health Threats

Introduction – Health Threats

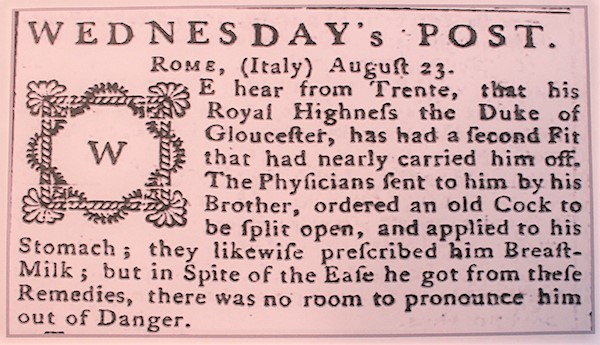

Settlers brought health knowledge and beliefs from native countries to their new homes. Remedies, though strange to 21st century people (see Wednesday’s Post above), were applied in the serious effort to save lives.

Further, visions of apocalypse based on biblical teachings could colour responses to health threats. New Testament prophecies described four horsemen being summoned, riding on white, red, black, and pale horses, to bring the end of time. Ezekiel warned in the Old Testament that punishments from God would descend in the form of sword, famine, wild beasts, and plague. These concepts undeniably contributed to an increased sense of apprehension amongst early Miramichi residents. Anxiety about life’s uncertainty, as old as humankind, emerged time and again when sickness appeared. Illnesses changed lives then, as now, with shock waves of variable intensity. For example, see Horace Walpole, outlined below:

From: The Letters of Horace Walpole (ed. by J. Wright) 1840. Pages 470 and 471

. . . The dangerous situation in which his Royal Highness the Duke of Gloucester has been, and out of which I doubt he is scarce yet emerged, though better, has added more thorns to my uneasy mind. The Duchess’s daughters are at Hampton Court, and partly under my care. In one word, my whole summer has been engrossed by duties, which has confined me at home, without indulging myself in a single pursuit to my taste . . . I often wish myself a monk at Cambridge . . .

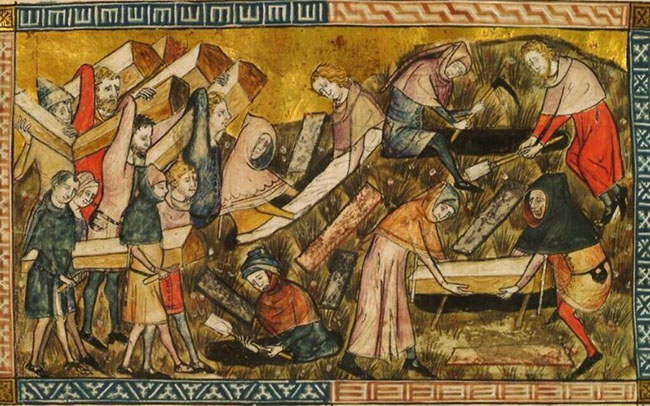

The Dark Ages – Plagues and Epidemics

From The Hamlyn History of Medicine by Roberto Margotla 1996. Reed International Books Ltd. London.

Excerpt from Page 63

Besides the Black Death (1347-49), dancing maria, St. Vitus’ dance, St. Anthony’s fire (ergotism), Sudor Anglicus (the English Sweating Sickness) and scrofula (king’s evil) were among the plagues that devastated Europe.

Yellow Fever

Yellow Fever is by definition an acute, infectious intestinal disease of tropical and semi-tropical regions, caused by a filterable virus transmitted by the bite of a mosquito (genus Aedus) and characterized by hemorrhages, jaundice, vomiting, and fatty degeneration of the liver: also called black vomit, vomito and yellow jack. After the bite of an infecting mosquito there is an incubation period of several days while the virus is multiplying in the body. Severe cases start characteristically with a sudden onset of fever, headache and pain in the abdomen, back and limbs. The infected person may hemorrhage and vomit blood, and because the virus injures and destroys liver cells, jaundice is common. The kidneys may start to produce blood and protein in the urine. Recovery can start at any stage and is remarkably complete, conferring lifelong immunity. However in a certain percentage of cases, there is relentless deterioration ending in death. There is no known practical way of eliminating the yellow fever virus from the vast tropical forests of Africa and South America, where monkeys are the hosts and mosquitoes are the carriers. Present day vaccination is available and effective for those travelling to the Tropics.

From Jamaica – The Old and the New by Mary Manning Carley

Excerpt from Page 32

“… The chief curse of Jamaica, yellow fever, which made the island a by-word for generations as a real ‘white man’s grave’, was introduced with the slave trade from Africa, but was at its most virulent during the 18th century.”

Excerpt from Page 81

“… Mosquitoes were for centuries an appalling menace to human health and were responsible for the terrible casualties in yellow fever epidemics.”

Excerpt from Page 155

“… Kingston … Famous regiments have been stationed here … Records of arrivals of Regiments of Foot in Jamaica exist in the old Jamaica Almanacks from 1780.”

Excerpt from Page 160

“… St. Andrews – The old court house and church are still there. The latter dates from 1700 … There are some ancient tombs in the churchyard, many to serving soldiers and sailors stricken down by that old scourge of Jamaica – yellow fever.”

From The Cradle of the Deep by Sir Frederick Treves

Excerpts from Pages 121 and 122

“. . . St. Lucia . . . A little way down the side of the Morna Fortune is the officers’ cemetery. The road leading to it, which was once so well worn, is now overgrown with grass. This ever silent gathering place of the British is the most beautiful spot on the side of the hill. A number of graves are blackened with age. Some are of stone, others of weather worn brick. Most of them tell the same story – the roll call of the Yellow Death, the major of this regiment or the lieutenant of that, and so many of them mere lads. The loss of life among the British troops in the West Indies and notably in St. Lucia, was in those days appalling. The majority of the deaths was due to yellow fever . . . . In 1780 – four newly raised regiments were ordered to Jamaica. They stopped on their way to St. Lucia, where they contracted yellow fever. By the time the transports reached Kingston Harbour they had lost 168 men by death, and had 780 on the sick list. During the course of the first five months, after the survivors had been stationed at Jamaica, 1100 more died of the fever and other diseases.”

Excerpt from Page 224

“. . . Circa 1598 – The pirate peer had hoped to make San Juan a base from which he could conduct an extensive and profitable buccaneering business in the adjacent districts. Unhappily for this purpose the fever fell upon his men, and killed them in such numbers that his force was soon reduced to half its strength. The right Honourable the Earl of Cumberland, M.A. Cambridge and pirate, feared nothing he could see, but this invisible horror filled him with a numbing dread. He saw the strong man dragged to the ground by unseen hands, his face become yellow as if from fear, his eyes glare from his head as if he beheld the vampire face to face, his fingers wandering to and fro as if in search of a clue, his voice toneless and inhuman, like the voice of a ghoul.”

Excerpt from Page 303

” … The most human building in Jamaica in the town of Port Royal is the old church . . . A tablet announces that it was rebuilt in the years 1725-1726. … The walls are covered with memorials and tablets of every type and period. They tell the ever-repeated story of men lost in gales or killed in action, of men who sank with their ships, and above all of the host who were sacrificed as a tribute to the Minotaur of yellow fever. How many thousands of British sailors and soldiers lie buried in the sands around Port Royal no chronicle can tell. Those whose names still linger on the walls of the ancient church are but a mere fraction of the multitude. The monuments are erected by widows, old shipmates, sisters and daughters.”

Excerpts from Pages 352 and 353

“… An attack upon Cartagena, Venezuela was made in 1741 by Admiral Vernon, otherwise known as ‘Old Grog’ or the ‘Hero of Porto Bello, Panama’ … One month after the fleet had appeared off the Boca Chica a force of 1500 men was landed to attack Fort San Lazar. The assault was made just before daybreak but affairs at headquarters were so mismanaged that the English were repulsed with 179 killed, 459 wounded and 16 taken prisoners. During the progress of these events yellow fever broke out in the fleet, with the result that no less than 500 men died, while over 1,000 were lying sick.”

Smallpox

From The Encyclopedia Canadiana Volume 9 – 1958

Excerpt from Page 334

Smallpox is a highly infectious disease, carrying a relatively high mortality and usually leaving permanent scarring of the features – pockmarks – on recovery. Caused by the variola virus . . . smallpox was introduced into Canada by the white man. Early accounts tell of the opening of the Hotel Dieu at Quebec in 1639 for the care of the many cases of smallpox. There were devastating epidemics among the Indians on the lower St. Lawrence, in Acadia, and in Maine in 1694. Severe epidemics occurred in New France in 1702-03 (3,000 died in Quebec alone), 1755, 1759, 1766, and 1783, when another 1,100 died in Quebec. Jenner’s cowpox vaccine was received from England by Colonel Landman at Quebec about 1801-02. At about the same time Dr. J.N. Bond of Yarmouth Nova Scotia vaccinated his infant son, and in Newfoundland Dr. John Clinch is said to have used it. In 1821 an Act was passed in Quebec granting 1,500 Pounds for the promotion of vaccination. The disease was frequently introduced by immigrants. Although once as common as measles and much more fatal, smallpox is now practically non-existent in Canada.

From The Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario, Canada), 4 June 1963, Tuesday, Page 32 |

During the terrible smallpox epidemic in the winter of 1800-01 he [Simeon Perkins] recorded the first use of Jenner’s ‘knee-pox’ in Canada. In his account of one of the first vaccinations he wrote:

“My wife, Lucy, Eliza, Eunice, Mary, Simeon and Charlotte are inoculated by Mr. John Kirk, all in the left hand between the thumb and the forefinger, not in the loose skin but in the hand, by making a small incision and laying an infected thread into it about three-eights of an inch in length. He then put a small square rag doubled, and over that a bandage to keep it in place.

My wife stood the operation very well. Some of the children were faint.”

From PANB Daniel F. Johnson’s Newspapers

Vol 36 No. 1432 Nov. 18, 1874 North Co.: Newcastle Union Advocate

A man named HACHE residing at Pokemouche (Glouc. Co.) died Saturday last. It appears that a brother of Hache’s died at Montreal sometime since and the latter, on being apprised of the fact, proceeded thither, and bought home trunks containing the clothing and other property of the deceased. On his way home he was taken sick and soon after his arrival died. There was no physician present, but from a description of the symptoms given by a neighbour of HACHE, who applied for advice and medicine at the Lazaretto, there is little room in doubt that the disease was smallpox. Since the above, we learn that the widow HACHE is now sick with smallpox.

Leprosy

From: The Hamlyn History of Medicine by Roberto Margotla 1996. Reed International Books Ltd. London.

” . . . As the imagined aides of the devil, who was assumed to be the cause of the plague, Jews and lepers became scapegoats. Thus in many parts of Europe, but especially Switzerland and Alsace, Jews were massacred together with those lepers who had escaped the plague.

Just as the word plague was used as a generic term for any epidemic, so in the Middle Ages leprosy was the name given to many skin diseases, doubtless including non-infectious conditions such as eczema and psoriasis, as well as diseases like smallpox . . . Leprosy is in fact contagious, but it is spread only with difficulty. It seems that in Britain true leprosy died out completely by the 15th century . . . “

From PANB Daniel F. Johnson’s Newspapers

Vol 23 No. 1181, April 18, 1865 Saint John, Saint John: Morning Telegraph

d. Tracadie (Glouc. Co.) Tuesday morn., 11th inst., age 31, James NICHOLSON, M.D., medical attendant at Lazaretto. His remains were removed to his father’s residence, Chatham (North. Co.) and thence conveyed yesterday for interment to ST. Andrews burying ground. – ‘Gleaner.’

Note by Mary Lynn Smith: Cause of death was tuberculosis.

Vol 25 No. 1445 Dec. 10, 1867 Saint John, Saint John: The Morning Freedom

Death of REV. F. X. LAFRANCE at Barachois, Tuesday, 26th ult., when P.P. of Caraquet (Glouc. Co.) he built the Lazaretto for the wretched lepers. At Memramcook (West Co.) he built a stone church, convent, and college. On Saturday his remains will be interred as he himself had directed in a vault beneath the High Altar of the Church of Memramcook.

Vol 23 No. 1219 Oct. 3, 1865 Saint John, Saint John: Morning Telegraph.

Lazaretto at Tracadie (Glouc. Co.) – leprosy – Havier BRADIEU, age 56, was born in Tracadie. (see original)

Vol 75 No. 57 Sept 18, 1889 Westmoreland Moncton: The Times.

Among The Lepers: The Origin and Spread of Leprosy Among the New Brunswick Fishing Folk: The Lazaretto at Tracadie . . . One sultry August afternoon in the year 1828, Rev. deBellefeuille was called upon to bury a woman named Ursule LANDRY who had died of a mysterious and loathsome disease. (See original)

Note by Mary Lynn Smith: Ursule Benoit (nee Landry) was labeled the first case by the 1844 medical commission convened after the arrival of parish priest Francois Xavier Lafrance in the Tracadie area. People with tell-tale signs of leprosy resided in the community, and Lafrance quickly raised the alarm along with local resident John Young, who in 1841 expressed public concern about the existence of a frightening community malady. Older settlers advised the commissioners that Ursule, born circa 1774 in the Caraquet area, had exhibited signs of leprosy as early as 1817. She was a granddaughter of Alexis Landry, a prominent Acadian refugee who had returned from exile to the Caraquet area. When the previously undiagnosed ‘maladie’ became ‘LEPROSY’ the afflicted were swiftly isolated on Sheldrake Island, a former cholera quarantine station at the mouth of the Miramichi River. Conditions for the banished on that desolate Island were indescribably horrific. In 1849 the surviving inmates were removed to a new Lazaretto at Tracadie.

Vol 87 No. 2455, March 15, 1893 Northumberland Chatham: The World

Chas. H. LABILLOIS has been in the House since 1882 when he helped turn out the Hanington government . . . His paternal ancestors were natives of Britany. His grandfather, a surgeon under Napoleon, came to America in 1816, and was in charge of the Tracadie Lazaratto for a time. On his mother’s side, he is of Irish descent. He was born at Dalhousie (Rest. Co.) and educated at the Dalhousie Grammar School.

From Children of Lazarus The Story of the Lazaretto at Tracadie by M.J. Losier (Author) Research: Celine Pinet, Published by Fiddlehead Poetry Books, and Goose Lane Editions, Fredericton, New Brunswick, 1984.

Excerpt from Page 9

It was James Young, a Scottish immigrant, settled in Tracadie since 1825, who brought the disease to the attention of Sheriff Henry Baldwin of the County of Gloucester around 1841. At this time, the Sheriff recommended the community try to contain the disease by a voluntary contribution of funds to alleviate the poverty in which he said flourished.

Excerpt from Page 8

Dr. Key, Skene, Toldervy, and Gordon and the Rev. Mr. Lafrance left Chatham on the morning of Thursday last for the purpose of investigating the nature, origin and extent of the frightful . . . disease now existing in Neguac, Tracadie, and Tabusintac . . . as a result of their investigation . . . they reported that it is their opinion that it has no affinity to scrofula, and that the idea prevalent, that it is owing to the poor diet of the French settlers, and their filthy habits is not correct for they found it in some of the cleanest dwellings and most respectable families. (The New Brunswick Courier, Saint John, New Brunswick, April 13, 1844)

Note by Mary Lynn Smith: Children of Lazarus The Story of the Lazaretto at Tracadie is a highly-recommended resource. Sincere thanks to Mary Jane Losier and Celine Pinet for their excellent work.

From PANB – Dictionary of Miramichi Biography.

KEY, Alexander (1795-1851)

Doctor, bap. Dundee Scot. 6 Dec. 1795

died Chatham 26 May 1851 – m. 1823 Margaret Henderson

d/o Patrick and Elizabeth Henderson

After 5 years in Edinburgh, Scotland where he got a medical degree – came to Chatham in 1816 – est. a practice . . .

Key was the senior health officer for port of Miramichi for most of his career . . . major responsibility for ship inspections and imposition of quarantine . . . still active in 1847 when passengers and crew of the Looshtauk were confined to Middle Island

. . . Later he attended typhus patients on the Island, including both Dr. John Vondy and Captain John M. Thain of the Looshtauk . . .

Key was the first doctor to undertake a methodical study of the outbreak of the outbreak of leprosy in northeastern New Brunswick . . . while he was aware of the existence of the illness from the 1820’s onward, it was not until 1844 that provincial authorities set about to determine “the nature, origin, and extent of the frightful and loathsome disease at Neguac, Tracadie, and Tabusintac.” That year a medical commission, of which he was the only Miramichi member, concluded an investigation and confirmed that the disease was leprosy . . . more than 20 cases, all traceable, it was thought to a single source. A special Northumberland and Gloucester Board of Health was created to manage the problem. Key was both a member of the board and medical officer in charge of the lazaretto which was opened on Sheldrake Island for the incarceration of victims. Much can be gleaned about his work and thought on subject . . . from a report of his printed in The Gleaner Spring 1945. Unlike some of his contemporaries, who contended that it was of genetic origin, he held that it was contagious, though he considered it possible that some were predisposed to get it.

Typhus

Typhus (spotted fever) is caused by the organism Rickettsia prowazekii or Orientiabacteria. Infested mites, fleas, or lice can pass the typhus microbe to people. Sailors, traders, soldiers, and the poor were the great propagators of typhus. Confined spaces and dirty clothing provided ideal conditions for transmission of the disease.

All it would take was a scratch, and the typhus germ would transfer from lice excrement into the body. “General Typhus” could be overpowering. For example, Napoleon lost 80,000 soldiers to typhus in one month, after beginning his disastrous attack on Russia in June 1812.

From PANB Daniel F. Johnson’s Newspapers

Vol 11, No 3110, July 6 1847 Northumberland Chatham: The Gleaner and Northumberland Schediasma

d. Tuesday morn., Middle Island (North Co.) John VONDY, Esq., Health Officer at Lazaretto, age 27.

Vol. 11, No. 2373, July 10 1847 Saint John, Saint John: New Brunswick Courier

It is our painful duty to record the death of Dr. VONDY, Health Officer at the Lazaretto. He fell sacrifice to the alarming disease with which the passengers of the ill fated ship “Looshtauk” were visited and expired Friday morn. His remains were placed in a double coffin and conveyed from Middle Island to Coulson’s slip and from thence to St. Paul’s Churchyard. (North. Co.). Miss VONDY, his sister, attended him during his death illness.

Vol. 11, No. 2372, July 10, 1847 Saint John, Saint John: New Brunswick Courier

Miramichi Quarantine – George McAULEY mate of “Looshtauk” is among the number who died at the Lazaretto. His mother lives at Spring Hill near Fredericton. (York Co.). He was married immediately before leaving Liverpool and lodged in Park Lane.

Notes from Mary Lynn Smith: The Looshtauk was a ‘coffin ship’ carrying Irish from the land of the Great Famine. In 1847 she departed Liverpool, England for Quebec City. Sickness on board forced a diversion by Captain Thain to Miramichi, from whence the ship was towed to nearby Middle Island for quarantine (about two kilometers east of Chatham). Doctor John Vondy, who had recently set up practice in Chatham, went to Middle Island and contracted typhus soon after. He did not survive, though Captain Thain, also afflicted, was luckier. 146 of the 462 on board perished during the crossing. Of the 316 isolated on Middle Island: 96 died, 197 were discharged at Chatham, and 53 went on to Quebec City (a 53% loss rate).

Mosquitoes

From New Brunswick – The Story of our Province by George MacBeath, Ph.D. and Dorothy Chamberlin, M.A., W.J. Gage Ltd., Toronto, 1965.

Page 132

Would all the newcomers be happy? Here is a letter from a Chignecto settler who felt otherwise:

To: William Harrison

Rillington, Yorkshire, England

June 30th, 1774Dear Cousin,

Hoping these lines will find you in good health, as we are all at present bless God for it. We have all gotten safe to Nova Scotia, but do not like it at all, and a great many besides us, and are coming back to England again, all that can get back. We do not like the country, nor never shall. The mosquitos are a terrible plague in this country. You may think that mosquitos cannot hurt, but if you do you are mistaken, for they will swell your legs and hands so that some persons are both blind and lame for some days. They grow worse every year and they bite the English the worst.From your well wisher,

Luke Harrison