concentration of Acadians … Near the town of Caraquet is Le Village Historique Acadien, a collection of 46 buildings – almost all restored originals – meant to show Acadian life as it was between 1780 and 1880. Here men in traditional clothing operate horse-drawn ploughs, women bake bread in outdoor ovens, and card, dye and spin wool sheared from sheep.”

From New Brunswick’s 200th Birthday – Acadians Feel They Have Little To Celebrate by Chris Morris |

” … The Acadians are the children of Evangeline, a people whose sorrowful history is rooted in their expulsion and the long struggle to regain a home. … When the British defeated the French colonists and secured what are now the Maritime provinces in 1710, they were put in the uncomfortable position of trying to govern a French majority with an English minority. Acadians refused to swear allegiance to the Crown. In 1755, British administrators solved the problem by expelling the Acadians, scattering them through North America and Europe. Families were separated and hundreds lost their lives in long sea voyages. The tragedy of the expulsion was poignantly caught by Longfellow who wrote Evangeline. Some escaped deportation, hiding in remote parts of New Brunswick. Others who were expelled gradually made their way back to begin rebuilding a life in what they have always regarded as their homeland. When they returned, they settled in northern and eastern New Brunswick (in isolated areas), far from the English Loyalists who dominated life in the province following their arrival from the United States in 1783.”

From Survival of Acadians Site Occupies Ancestral Land by Helmer Bierman |

“… Majority of Acadians originated in ‘Poitou’ – the part of France that lies south of Brittany. … The area of Memramcook – St. Joseph is unique in the history of New Brunswick and in the history of Acadia. It was not far from the waters of Shepody Bay that Reverend Camille Lefebvre established the first Acadian institution of higher learning – the College St. Joseph. This is the only area near the Bay of Fundy where the Acadians still occupy lands cultivated by their ancestor before expulsion of 1755, when the centuries-long struggle between England and France was four years from the last major battle between the adversaries on the North American continent. About 6,000 Acadians were deported to British colonies of New England … Later other families were shipped to various parts of the world, including the southern part of Louisiana. In 1764, the British government, which had earlier condoned murder and pillage as a means of eliminating French speaking people in North America, decided to allow some of the Acadians to return to the Atlantic area. Those returning should not congregate in large settlements, and since their lands had been given away to other immigrants, the returnees went into the wilderness (many to what is now the Acadian peninsula). … The Acadians who were basically farmers exploited the opportunity to break into the rich soil of the tidal marshlands along the Bay of Fundy. They raised some extraordinary earthen dykes along the shore to keep out high tides and drained land for agriculture.”

Note from Mary Lynn Smith: The British did not expel or deport Acadians to Louisiana, as Louisiana was not a British colony at the time of the Acadian expulsion. Acadian arrivals in Louisiana came later, e.g., many Acadians became very dissatisfied with life in France, and left there for Louisiana when the opportunity arose.

From Les Familles de Caraquet by Fidele Theriault |

Excerpt from Pages 7 and 8

“… The colonization of Caraquet in the 18th century was affected by small populations regrouping beside parents and friends near fresh water. This was the case of the colony of streams Isabelle, Petit-marais, and Petite-riviere. These three places are the three villages of Caraquet, where the French Bazagier said that there were there in 1760, 36 families containing 150 people. … Alexis Landry and his family established at Petite-riviere (Sainte-Anne-du-Bocage). With his six boys, his guards Pierre Thibodeau and Joseph Dugas, he formed the first ? of Acadian refugees in Caraquet.”

Excerpt from Page 38

“… Blanchard This family … established themselves at Port Royal, and one of their young sons, Rene, emigrated to Grand Pre. His son, Olivier, married around 1751 Catherine Admirault of the Petitcodiac. There was born the pioneer of Caraquet, Olivier Blanchard … The village of Blanchard was destroyed in the fall of 1758 by Major Scott, and Olivier went for refuge to the estuary of the Restigouche where some French provision ships arrived in 1759. He escaped again the English troops that destroyed the village of Petit-Rochelle in 1760, and took refuge at Nepisiquit with his family, where he was counted in the census of Pierre Calvet in the course of the summer of 1761. He could not however escape from the surprise raid of Captain MacKenzie in the fall of the same year … Olivier Blanchard and his family and more than 300 Acadiens were taken prisoner to Fort Cumberland. Here tradition says that he was deported back to France and came back to the Bay of Chaleurs in one of the ships of the (cie) Robin … Charles Robin began his commerce in Canada around 1767, and kept for his first years of operation a journal which is most interesting for the history of this period.”

Excerpt from Page 81

“… Chiasson Joseph, ancestor of Chiasson family of Caraquet. He was born at Beaubassin around 1733. He wed around 1755 AnneHache and went with his in-laws for refuge to P.E.I. In 1760 he is with his family at Restigouche. He returned to P.E.I. in 1762 and lived there until 1772 … he went next to Miscou with a group of P.E.I. Acadiens.”

Excerpt from Page 266

“… Landry Alexis Landry is one of the most important Acadian patriarchs in the history of Caraquet. … We find Alexis Landry and his family at Bonaventure in 1765. He went next for refuge to Isle of Miscou near the brook named for him ‘Landry Brook’. In 1769 he obtained written permission from George Walker of Nepisiguit to regain possession of his old establishment at Sainte-Anne-du-Bocage. Charles Robin notes in his journal, that the Landry family and Arsenault family moved from Miscou to Caraquet in spring of that year. All during this period … Alexis Landry traded with English merchants who were established there. … Moore and Finlay, Amesbury and Bard, Charles Robin, William Smith and George Walker. He bought of them different provisions, that he in return paid with fish and game (pelts). As well as being a merchant, Alexis Landry was a carpenter and directed the construction of ships at Caraquet. In 1775, he built the brig ‘George’, for the company of John Shoolbred of London, he delivered to Bonaventure August 18, 1776 to his agent, William Smith.”

Excerpt from Page 429

“… Sivret This family is originally from the Isle of Jersey. The ancestor, Georges Sivret, had been captain for the (cie) Robin before opening up a trade for his own.”

From Caraquet Man Retraced 645-Mile by Gale Robichaud |

“… As the American War of Independence ended and new Loyalist settlers came to what is now New Brunswick, the francophones of Caraquet banded together to secure title to their property and avoid a second expulsion. Frances Gionet was chosen to travel to Halifax to ensure the British colonial administration recognized their settlement on the Acadian Peninsula. He made the entire journey on foot, and the document he secured for 14,000 acres of land for 33 local families became later known as the Great Caraquet Land Grant.”

From Acadian World Congress Published by The Telegraph Journal |

The Petitpas Family contributed by Fidele Theriault

“… Father Pierre Maillard, the famous missionary of the Micmacs in Acadia, was a close friend of the Petitpas Junior family which had settled on Ile-Royale (Cape Breton). In 1760, he asked the governor of Nova Scotia to allow him to retain the services of the brothers Louis and Joseph Petitpas in Halifax. They were the sons of Claude Petitpas Junior and his second wife, Francoise Lavergne. They spoke Micmac fluently and often acted as interpreters. Father Maillard also recommended to the governor two other of their brothers, Jacques and Jean Petitpas, as expert dyke builders.”

The Cormier Family contributed by Fidele Theriault

“… The ancestor of the Memramcook Cormiers, Pierre, married to Anne Gaudet, was captured by the British in 1755 and imprisoned in Fort Cumberland (Beausejour). Tradition has it that Pierre escaped disguised as a woman. On the eve of the day when he and other Acadians were slated to be deported to Georgia, his sister brought food as well as female garments.”

The Robichaud Family contributed by Fidele Theriault

“… In 1755, aged 86, Prudent was put aboard the ship Pembroke and was deported to North Carolina. During the trip, the Acadians took over the ship and beached it in the Saint John harbour. From there they fled to Quebec. Prudent Robichaud died during that trek. … Prudent’s third son, Louis, was also a very prosperous merchant in Acadia. He was deported along with his family to the Massachusetts colony. During his exile, he was granted by the abbe Maillard, vicar general in Acadia, the privilege of baptizing new borns, receiving marriage consent and presiding at Acadian funerals in the absence of missionaries. He and his family found refuge in Quebec around 1775. Louis’ son Otho settled at Neguac and was one of the Acadian leaders in New Brunswick from the end of the 18th century until his death in 1824. He is the ancestor of the Robichauds of that community.”

The Arsenault Family contributed by Fidele Theriault

“… The Arsenaults of the Gaspe are descended from two sons of the pioneer in Acadia, Pierre and Charles Arsenault. They are to be found chiefly in Bonaventure and Carleton. A son of Pierre, Joseph Arsenault, was militia captain at Restigouche, in 1759. Because of his military position, he must have taken an active part in the last naval battle between France and Britain for the possession of Canada, in 1760, known as the Battle of Restigouche.”

The Boudreau Family contributed by Fidele Theriault

“… Joseph Boudreau, son of Anselme and of Marguerite Gaudet of Beaubassin, found refuge at Restigouche on Chaleur Bay where he married Jeanne Hache in 1761. He later lived during a few years on Miscou before settling in Caraquet. He died at Nipisiquit in 1797.”

The Allain Family contributed by Fidele Theriault

“… Louis Allain married Anne Leger in 1748, at Beaubassin and settled at Petitcodiac, New Brunswick. Fearing deportation, he sought refuge with his family at Miramichi which was under the protection of commander Charles de Boishebert. He later settled at Bouctouche, leaving his son Michel, who was married to Josette Savoie, at Neguac.”

The Bourdages Family

“… Raymond Bourdages, born in 1728, also came from France to Acadia as a surgeon-major with the French troops stationed in what is now southeastern New Brunswick. He married Esther LeBlanc, from Grand Pre, at the Saint John river settlement after the deportation. They settled at Bonaventure, in the Gaspe, where Raymond Bourdages built stores and two mills. His property was destroyed by American privateers during the War of Independance.”

The Goguen Family

“… The founder of the Goguen family in Acadia was Joseph Gueguen, born in Brittany in 1741. He came to Acadia in 1753 as a protégé of the abbe Manach. In 1755 he managed to reach Quebec where he studied at the seminary until 1758. Having returned to Acadia, he was imprisoned at Fort Cumberland where he married Anne Arsenault. Around 1767, Joseph became the leader of the first settlers of Cocagne in New Brunswick. His influence was felt from Richibucto Village to Barachois because he had a superior education and spoke English, Micmac and Latin.”

The Landry Family

“… It is generally believed that the first Landry families came to Acadia around 1645 and that they came from the area of La Chaussee, France. Several Landry families left Port-Royal to settle at Beausejour, including the family of Alexis Landry, born at Grand Pre in 1728. After the fall of Beausejour, where Alexis Landry had taken part in the defense of the fort against the British troops, he was freed to rejoin his family on the Cocagne river. In 1769 Alexis Landry settled at Caraquet where, for forty years, he led an active and successful economic, social and religious life. This is so evident that history has graciously dubbed him ‘The Patriarch’.”

The Bastarache Family

“… The ancestor of the Bastarache family in Acadia was Jean Bastarache. He was called ‘Le Basque’ because he came from the Basque country. His grandsons, Pierre and Michel, were deported to South Carolina during the fall of 1755. Along with a dozen other Acadians, they returned to Acadia by way of Quebec – a six months’ journey – to find their families. Michel Bastarache later settled in Tracadie where many descendants bear the surname Basque.”

The Savoie Family contributed by Fidele Theriault

“… The Acadian Savoie family is descended from only one pioneer, Francois Savoie who was born in France in 1621 … Only one of his sons, Germain, who had settled up river from Port-Royal and who had married Marie Breau, left descendants in Acadia. … The Savoies of New Brunswick are descended from Germain who fathered six sons, including Jean dit Iane, Jean-Baptiste dit Baptist and Joseph who all settled in Shipoudie (Hopewell) during the first half of the 18th century. Because of this move, the Savoies are among the oldest families in New Brunswick. According to a story noted by Placide Gaudet and published in the form of a letter to Le Moniteur Acadien, the Savoies were among 85 Acadians arrested by the British in August, 1755, and imprisoned at Fort Lawrence in Beaubassin. During the night of October 1 – 2, the Acadians escaped through a hole which they had dug under the walls of the fort. They joined their families in Petitcodiac where they placed themselves under the protection of commander Charles Deschamps sieur de Boishebert. During the summer of 1756 these families traveled to the Miramichi where the number of Acadian refugees was estimated at 3,500. The large families of these Acadian pioneers, belonging to Jean, Jean-Baptiste and Joseph Savoie quickly spread throughout the Miramichi and in the neighboring areas. At the beginning of 1800 their children or grandchildren were settled at Oak Point, in Tabusintac, Tracadie, Pokemouche, Lameque, Shippagan, Bouctouche, Eel River and even at Carleton in the Gaspe.”