wishart period

Chapter 3

We return to The Charlotte Taylor Story. It is 1785 and the Widow Blake is still residing in the Black Brook area of the Miramichi River with four young children. The oldest, Elizabeth Williams (Williamson) is about ten years of age. John, Jane (perhaps Mary Jane) and Robert Blake, children of the deceased Captain John Blake, are all under the age of eight. There is a servant living with them on the south side of the river. According to the Daniel Micheau Survey (see Imagery/Maps Map 3. Daniel Micheau – Miramichi – 1785 Survey), the Widow Blake held Lots 8 and 9. John Murdoch and his family were down river from the Blakes on Lots 1 and 2. Daniel Menton’s name was on Lot 17, some distance up the river. It was noted by Daniel Micheau that Menton had been a Private in the disbanded Prince of Wales American Regiment, and that he had logs laid up to build a house. This is a very interesting annotation. Most members of the disbanded Prince of Wales American Regiment received their Land Grants on the Keswick River, near Fredericton, New Brunswick. It appears that only two men bypassed that place and came directly to the Miramichi area. One was Daniel Menton and the other was a sergeant named Philip Hierlihy. Philip was destined to marry Charlotte Blake (nee Taylor) in September of 1787. There are no names recorded on Lots 3 to 7 below the Blakes, nor any on Lots 10 to 16 above them. There are no acreages marked on the Survey. It does show the location of houses or buildings on these Lots all along the Miramichi River to the lines of the Davidson and Cort Grant. The Murdoch house was situated on Lot 1 and the Blake house was on Lot 8. Daniel Micheau noted that ‘Old Setlers’ John Murdoch and Widow Blake had made considerable improvements.

The north side of the river appeared more heavily populated. Looking at this Survey we get a picture of the degree of settlement at that exact time. It must be noted however, that many settlers, especially the ‘old settlers’; were not happy or satisfied with this Survey. Many had received their original over-sized grants from the government in Nova Scotia, through Captain Boyle in 1777. The area was filling up with ‘new settlers’ – Loyalists, soldiers of disbanded regiments, and immigrants from the British Isles in the aftermath of the American Revolution. Surveys were being done and Land Grants were being reorganized under the auspices of the newly created Province of New Brunswick. This transitional period was a time of high anxiety for ‘old settlers’ as they fought to retain their original Nova Scotia Land Grants.

Looking at the Daniel Micheau Survey of 1785 it appeared that Widow Blake and her family were living a good distance from any neighbours at that time. She was five Lots from the Murdochs and seven from where Daniel Menton was preparing to build his house. But the Blakes may have had a ‘neighbour’ just above them in 1782 in the vicinity of Lot 10. Whether he was still beside them at the time this Survey was done is unknown. The information about this ‘neighbour’ was revealed in a letter, written to the Hon. Martin Hunter, President of his Majesty’s Council and Commander in Chief of the Province of New Brunswick. The Memorial of February 19, 1812 was written by John Blake, the eldest son of Captain John and Charlotte Blake. He was a young boy when his father died . He advised Hunter that his father John Blake Senior, “on account of his having been the first settler on the River of Miramichi, was allowed to hold lands on said River, and in particular in 1782 a quantity of land to the extent of 550 acres, on the southside thereof, and on the lower side of the lot belonging to William Wishart”. He went on to say that after the death of his father his mother had married a second time. Wishing to procure a title to the lands so that she could assign her right to her second husband, his mother applied for a grant of them. Her son stated that this was refused to her for many years on the grounds that it would have defrauded the legal heir of John Blake Senior. This view was apparently corroborated by Captain Lemmon who had been in the Miramichi area. After Captain Lemmon “was removed from St. John, the Mother of your Memorialist had again applied, and procured a Grant of the said Land excepting about 200 acres, now in the possession of your Memorialist, by which means the children of the said John Blake Senior have been deprived of what was their right”.

This Memorial, at first glance, seems to suggest that at some time in the year 1782 a man named William Wishart was living right beside the Blakes. However the Memorialist, John Blake Junior, may have been referring to his half-brother William Wishart. On April 6, 1812 their mother, Charlotte Hierlehy, deeded Lot 10 at Black Brook to her son William Wishart, two months after this Memorial was written. This Lot, granted to her on May 4, 1798, was part of the original 1777 Nova Scotia Grant of her late husband, John Blake Senior. Her son, John Blake Junior, probably knew of her intentions when he wrote to Hon. Martin Hunter. Perhaps this prompted him to pen his Memorial in the first place. In it he requested a Grant of vacant land to compensate him for the perceived ‘injustice’ he had suffered. The ambiguity in the Petition is unfortunate. Was the William Wishart mentioned in the Memorial a Blake ‘neighbour’ in the year 1782, or the half-brother of the Memorialist, John Blake Junior, when he wrote it in 1812?

Stories have been told of Charlotte snowshoeing to Fredericton, New Brunswick to settle her first husband’s estate. She needed the Governor’s assurance that she would retain Captain John Blake’s 1777 Nova Scotia Grant. There were two distinct problems. She had remarried, and in 1784 the Province of New Brunswick had been created. It would take years for the situation to be resolved. On May 4, 1798, Lot 8 – 161 acres, was granted to John Blake Junior. Lot 9 – 160 acres, was granted to Philip Hierlihy, a result of his service in the Prince of Wales American Regiment during the American Revolution. Lot 10 – 154 acres, was granted to Charlotte Hierlihy herself. The total acreage granted was 475 acres. This was somewhat less than the 550 acres that John Blake Senior is said, by his son, to have been originally granted (by the Nova Scotia government). Other accounts state that that the original Grant had been smaller, from 300 acres (Esther Clarke Wright) to 350 acres (Nova Scotial License). Complaints registered by ‘old settlers’ in their petitions of 1775 concerned the Daniel Micheau Survey of that same year. He had reduced their Lots to “40 roods only in front”, depriving them of a portion of their original granted lands. This may explain why the granted Lots 8, 9, and 10 in 1798 were in total 75 acres less than the original 550 acres supposedly granted by Nova Scotia in 1777.

The Memorial of John Blake Junior in 1812 clearly stated that his mother Charlotte Blake had married her second husband after the death of his father. John Blake Senior died sometime before March, 1785. Robert Blake, son of John and Charlotte Blake, was born in 1781 or 1782. The actual date of John Blake Senior’s death is unknown. There is no evidence that Charlotte Blake ever legally used the name Charlotte Wishart. On September 11, 1787, Charlotte Blake, not Charlotte Wishart, married Philip Hierlihy. But it has been frequently stated that William Wishart was the second husband of Charlotte Taylor. A baby named William Wishart was born to Charlotte in 1785 or 1786. It is possible that Charlotte married William Wishart soon after she became the Widow Blake. At that time widows were the most desirable of women, especially if they had property to contribute to the union. Remarriages frequently happened within a few days or even hours of widowhood.

This was a time of great upheaval on the Miramichi, in the aftermath of the American Revolution. The creation of New Brunswick in 1784, by division of the province of Nova Scotia, produced legal complications regarding the Grants of land originally registered in Nova Scotia. It took time to get the government bureaucracy of the infant Province up and running. There were frequent changes of ministries within the period 1782-1784 and within the administrative structures of governments in the colonies. Delays were caused by transportation and communication difficulties between London and the various governors of Halifax, Parrtown (Saint John), and Quebec. It probably affected all legal records during the transition, including the registration of marriages. The interval of Charlotte’s ‘widowhood’ between the death of Captain John Blake before March 1785, and the marriage of Charlotte and Philip Hierlihy on September 11, 1787 was inconsistent with the times. It was, generally speaking, too long for a relatively young woman who had property to be alone. Also, widows were looking for the added security that a swift remarriage would provide for themselves and their children.

Charlotte’s son William Wishart died at the age of 65, on April 26, 1851, according to his obituary in the April 28, 1851 edition of The Gleaner. If this age of 65 years was accurate, then he was born between April 27, 1785 and April 26, 1786. He was buried at Riverside Cemetery in Tabusintac and his tombstone gives his date of death as April 28, 1851 at the age of 64. If he was 64 when he died on April 26, 1851, then he was born between April 27, 1786 and April 26, 1787. By early 1787 Charlotte had 5 children; her eldest, Elizabeth, had probably passed her 11th birthday. She was no doubt a mature young girl by then, and very helpful with the four younger children. A large part of each child’s day, once they reached a certain age, involved domestic duties. Perhaps Charlotte schooled the little ones herself until such time as a teacher came to the area. The older boys were already learning the ropes of the trades that would enable them to make their livings on their own.

We will leave the family alone for awhile at this point in the Story and travel a distance up the Miramichi River to Lot 3 north side. On his 1785 Survey, Daniel Micheau noted that Lot 3 was “improved and now possessed” by Alexander Wishart. William Wishart, brother of Alexander, is believed to have been Charlotte’s second husband/partner and the father of her son, William Wishart. The life of the mysterious Mr. Wishart, Charlotte’s most enigmatic partner, can perhaps be explained by looking into the activities of the Messrs. Wishart. The name Wishart is a surname of Scotland; its meaning ‘prudent, sagacious’. The most famous throughout history was the George Wischart who was one of the primary movers of the early Presbyterian Church in Scotland. Another George Wischart was burned for heresy in 1545 or 1546 at St. Andrews. The Scottish roots of the Wishart line run back to ancient times in Forfarshire when the name was Guishard. The Messrs. Wishart came to the Miramichi, as did William Davidson, to establish a fishing and trading business there. They hoped to succeed by utilizing their expertise in the Scottish method of curing salmon. The American Revolution would, however, frustrate and interrupt any realization of their plans.

As we paddle up the Miramichi on September 1, 1785 to the house of Alexander Wishart, we cross the wide expanse from Charlotte’s home at Black Brook to the north side of the River. We sight first the house of Alexander Taylor on Lot 63. Destined to become a Justice of the peace for Northumberland County, he had arrived from Scotland with his wife and six children in 1784. His sister Agnes Brown settled in the area some years before him, and she is probably the reason behind his emigration to the area. It was thought by many that Charlotte Taylor was also his sister, I suppose because they had the same last name. A search of his background in Speymouth, Scotland revealed that she was not. His ancestors were “of sanguinity to His Grace, the Duke of Gordon” in Scotland. He boasted that one of his sisters had wet-nursed children of the Duke and other aristocratic personages. His father Patrick Taylor, or Peter as he was commonly referred to, had a bit of a reputation. He had fathered an illegitimate daughter named Marjorie Wishart, before his wedding to Helen Gordon.

Alexander Taylor was baptized on January 14, 1749 by a priest named John Godsman. This priest is believed to have founded St. Ninians Chapel at Tynet near Dallachy, Scotland. It was originally disguised as a cowshed, and is the oldest surviving Roman Catholic place of worship in Scotland. It is interesting to note here that William Davidson had returned to the Miramichi after his exile in Maugerville, New Brunswick during the years of the American Revolution. He had assumed the name of his maternal grandfather, William Davidson, when he first emigrated to North America from Scotland. He had in fact been born John Godsman and why he changed his name is a mystery, although it may have had something to do with religion. Alexander Taylor was responsible for some of the Scottish emigration that took place around that time, as he assisted the settlement of family and acquaintances from his home in Scotland to the Miramichi area. It was certainly true that “where one Scot went, others soon followed”.

I consult my copy of the 1785 Daniel Micheau Survey and discover that Martin Lyons, ‘Old Setler’, has laid up logs for a house and made other small improvements on Lot 46. Andrew Cheap is marked for Lot 40. On the south side lies Middle Island. Captain Shank is marked for Lot 37, and Thomas Yeomans, ‘Old Setler’ is already settled on Lot 32. On Lot 28 Daniel Monro, ‘old inhabitant’, has laid up logs for a house. John Delesdernier, ‘Old Setler’, has improved and taken possession of Lot 17 and Mark Delsdernier, on Lot 10, has put up a small house. We are approaching Lot 3 now. Across the River we can see Canadian Point, the valuable marshland that is desired by all. We pass Lot 4, where William Ledden, a “refugee from Quebec”, has “put up and newly furnished a house”. Finally we see Alexander Wishart’s house on Lot 3.

Neighbour Henry McColm’s Lot 2 borders on the lines of the 100,000 acre Davidson and Cort Grant of 1765. This Grant was escheated (revoked) a month ago on August 3, 1785 for reasons of non-compliance with its original terms of settlement. This won’t be the end of William Davidson, however, as he will later receive a new reduced Grant of 14,450 acres on June 7, 1786. It will consist of separate parcels of land on both the south west and north west branches of the Miramichi, and he will not be required to bring in any settlers this time. William Davidson was not warmly received upon his return from Maugerville after the end of the American Revolution. Those who had stayed or arrived on the Miramichi during those difficult years held feelings of bitterness and hostility towards him. William Davidson would, however, continue to be a most influential man in the development of the area for years to come. He would be named a Justice of the Peace, and a Judge of the Court of Common Pleas for the County of Northumberland. Naturally there would be jealousy of his success. We are now at the end of our long day’s journey, near Strawberry Point and Beaubear’s Island, beyond which the Miramichi forks into the North West and the South West Branches.

It is a fine September day, as we arrive at the house of Alexander Wishart on Lot 3 north side. Our journey down the Miramich River has been an enlightening experience. It will now be easier to understand some events of the preceding eight months. In a January 10, 1785 Memorial, Robert Reid and Andrew Cheap provided interesting background information on the Messrs. Wishart. They had entered into a co-partnery, Messrs. Wishart and Co., with the two Wishart brothers. Their patron was Captain Shank. Wishart and Co. planned to establish a salmon fishery on the lot that had been the property of the Messrs. Wishart until 1779. In that year, during the American revolution, they were forced to abandon it. They had been plundered of their effects, first by the crews of different Privateers of the “Rebel States”, and second by “savages”. Consequently they were forced to flee for refuge to Quebec where General Haldimand appointed them Lieutenants in His Majesty’s Service on the Lakes. In their absence, William Leadan took possession of houses belonging to the Messrs. Wishart. In January of 1785, he was still there, despite repeated attempts to remove him.

On that same date Robert Reid carried with him the Memorial of Alexander Wishart, and it too is full of interesting biographical information. In it he related that he and his brother had settled on the Miramichi River in 1775. There they built a house, a shed for curing salmon, and cleared land on Lot 3. They also occupied Lots 2 through 9. In 1778 they were plundered of a very considerable amount by the “privateers of the States.” In 1779, plundered again by “savages”, they lost everything. They went to Quebec aboard HMS Viper under the command of Captain John Augustus Hervey (see Imagery/Selected Topical Images, Abbreviated Hervey Family Tree). There they both obtained commissions to serve His Majesty on Lake Champlain. Their commander was Captain William Chambers. At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, six men, entitled to lands, entered into a fishing, merchandising, and farming co-partnery. They located to the Miramichi River lands formerly occupied by Alexander Wishart and his brother. They were interrupted by William Ledden during their arrival last year (1784) with a cargo from London. Ledden had taken violent possession of the Wishart house and advised them that he had received a Grant of it from William Davidson. It appears for a time that the Wisharts actually shared the house with William Ledden, out of necessity. They felt that their valuable property was exposed to many “risques” in this arrangement. William Ledden persisted in keeping possession of his house, although he well knew that it was Wishart property. Alexander Wishart went on to say that “he (William Ledden) is lickways marked to Lot 4 which cuts off the whole fishing on Lot 3. He is a man of very indifferent character, and never was of any service to King, or Country, but I have had the honour to serve His Majesty in the two late wars, so that I hope your Excellency will be pleased to honour me with your advice relative to the memorial”.

A letter was attached to the Memorial of Alexander Wishart. It was written a few months earlier by John Shank on August 26, 1784, and addressed to Messrs. Wishart, Hutchison and Co. Shank notified the Wisharts that he had discussed their land problems with Governor Wentworth, General of all the King’s Woods in America. Governor Wentworth advised Wishart and Co., through John Shank, that he would order a survey of the land and put them in possession of it. He requested they forward him a letter outlining when they would like to take possession. This letter/attachment followed the 29 September 1783 (Quebec) Memorial to Frederick Haldimand requesting that Alexander and William Wishart be “put on the same footing as other Loyalists in respect of land.”

It is not known whether the 1784 arrival of the Wisharts with ‘cargo’ was their first trip back to the Miramichi after the American Revolution. That War officially ended in 1783 and some of the participants had probably received their discharges before the Peace. The date that William Ledden moved onto the Wishart property is also unknown although he was supposedly in the Miramichi area in 1780. He had been a cooper in His Majesty’s Navy but it is stated that he left the navy early. These dates are important in determining whether the ‘neighbour’ William Wishart could have resided beside the Blakes in 1782.

During the American Revolutionary War, the Miramichi River was terrorized by American privateers. William Davidson and the Wishart brothers, located up river, were particularly hard hit. The vessels were manned by ruthless crews, supposedly licensed to capture enemy ships. They went much farther than this mandate, however, and for years they raided and destroyed property along the north Atlantic coast. They were nothing more than ruthless, lawless pirates. Davidson profited handsomely from an interim masting timber business that he established in Maugerville, N.B., while the Wisharts served out the War in service to their country.

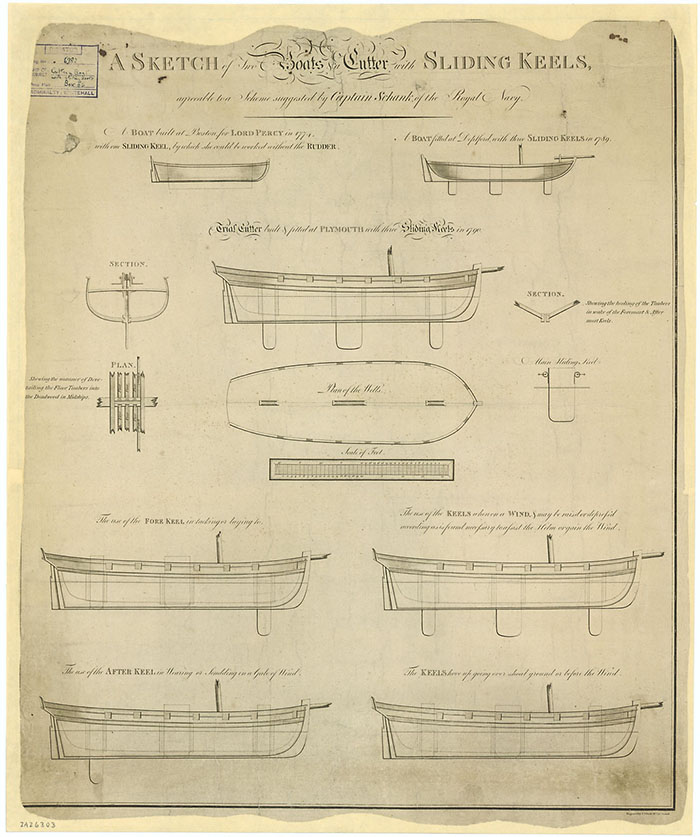

In 1779 they were both commissioned as Second Lieutenants by Governor Haldimand (in Quebec), Alexander on the 20th of November and William the following day. Haldimand had been a Swiss soldier of war before he entered British service during the SevenYears’ War, and was a 61-year-old bachelor in 1779. During previous stays he had purchased lands at Shepody (New Brunswick), and a seigneury in Gaspe (Quebec). Haldimand tried to secure the defenses of Canada on the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. At Carleton Island and Niagara, on Lake Ontario, he had ships built to command the waters and to transport soldiers and supplies. These ships were manned by the Provincial Marine, under British naval officers. The Wishart brothers probably served on one of them, perhaps under Captain Shank, who would become the patron of Wishart and Co. Captain Shank had entered the navy in 1758. He served with General Burgoyne in 1776 and he built the first vessel for use on Lake Champlain. Shank was considered a mechanical genius, the first to invent and build a vessel with a sliding keel. Sudden storms and rough waters made navigation of the inland lakes hazardous and stressful. The rapids between Montreal and Lake Ontario required all stores to be dragged upstream in bateaux, or frequently carried by Canadian voyageurs. General Haldimand, blowing out rocks and digging small canals between Montreal and Lake St. Francis, had unknowingly started the work of the future St. Lawrence Waterway.

The Wisharts probably assumed that their loyalty and service to Great Britain would be in some way respected and perhaps rewarded post War. When they came back to the Miramichi in 1784 or earlier, after a long absence, they discovered that everything had changed. Many ‘new settlers’ had settled on the lands of those who had been forced to flee the area. Although his Miramichi establishment had been completely destroyed, William Davidson was able to rebuild. He also had title to his lands, although the acreage would be significantly reduced by 1786. There were benefits that outweighed his losses however. He no longer had the onerous task of settling others on his property. He was, over time, able to regain his position of wealth and prominence in the area. The Wisharts would not be as fortunate.

During 1785, squabbling over Land Grants intensified. In March of that year thirty families of Loyalists had obtained 15,000 acres on the Miramich River. This inspired a group of apprehensive ‘old settlers’ to petition for the ‘Kinadian Point’ marsh that they had used since 1777. Among the signees were John Toshen, William Atkinson, and Alexander Henderson. On March 5th, Alexander Henderson, who by then had six sons and two daughters, petitioned for lands adjacent to his property. He had been located on the Miramichi since 1776, in the Morefields area, and wanted lands for his adult sons and other emigrants that he had brought out from Scotland. On March 8th, William Brown, an ‘old settler’, petitioned for a Grant of his original Nova Scotia lot of 1777. He also requested a lot for his son Robert, who had served in Colbeck’s Battalion on the Island of St. John (Prince Edward Island), during the American Revolution. His Petition was conveyed to Fredericton by John Mark Crank Delesdernier, who acted as Agent for many of the ‘old settlers’. In April of 1785 the government of New Brunswick decided to grant no more than 200 acres to each settler, whether he had a family or not. In April Martin Lyons, ‘old settler’, referred to his previous Memorial of July 19, 1782. In it he and Alexander Henderson, another ‘old settler’, had requested Grants of their original 1777 Nova Scotia Land Licenses. Over three years later they still did not have an answer.

William Cort, son of the late John Cort, sent a letter to Governor Carleton on May 18, 1785. John Cort had been the partner of William Davidson in 1765. His son wrote about the “many and repeated wrongs and injuries received from different inhabitants of this Place”. He requested that “all His majesty’s loyal subjects may be secured in their lives and properties from the unlawful attempts of People accustomed to Robbery and Plunder”. William Cort had returned to the Miramichi to finalize his deceased father’s affairs. People had taken possession of his father’s Books, papers, and furniture, under false pretenses and he arrived just in time to prevent them from demolishing the house and “Fishing Furniture”. When he requested that they return to him what they had stolen, he was treated to a barrage of abuse and bad language.

The summer of 1785 brought many changes to the Miramichi River area. On July 9th, Benjamin Marston, the first Sheriff of Northumberland County, arrived at Wilson’s Point on the Miramichi River. He administered the oath of office to John Wilson, Esq., Justice of the Peace. A snobbish Loyalist and Harvard graduate, Marston had been a well off merchant in Marblehead, Massachusetts before the American Revolution. His mother was a sister of Edward Winslow. Forced to evacuate to Halifax with the British forces in 1776, he was pronounced a traitor and banished from the State of Massachusetts in 1778. During his short stay in the Miramichi he kept an interesting diary, very descriptive of life on the Miramichi. The area was not what he had hoped it would be, its inhabitants living in a sparse manner along the banks of the River. The fishery was worthy of his attention, but it was failing. He attributed this to people like William Davidson “extending nets fairly across River to utter exclusion of Savages above”. Sunday, July 24th, Sheriff Marston put up a notice that he would soon publish the Charter of the County. This brought a considerable number of local inhabitants together, most of whom, he observed, “were drunk at his expense”. He considered the people to be illiterate, much given to drunkenness, and completely dependent on the salmon fishery. In his opinion Law and Order and the Gospel were needed to civilize their manners. For the rest of July he engaged in laying out lands on the Little South West Miramichi.

In August Benjamin Stymiest, a native of Gravesend on Long Island in New York, petitioned for land. He had been settled at Hampstead at the beginning of the Late Rebellion. He fled to Staten Island and when New York was evacuated he came to New Brunswick. He had been twelve months in Northumberland County and he was beginning to “make a settlement at Bettvin” (Bay du Vin) on Miramichi Bay. At the time of his Petition he had a wife and five unmarried children all above the age of ten. His son Benjamin Stymiest Jr. would one day marry Charlotte Mary Hierlihy, a daughter of Charlotte and Philip Hierlihy. A group of settlers, on August 15, 1785, recommended John Tushie for Pilot. They stated that he had acted as Pilot on the River since 1775 and had never lost a vessel. Francis Harriman of the HMS Viper certified that he had been piloted “up and donne” this River several times by John Tushie. The recommendation was signed by Alex. Wishart, Shipmaster; Robert Reid; John Watson and Alex. Henderson. It has been written that Captain John Blake was for a time a Pilot on the Miramichi River. Could this be a recommendation for John Tushie to take over the duties of the recently deceased Captain Blake?

It is the morning of September 2, 1785 and we have enjoyed our overnight visit at the home of Alexander Wishart. His difficulties with his neighbour William Ledden on Lot 4 are still unresolved. Now it is time to travel back down the Miramichi River to Black Brook and catch up with Charlotte and her family again. We cross the River to the south side just below the marshlands at Canadian Point. The first house we see is on Lot 52, where considerable improvements have been made by ‘Old Setlers’ John Tushea and John Fitzgerald. They have also asked for Lot 51. Just two months ago the elderly John Fitzgerald “went out to set a Nett and was drowned”. In the aftermath of this unfortunate accident a request was penned to Edward Winslow by Captain R.F. Brownrigg on June 29, 1785. He was a new arrival to the area and had “opened a store for the present at Mr. Mark Delesdernier’s” until such time as he was fortunate enough to get his own Land Grant on the River. He felt that there was an urgent need for an area coroner, “as several people have been drowned and no one to enquire how”. He offered himself for the position, although he wondered if his title as a Justice of the Peace in the County of Halifax would be “derogating from that appointment”. Some distance down River we pass by the house of ‘Old Setler’ John Parsons on Lot 44. Lot 42 is marked for Murdoch McDonald and Lot 41 for Alex. McDonald. They are both “late of the Queen’s Rangers”. William Brown on Lot 33 and Robert England on Lot 31 are both “lately of Europe”. Our journey takes us next past Middle Island. Behind it Lot 26 is marked for Gregor McKinnon, “Sergt. Carolina Volunteers”. We pass by Lot 17 where Daniel Menton is laying up logs. And a short time later we approach the Blake house. It’s been an interesting voyage and we’ve returned with a lot more knowledge about the Wisharts and about the other settlers down River on the ‘banks’ of the Miramichi. We will now continue on with Charlotte’s Story.

On Sunday September 4th Benjamin Marston, Sheriff of Northumberland County, left his lodging at Squire Wilson’s at Wilson’s Point. He relocated down the River to Mark Delesdernier’s house, at a cost of 10 shillings per week, because he and Delesdernier were starting some survey work together. For a time Marston served as Surveyor General of the King’s Woods. The next day John Malcolm presented a Memorial for a group of “ancient inhabitants”. They had for many years improved and enjoyed in common a tract of marsh or meadowland called Canadian Point. They mentioned how it had materially assisted them in their period of distress during the American Revolution. They had sent Mark Delesdernier to Parrtown (Saint John, New Brunswick) in March of 1785 with a Petition for this marsh land. It was never presented, “some collusion or artifice having prevented its natural course”. They advised that Mr. John Wilson, Esq. had been appointed a magistrate, but not by their approbation, as they were “strangers to his capacity”. He was the only person, according to them, who employed people to cut down hay on the marsh. Sheriff Benjamin Marston had forbidden him from cutting or carrying away the hay until the “government’s pleasure was known”. But the people he employed said “was he to order them they would have cut down your Memorialists’ corn” and that they had been “dispossessed of their ancient rights by strangers”. They felt they had a prior claim to the meadows through their long possession and cultivation and that their marsh hay was being destroyed and “violently cut down before half grown”. Their final complaint was directed at Daniel Micheau, the surveyor of the 1785 Survey. They were unhappy that he had laid out to them “40 roods only in front”. This meant that they had been deprived of a great part of their uncleared lands. They requested that Benjamin Marston be permitted to make a new survey. Among the “ancient inhabitants” who signed this Petition were: Martin Lyons, Alex. Henderson, John Henderson, Robert Beck, Thomas Yeomans, William Drisdail, William Atkinson, John Parsons, John Tushea, John Malcolm, and William Brown. On September 20, 1785 the marsh at Canadian Point was assigned to them in common. It is interesting that ‘old settler’ Charlotte Blake did not sign this Petition.

September 6th, Alexander Henderson submitted a Petition. The previous fall he had petitioned the government in Halifax for license to build saw and gristmills. This was declined “on account of Government being separate” and he was now applying to Governor Carleton in New Brunswick. Alexander Henderson advised that he had cleared and erected two habitable houses on the spot where the mills would be located. He and other old inhabitants complained of the injustice done by Mr. Michaud, “the survier, who had subtilly alloted all Houses and improvements belonging to your petitioner, marking the same down in plan of river in name of others etc’. He asked that Benjamin Marston be empowered to take a new survey of the River. Robert Reid, the owner of a store on the Miramichi River, was sworn in as the first coroner of Northumberland County on September 24th by Benjamin Marston. In time he would succeed both Marston and John Mark Delesdernier as Sheriff. On November 17, 1875 William Davidson and attourney Elias Hardy were elected to represent Northumberland County in the General Assembly. There were twenty elected members including themselves. The right to vote was given to any white male person, 21 and over, who had resided in the province three months. The right was not extended to French voters; they were required to take the oath of allegiance. Benjamin Marston felt that William Davidson had been elected due to his influence over certain people. Five days later Benjamin Marston left home on a canoe trip with John Mark Delesdernier during which they crossed the Little Napan and Napan Rivers. They visited the home of home of George Murdoch and family, who lived down River from the Blakes, and crossed the Miramichi River to spend the night at the home of James English. The weather was very enjoyable although winter was approaching.

On January 31, 1786 William Milne and a group of ‘new settlers’ presented a Memorial to Governor Carleton , City of St. John. They stated that the ‘old settlers’ had their proportion of marsh land, but were dissatisfied. Although they had the best part, they wanted to divide the remainder in common with the ‘new settlers’. The ‘new settlers’ wanted to divide the remaining marsh lands among themselves in proportion of their several lots. They were concerned that the ‘old settlers’ wanted a reduction or regulation of fishing to the great detriment of the ‘new settlers’ on the north end of the River. They pleaded that it not be granted without investigation. They also requested the appointment of a man to regulate the dispute for “there isn’t a man here but what is interested or lieable to be corrupted by the old settlers”. They emphasized that “as the medow of Canadian Point has been loted to the ‘old settlers’ there will be a stop put to cutting hay at Napping (Napan) Marsh as when they cut it they let it lay on the ground until it is burned”. The petitioners begged “the privilege of the meadow Napping (Napan), as the land adjoining it is not fit for cultivating”. The ‘new settlers’ names that endorsed this Petition were: John Murdoch, Charlotte Blake, John English, Jno. and Andrew Hay, James Roy, Donald McDonald, James English, James Innis, Thos. Davison, Thos. Hutton, Daniel Minton, George Murdoch, William and John Simpson, William Milne, Alex. Taylor etc. Louise Manny, respected local librarian, noted that the signatures on this Petition were all in the same writing except those of Milne and Taylor. If Charlotte Blake did share the sentiments of this Petition, then she had crossed the line – she stopped being an ‘old settler’ and became a ‘new settler’. George Murdoch appeared to have done the same. But these were not their signatures, and the Petition cannot be legally binding to them. The compatriot of Philip Hierlihy, Daniel Minton, late of the Prince of Wales American Regiment, also ‘signed’ this Petition. In 1787 Philip Hierlihy, ‘new settler’ would marry Charlotte Blake.

On January 22, 1786, Benjamin Marston returned home, fatigued after a march of 30 miles across “sharp, frozen crust”. He wrote Otho Robichaux that he would “take Savoys oxen and send him a Petition for the French people”. Sunday, February 18th, he was informed by an elderly man of good character that if “Stewart, whom I have located next to Martin Lyons, should fail of getting that lot then I will be in danger if I return to this River again”. This entry in the Diary of Benjamin Marston is revealing evidence of the cut-throat nature of Land Grant activities at that time on the Miramichi River. When Marston failed to get his own masting contract he traveled to Halifax to get mill irons for a sawmill he planned to build. From July to September labourers framed the mill, laid down sills, and cut boards. He continued throughout this time to engage in his profession as surveyor. On October 20, 1786 Benjamin Marston sailed to England in an attempt to claim compensation for the considerable losses he had suffered during the American Revolution. The small compensation he received rendered him financially insolvent. Instead of returning to the Miramichi River as he had planned, he journeyed on surveying business to Africa where he died of African fever on August 10, 1792.

On February 18, 1786 the indefatigable Alexander Wishart sent off another letter. In it he stated that he had not received a reply to his previous Memorial of January 10, 1785. He reiterated that he was “expecting the lands and fishing places formerly occupied by me and brother was to be continued or part at least of the fishing place on it, but is intirely cut off by Lott 4, which was occupied by us for several years and seems to have loast it, by our services to Government … Lott 3 is all a flat muddy sand a good distance from the shoar so that we cannot sett a nett anywhere on this Lott, but in the centre between the two Lotts, but in opposition to us, the netts from Lott 4 is set right in front of ours and so close that they often intangle with ours, to the Great Detterment of our Business. For further particulars refer to the Bearer, Mr. Adam McAllen, a partner of ours”. Alexander Wishart’s oft-mentioned ‘brother’ was probably still alive on that February day in 1786, which is why Alexander wrote “a partner of ours” and not ‘a partner of mine’ in his letter/Petition. In the document he formally introduced their “Bearer” and co-partner, Mr. McAllen who had served with them on Lake Champlain during the American Revolutionary War.

On September 15, 1786 a Petition was sent to Governor Carleton from Alexander Taylor and others. In it five settlers who had been duly located by Mr. Mesheaux (Daniel Michaud) asked for a ‘conjunct’ or ‘principal’ grant among the whole of them, specifying “each man’s lot to himself and his heirs with a copy of same to each”. They had the money to pay for one Principal Grant and their request was complied with. This was an important grant. The fees levied through the Land Grant process were onerous, as many individuals involved in the process received remuneration, and a great deal of money could be saved by these ‘conjunct’ Grants. One set of fees only were levied to Alexander Taylor and group, instead of five times that for five individual Grants. On December 30, 1787, Alexander Wishart sent another Petition to Governor Carleton. Tellingly, there was no mention of his brother who was presumably deceased at that time. He stated that the remains of a house that he had built on Lot 10 north side of Miramichi River in 1777, were still there. This house was designed to “Build a Miln, as there is a small rivulet falls into this place”. But being plundered of all his effects, “thought it more prudent to leave this place and serve his King and country as he had done the last French war, and having received no lands for his service … asks for this lot”. He was advised that it had already been granted to Mr. Delesdernier.

In January, 1787 Alex. Wishart, John Willson, Justice of the Peace and Robert Reid crafted a Petition together. They did so to inform government of the lots of land on the Miramichi River that “are located to persons that are not nor never was Residenters here and as they are gone to difrant parts it is thought never will be improved by them, as they have been absent a long time”. They affixed a list of names to their Petition. On May 12th, John Willson sent a Petition to Governor Carleton from the Township of Newcastle, County of Northumberland. He expressed concern about the “disorderly Riots” going on in the area occasioned by people going to fish “contrary to all customs been known in this place. Most of them improve no land, but locate for the purpose of fishing, running up and down fishing in such a manner that they do and will deprive the Honest and Industrious people of the privileges Your Excellency bestowed upon them. They are now gone betwixt us and the River mouth with Drift, Drag, Stop nets and … other machines of fishing which is thought will destroy the whole by turning the course of them”. This matter had come to a head and bloodshed was a possibility as other settlers prepared to take the law into their own hands to stop these injurious practices. Judge Willson attempted to appeal to the more moderate among them by “sending express immediately” to Governor Carleton. In exchange the moderates promised that they would refrain from action until they received the “same requisition as other Counties and to hinder all the cross nets and merchants from other points from fishing as they did last season”. John Willson added that he was the only magistrate in the County and required advice on how to resolve this matter. He listed the names of the dissolute fishers: John Barr, Rob Shaw, John Carpenter, Jonathan Lufbury, James Davidson, and hands of William Davidson, Esq. Louise Manny, librarian, noted that this petition was not in John Willson’s handwriting but that it was his signature.

The Wishart Time was a short and contentious period of transition, and a time of serious dissension between ‘old and ancient inhabitants’ and ‘new settlers’. The Miramichi River had become part of the Province of New Brunswick; there was a new order, and a natural resistance to change. The arrival of Loyalists, disbanded soldiers, and other immigrants changed the tapestry of life on the Miramichi River. The many valiant attempts of Alexander Wishart to regain what he and his brother had lost during the American Revolution had gone nowhere, and Wishart and Co. was no more. There is no further mention of the Wisharts in the Petition records. Their Lot 3, from Henry to Hanover Streets in the old town of Newcastle (Miramichi, New Brunswick), was sold to the County in 1778. The house of their problem neighbour, William Ledden, survived the Great Miramichi Fire of 1825, when most of Newcastle burned to the ground. It was still standing in the 1920’s and was believed from its appearance to have been erected before the 1800s. If this information is correct then it was built by the Messrs.Wishart before they left the Miramichi River for Lake Champlain in 1779. William Ledden, for a time, rented out one of its large rooms to Justices for their court proceedings. He liked to irritate them and interrupt their proceedings by playing his fiddle. There is another other interesting Wishart story to relate but whether there is any truth to it is debatable. Dr. Nicholson, who had his office on McCullam Street in Newcastle, described it in a letter dated April 29, 1891. He had heard a story about an “old man Wishart” who had died in Douglastown. On his death, date unknown, nothing of value was found although he had been rumoured to be very wealthy. The field beside his house was subsequently ploughed up by two men and a box of money was found. Dr. Nicholson stated that these two had been hard pressed to earn a living before this incident was said to have occurred. For the rest of their lives, from that day, they were said to have lived “if not in affluence at least in comfort”. One other Wishart anecdote was included in the papers of Louise Manny, a librarian in the Newcastle, N.B. area. Christopher Wishart, a Douglastown shoemaker, merchant and school trustee died in 1853, after falling through a trap door at Gilmour, Rankin and Co.’s Store. He had been born in Dumfries, Scotland in 1791. Louise Manny noted that Wisharts had been settled on the Miramichi River before 1775. She wondered if this man might have been a relative.

William Wishart, the ‘brother’ or ‘neighbour’ or both, must have been deceased before the September 1787 marriage of Charlotte to Philip Hierlihy. Nothing more is known of him except that some of the descendants of his son, William Wishart, still reside in the Tabusintac and Wishart Point areas. It is said that he was buried in the old graveyard at Moorfields. During the Great Fire of 1825 an early Presbyterian Church was destroyed there. The first settled Minister on the Miramichi River, Rev. John Urquhart, is buried there. His granddaughter Louiza Urquhart married James William Hierlihy, a son of Charlotte and Philip Hierlihy. Many of the Miramichi area’s oldest settlers lie buried in Moorfields beneath beautifully carved and etched old tombstones.

William Wishart left behind a child who would be cherished in his absence. In her Deeds, registered April 6, 1812 and September 3, 1830, Charlotte Hierlehy/Hierlihy, with “love, and good will and affection”, and “natural affection and esteem” left her Land Grants at Black Brook and Tabusintac, N.B., to him. The next Chapter in the continuing The Charlotte Taylor Story will be related in Hierlihy Years – Chapter 4 (CT’s Story). It will begin on September 11, 1787, her wedding day to Philip Hierlihy.