aboriginal peoples

Aboriginal Peoples

From The Canadian Indian – Quebec and the Atlantic Provinces |

Excerpt from Pages 8 to 12

The Micmac

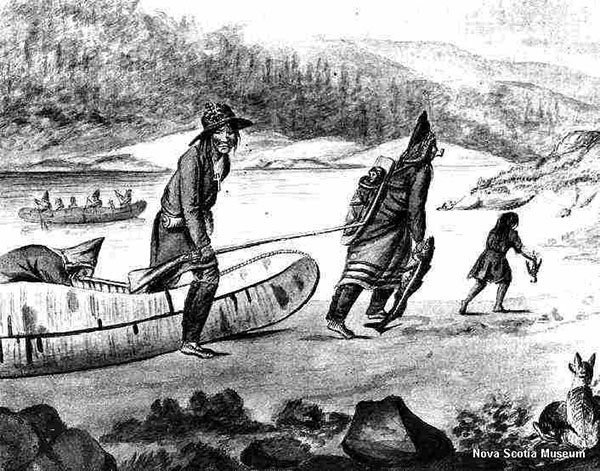

“… It is generally considered that the Micmac are the original native people of Nova Scotia, although today members of the tribe also live in New Brunswick and Quebec. The Indians of P.E.I. and the few in Newfoundland are also Micmac … Father Baird in his ‘Relation’ described much of the habits and characteristics of the people. ‘You could not’ he wrote, ‘distinguish the young men from the girls, except in the way of wearing their belts. For the women are girdled both above and below the stomach and are less rude than the men … Their clothes are trimmed with leather lace, which the women curry on the side that is not hairy. The often curry both sides of elk skin, then variegate it very prettily with paint put on in a lace pattern, and make gowns of it; from the same leather they make shoes and strings. The men do not wear trousers … they wear only a cloth to cover their nakedness’. Their dwellings were usually the conical bark wigwams, though some times when on the move, they used skins or matting made from reeds or pounded roots … The Micmac were excellent canoemen and much of their food came from the sea or the shore. They tapped the maples in the spring to make syrup, and used the berries of the woods and wild plants to supplement their diet, which was as varied and rich as that of the West Coast Indians. They early became allies of the French and it was many years after the English possession of Acadie that relations became amicable. Micmac warriors fought in the long border wars with the New Englanders, they being closely related to the native peoples of Maine and New Brunswick in language and culture. The Micmac people had a heritage of folktales and mythology which was carefully collected by early travelers and written down by scholars before it disappeared. These gave a rich legacy of Algonkin beliefs to the world.”

The Malecite

“… The Malecite people belong to the Abenaki group of the Algonkin peoples. Their ancestral home was always in New Brunswick, especially along the St. John River, where many of them still live. In European accounts, the earliest recorded notice of them was made by Samuel de Champlain in 1604. He spoke of their general friendliness and hospitality to himself and his party. ‘When we were all seated, they began to smoke, as was their custom before making any discourse. They made us presents of game and venison. All that day and night following they continued to sing and dance and feast until day reappeared. They were clothed in beaver skins’. When Fort la Tour was built on the St. John River, it became the trading centre for the Malecite. They greatly desired European goods, especially cooking pots and firearms. Their attachment to the French cause continued until 1763, by which time nearly all the Malecite had become Christian, and many had intermarried with French traders.”

The Algonkin Proper

“… All of the Indian people inhabiting Quebec and the Atlantic Provinces, with the exception of the Huron and the Mohawk, belong to the Algic or Algonkin family. There is no evidence in their known history that the Algonkin ever had a political union, or that, until they became involved in European wars, they ever fought together against a common enemy.”

Excerpt from Page 22

“… In 1753 the French government sent out a force of 2,300 men to build a chain of forts in the Ohio Valley from Canada to Louisiana and a wilderness war began. Fearing that the French might retake Nova Scotia from their fortress at Louisbourg, the Massachusetts governor, William Shirley, ordered John Winslow with a force of 2,000 volunteers to Acadia. The country was still inhabited by about 6,000 Acadian farmers who had lived under English rule, completely undisturbed for forty years. Now, as French power was reasserted, they were looked upon as a danger. All were arrested and deported, and scattered throughout the colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia. The largest group finally reached Louisiana. Their houses and barns in Acadia were destroyed and the country left empty. William Pitt became England’s first Prime Minster in 1757. His first move was to end the war in America with a massive attack by land and sea. His goals were the three bastions dominating access to Canada: Fort Ticonderoga guarding the land route to Quebec City; Fort Duquesne, the key to the Ohio country; and, most strategic of all, Louisbourg, blocking the St. Lawrence River, the supply line for all New France. Louisbourg had been greatly strengthened under the command of Chevalier de Drucour and was garrisoned by 4,000 soldiers and 2,600 seamen. The English force, under the command of Brigadier-General Jeffrey Amherst, gathered at Halifax and arrived off the Louisbourg coast on 2 June 1758. Held up by a storm, they waited six days before attempting the assault. Brigadier-General James Wolfe led the first body of troops ashore and was met by withering fire, losing many of his men before a beachhead was established. The siege lasted until 26 July, when the fortress surrendered, ending forever French military power in the Atlantic Provinces. Later in the year an expedition was sent out from Louisbourg to destroy any hostile Indian bands that had taken the French side in the recent conflict. They demolished only a single village and burned the Micmac church at Eskinwobudick, on Miramichi Bay, known today as Burnt Church. Submission of all the Indians was obtained. On 9 January 1760 Roger Morris and four other Indian leaders appeared before the legislative council to make peace on behalf of a large number of Micmacs. One band after another came to renew the agreements of 1725, culminating in a grand pow-wow in the governor’s garden in 1761. In the presence of assembled dignitaries they buried the hatchet and solemnly washed the symbolic warpaint from their bodies in token of a ‘peace that never should be broken’. It never has been.”

Note from Mary Lynn Smith: There were no deportations of Acadians to Louisiana. Acadians went to Louisiana of their own volition, from France.

Excerpt from Page 27

1763 to 1867: The Treaty of Paris to Confederation

“… With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, Ile St. Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Ile Royale (Cape Breton) were ceded to Britain. These were added to the administration developed in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick since the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. Prince Edward Island had an Indian population of 150, who had taken no part in the wars. They were Micmacs, but had not signed the ‘Articles of Submission and Agreement’ of 1725, neither had their compatriots on Cape Breton Island. There was now no need for separate negotiation, for a proclamation of King George confirmed hunting rights and protection of the Crown for all Indians in the former French possessions. With the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, serious attempts were made by the rebels to gain the help and affection of the Micmac and Malecite with gifts and promises. The Honourable Michael Francklin was appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and his main task was to maintain the loyalty of the Indians to the British cause. Representatives of the tribes were invited to Fort Howe, where a great council was held amid feasting and the giving of presents and medals. On 24 September 1778 a treaty was solemnly signed and the Indians all took oaths of allegiance. They gave gifts in return, both their own and those received from George Washington’s agents. With the influx of United Empire Loyalists during and after the American Revolution, Indian land rights in the Maritimes again were threatened. In 1773 the Executive Council of Nova Scotia issued a proclamation forbidding private persons to deal with or obtain lands from the original inhabitants. This was the beginning of the reserve and trust system that developed in the Atlantic Provinces. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century more and more of the Micmac and Malecite people began to settle on the reserves. At the same time there were many complaints of encroachment, due in part to incomplete surveys and boundaries that were ill-defined. In 1852 the Nova Scotia government enacted legislation for the purpose of taking title to all lands reserved for the exclusive use of Indians and to hold it in trust for them.”

Excerpt from Page 37

1763 to 1867

“… Article 40 of the terms for the Capitulation of Montreal reads; ‘The Indian Allies of His Most Christian Majesty shall be maintained in the lands they inhabit, if they choose to reside there, they shall not be molested on any pretence whatsoever, for having carried arms and served His Most Christian Majesty; they shall have, as well as the French, liberty of religion, and shall keep their missionaries’. During the French regime many of the Quebec Indians had become Christian and had settled on tracts of land granted by the government, the Church, or private persons. Even before the signing of the Peace of Paris and the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the population of the long-established settlements indicated their desire to remain on them and maintain their institutions … The British government, both in the New England states and in Acadia, had adopted the customs of distributing presents and food to the Indians. They continued this policy in Quebec to secure the goodwill of the King’s new subjects.”

From The Micmac Indians – The Kin-Friends of Cape Breton Published by Nova Scotia Tourism |

“… The French called these Indian people ‘Nikmaq’, meaning ‘my Kin-friends’. Eventually it became ‘Micmac’, the name by which these people are still known. The Micmacs were part of the Algonquin-speaking tribe and their people were trappers and fishermen. They lived in wigwams in communities ranging in size from 200 to 800 people. Their settlements were situated by the coast or by a river to facilitate trading with other communities. The Micmacs did not wage war among themselves. They followed a strict code of etiquette that kept the peace between the villages, and marriages between settlements were common, so one family would often be spread out over several villages. The Micmacs were a charitable and generous people. If one family had a surplus of food, they would give it to the village leader who would oversee distribution to the needy. In this way no one went without. Before the arrival of the Europeans and the fur trade, the Micmacs used whatever raw materials were at hand to make their clothes and tools. Tough animal hides were used to make moccasins and leggings, while softer hides were used to make clothing. The Micmac women would make decorative accessories of dyed porcupine quills intricately woven onto birch bark or cured animal hides. These amulets were thought to be status symbols as the wearer believed they would give him magic protection. Because of their skill in the art of quill weaving, another Indian tribe, the Malecite people, nicknamed the Micmacs the ‘Porcupine People’. Rituals were an important part of Micmac life, … Some were performed in preparation for a hunt, and the men would describe in dance the animals they sought and how they would capture them. Others would prepare the tribe for war. Still others would pass along stories from one generation to the next. One ritual performed by the women in the tribe described how medicinal herbs were discovered and used. The music performed at these occasions would be played on instruments made from a variety of things. Rattles were made of fish and skins stretched over a wooden frame with pebbles in the hollow. Whistles were carved from bones, and animal claws were strung together to make ‘dangles’. The Micmacs were also inventors of ‘Waltes’, a game played with six bone dice in a wooden bowl. The game is still played today. The Chapel Island Festival, in July, commemorates the conversion of the Micmacs to Roman Catholicism. Chapel Island was at one time considered a shrine to the Micmacs, who would come from miles around to be married or buried there. … the first Cape Bretoners were the Micmacs and their culture and influence survive to the present day.”

From A Monograph of Historic Sites in the Province of New Brunswick by W. F. Ganong |

Excerpt from Pages 13 to 15

Indian Routes of Travel in New Brunswick

“… The Indians of New Brunswick, like others of North America, were, within certain limits, great wanderers. For hunting, war, or treaty making, they passed incessantly not only throughout their own territory, but over that limit into the lands of other tribes. The Indian tribes of Acadia have never, within historic times, been at war with one another, but they joined in war against other tribes and mingled often with one another for that and other reasons. In facilities for such travel our Indians were extremely fortunate, for the Province is everywhere intersected by rivers readily navigable by their light canoes. Indeed, I doubt if anywhere else in the world is an equal extent of territory so completely watered by navigable streams, or whether in any other country canoe navigation was ever brought to such a pitch of perfection, or so exclusively relied upon for locomotion. The principal streams of the Province head together curiously in pairs, the country is almost invariably easy to travel between their sources, and a route may be found in almost any desired direction … But it was not only this fortunate arrangement of the rivers which made travel easy, but also the way in which the Indian adapted himself to it by the construction of his exquisite birch canoe, a craft which has excited the admiration of all writers from Champlain to our own day … Between the heads of the principal rivers were portage paths. Some of these are but a mile or two long – others longer … In New Brunswick the line of regular travel seems to have followed exclusively the rivers and the portage paths between their heads, and there is no evidence whatever of former extensive trails leading from one locality to another through the woods, … The birch canoe was the universal vehicle of locomotion in the New Brunswick Indian; it was to him what the pony is to the Indian of the West … When Portages are spoken of at this day they are usually given the name of the place towards which they lead; … Thus Bishop Plessis, in his journal of 1812, speaking of the portage between Tracadie and Tabusintac Rivers (the latter leading to Neguac) says: ‘We reached a portage of two miles which the people of Tracadie call the Nigauek Portage, and those of the Nigauek the Tracadie Portage’.”

From Savage Civilization Published by The New Brunswick Reader |

Excerpt from Pages 11 and 12

“… Pre-Loyalist Europeans were few in number, and dependent on their native neighbours, if not for military allies and actual help to survive, then at least for trade and tolerance to let them stay in prosperity and peace. A perusal of early treaties and accounts pertaining to what is now the Maritimes makes that relationship clear … ‘The reality of relations between aboriginal and European nations in these early periods was remarkably complex, fluid, and ambiguous’, says the Royal Commission report. ‘Thus, while the French for instance, clearly wanted to exert some form of sovereign control over neighbouring aboriginal peoples, they often had to settle for alliances or mere neutrality. And while aboriginal nations sometimes wished to assert their total independence of the French colony, in practice they often found themselves reliant on French trade and protection and increasingly overshadowed by European armed might’. Early in the 18th century the British and the Mi’kmaq fought a four-year out-and-out war, and there was a period of more than fifty years where Mi’kmaq raiders occasionally harassed settlers, and the settlers responded by paying bounties on scalps – a policy that seemed calculated to wipe the Mi’kmaq out … Whatever life was before and during the early days of contact, it changed dramatically and irrevocably as immigrants crowded the land. … A turning point was the Loyalist influx of the late 18th century – 40,000 people arriving all at once on the doorstep of what had been until then a wilderness society.”

From First People First Voices Edited by Penny Petrone |

Excerpt from the Jacket

“… ‘If old man come back, wouldn’t know this country; nothing same now; vessels sail about, steamboat make water dirty, and scare’em fish; Railroad and steam engine make noise, bustle, all change – this not Micmac Country – Micmac Country very quiet, no bustle; their Rivers make gentle murmur; trees sigh like young woman; everything beautiful’. Peter Paul, 1865

Excerpt from Page 32

Micmac Vengeance Song

Death I make singing,

Heh-yeh! heh-yeh! heh-yeh! heh-yeh!

Bones I hack, singing,

Heh-yeh! heh-yeh! heh-yeh! heh-yeh!

Death I make, singing,

Heh-yeh! heh-yeh! heh-yeh! heh-yeh!

Translated by Dr. Silas T. Rand

From Novwa’ Mkisk (Where the Sand Blows). |

Excerpt from Pages 44 and 45

“… Below is described the kind of knowledge of land and skies which allowed Micmacs to travel over great distances without the forms of transport or navigational tools needed by Europeans … especially does the Micmac know about Nova Scotia and the places adjacent. Show him a map of these places, and explain to him that it is ‘a picture of the country’, and although it may be the first time he has ever seen a map, he can go round it, and point out the different places with the utmost care. He is acquainted with every spot. He is in the habit of making rude drawings of places for the direction of others … Besides their accurate acquaintance with the face of the country, they are able to track you with all ease over the leaves in summer. They can discern the traces of your foot, where you can see nothing. … They have watched the stars during their night excursions, or while laying wait for game. They know that the North Star does not move, … They have observed that the circumpolar stars never set. They call the Great Bear, ‘Muen’ (the bear). And they have names for several other constellations.” Source: 1850 Silas Rand

Excerpts from Pages 74 to 80

“… The Micmacs traditionally lived as hunters, and that occupation ordered their world. Where and with whom they lived were determined by the seasonal patterns of animals and other resources … In the traditional belief system, many spirits and gods existed, possessing different types and levels of power. Souls of people, animals, and objects mixed with supernatural beings, good and evil, to form a supernatural world which existed alongside the natural one. After death souls traveled to another land, where good was rewarded and evil punished – then they were reincarnated. Shamans were the intermediaries between the gods and people. They could foresee the future, cure and cause illnesses and find game, often using animal spirits to help them. Aside from their powers, they were, in many ways, the law-givers in Micmac communities; by their powers and prestige they were able to maintain social and moral order. Soon after contact with the Europeans, the Micmacs adopted the Roman Catholic faith, and incorporated their traditional beliefs with the new in a unique version of Catholicism. The most venerated Saint for the Micmacs is Ste. Anne, mother of Mary. Her day, July 26th, is a time of great celebration, which used to bring Micmacs from Nova Scotia and Newfoundland together at Chapel Island each year … The Micmacs’ system of government was quite simple and egalitarian. Each band was governed by a chief chosen for his personal characteristics of fairness and bravery and for his family. … However, decisions were reached by a consensus of the village rather than by decree of the chief. Household heads comprised a sort of village council, with the chiefs of a number of villages comprising a regional council. The heads of regional councils met in district meetings when necessary, and the district chiefs and shamans comprised the Grand Council. Kinship structures were similarly loosely organized. The summer village, consisting of a number of extended families, was the largest social grouping. Families might include three or four generations, with young couples living with either set of parents or nearby on their own … The Micmac language was spoken by many into the early 20th century … making snowshoes or moccasins remain practiced skills for some people … the wigwams, or habitations of the Micmac Indians are constructed of birch-tree bark in a conical shape; and at the top there is an aperture for the smoke to escape through. They make their fires in the centre of the hut; and suspend deer flesh over it , to dry for the winter consumption … We also perceived great quantities of stinking fish and bones lying scattered about their wigwams, … In their persons they are robust and tall; with amazing coarse features, very high cheekbones, flattened noses, small eyes widely separated from each other, wide nostrils, and thick, black hair hanging perpendicularly from either temple. Source: 1818 Lieutenant E. Chappel – Voyage of HMS Rosamond to Newfoundland and the Southern Coast of Labrador … The wigwam is a curious structure … the fire occupies the centre. On each side is a kamigwom. There sit, on the one side of the fire, the master and mistress, and on the other, the old people, when there are old people in the family; and the young women when there are young women, and no old people. The wife has her place next to the door and by her side sits her lord. You will never see a woman setting above her husband – for towards the back part of the camp, the kutakumuk is up. This is the place of honour. To this place visitors and strangers, when received with a cordial welcome, are invited to come … The children are taught to respect their parents … they do not pass between their parents and the fire, unless there are old people, or strangers, on the opposite side … the men sit cross-legged, like the Orientals. The women sit with their feet twisted round to one side, one under the other. The younger children sit with their feet extended in front … There are usually a crowd of neighbours in every ‘camp’ at mealtime, when it is known that there is food there; and what there is, is divided among the whole. It may require a visit to several ‘camps’ in succession to obtain a full meal. Source: 1850 Silas Rand.”

Excerpts from Pages 86 to 92

“… The language of the Indians is very remarkable … It is flexible, copious and expressive … In its construction and idiom it differs widely from the English. This is why an Indian usually speaks such wretched English. He thinks in his own tongue and speaks in ours; and follows the natural order of his own arrangement … They have no r, f, or v. Instead of r they say l in such foreign words as they adopt. Source: 1850 Silas Rand … In some cases, the Indians we are describing prove excellent surgeons, particularly in their treatment of cuts, ulcers and bruises; but they have not the slightest idea of the means necessary to be pursued in setting a dislocated joint. The climate produces but few diseases, and they are consequently but little acquainted with remedies … * The following additional remarks concerning the Micmac Indians were communicated … by John Duke Esq – Surgeon of the HMS Rosamond … ‘I do not remember observing any acute or even chronic diseases amongst them. We were much struck at the care and tenderness evinced by the younger part of the community towards those, who, from infirmity or age, were rendered incapable of assisting themselves. I saw several instances of old persons unable to walk, and deprived of sight or hearing, who appeared to be regarded by he whole tribe as objects most worthy of their attention … Upon the whole, I am inclined to think that they enjoy, in general, excellent health’.

Source: 1818 Lieutenant E. Chappel … Micmac shamans – they acted as doctors, finders of game, and phropheciers … when sick, they send … a conjurer, who prays to the devils, blows upon the party, cuts him and sucks the blood; he heals wounds in the same manner, applying a round slice of beaver stores, for which they present him with venison or skins. Source: 1839 Ephraim Tucker – Five Months In Labrador and Newfoundland … The Micmacs are, in their dispositions, naturally good-natured, and exceedingly civil towards strangers; but when intoxicated, their whole manner changes. Spirituous liquors, of which they are exceedingly fond, will in an instant, convert a peaceful and inoffensive Indian, into a most ferocious savage. The women and children are then compelled to seek refuge in the woods. The barbarian, not finding any person on whom he dare wreak his brutal vengeance, will attack his own wretched wigwam, break every article it contains, and probably complete the wreck by tearing the whole fabric to the ground; nay even the barrel of his musket is frequently bent double, and the stock broken in pieces … If this infuriate maniac be visited on the following morning, he will be found sitting on the ground, with his family around him, lamenting, in bitter terms, the effects of his preceding debauch … One of the Indians visiting the Rosamond … was requested to exhibit his skill as a marksman … Accordingly, he went to the arm-chest to select a musket for the purpose … At length, taking up a marine’s firelock, he held it to his eye, to see if it were perfectly straight, then, shaking his head, he took the barrel out of the stock, and repeatedly bent it, in different directions, over his knee; afterwards, he replaced it in the stock, and then, walking forward with a confident air., he leveled the piece, and , in an instant, shivered the bottle to atoms … Murders are very uncommon amongst this people; but broken heads, loss of eyes, and deep cuts, are frequently inflicted during their drunken quarrels … although they may be incapable in revenging a deliberate insult, yet they have never been known to resent the provocations of an intoxicated man. ‘Should we blame or punish him’, say they, ‘when he does not know what he is about, or has not his reason?’ Source: 1818 Lieutenant E Chappel.”

From The Old Man Told Us – Excerpts from Micmac History 1500 – 1950 by Ruth Holmes Whitehead |

Excerpt from the Introduction

“… until some time in the 20th century, most Micmac did not speak fluent French or English … The Micmac people have been living in the land now called Atlantic Canada for at least 2,000 years or more.”

Excerpt from Page 50

1650

“… Tabasintak (Tabusintac) is the place pointed out on the map by Ben Brooks as the identical spot (where Mejilapeka’tasiek killed Wohooweh). He has been there and seen the rock on which tradition says the Kwedech’s head was smashed; it lies about in the centre of the sand-bar that stretches along in front of the mouth of the river, outside of the lagoon … The stone … is of a singular form – hollow on the top, like a dish; and from this stone, and the circumstance related, the place has ever since borne the name Batkwedagunuchk, which no English word can easily translate. It indicates very poetically that on this rock a fellow’s head was split; an anvil comes nearest to it. My informant has not seen the rock since he was a small boy; but the form, and the associations connected with it are indelibly fixed upon his memory.”

Source: From Silas Rand Legends of the Micmacs 1894

Excerpt from Page 61

1675 – 1683

“… Our poor Indian women have so much affection for their children that they do not rate the quality of nurse any lower than that of mother. They ever suckle the children up to the age of four or five years, and when these begin to eat, the mothers chew the meat in order to induce the children to swallow it. One cannot express the tenderness and affection which the fathers and mothers have for their children … An Indian woman, when in a canoe one day, feeling herself pressed by the pains of childbirth, asked those of her company to put her on shore, and to wait for her a moment. She entered alone into the woods, where she was delivered of a boy; she brought him to the canoe, which she helped to paddle all the rest of the journey.”

Source: Christien LeClercq New Relation of Gaspesia 1968

Excerpt from Page 75

1699

” … These wretched people are very liable to be drowned; it happens only too frequently, because their bark canoes capsize at the slightest provocation. Those who were fortunate enough to escape from the wreck made haste to rescue those who remain in the water. They then fill with tobacco smoke the bladder of some animals, or a long section of large bowel, commonly used as receptacles for the preservation of their fish and seal oil, and having tied one end securely, they fasten a piece of pipe or calumet into the other, to serve as an injection tube; this is introduced into the backside of the men who have been drowned, and by compressing it with their hands, they force into them the smoke contained in the bowel – they are afterwards tied by the feet to the nearest tree which can be found, and kept under observation; almost always follows the satisfaction of seeing that the Smoke Douche forces them to disgorge all the water they had swallowed. Life is restored to their bodies, and before long this astonishing and beneficent result is made manifest by the twitching movements of the suspended men.”

Source: Le Sieur de Diereville Relation of the Voyage to Port Royal in Acadia 1968

Excerpt from Page 77

1700 – 1799

” … By 1761, ‘tired of a war that destroyed many of our people’, the Micmac negotiated a truce with the English. But the great numbers of Loyalist settlers, fleeing the American Revolution, made vast inroads on traditional Micmac lands. Game was no longer plentiful; salmon rivers were blocked by dams and choked with sawdust. The fur trade was in decline and smallpox epidemics swept the Maritimes. The Micmac, their 17th century population already reduced by 90 percent, were particularly hard hit. This period was the seal of despair on traditional Micmac life, …”

Excerpt from page 98

1737

“… This nation counts its years by the winters. When they ask a man how old he is, they say, ‘How many winters have gone over thy head’? Their months are lunar, and they calculate their time by them. When we would say, ‘I shall be six weeks on my journey’, they express it by, ‘I shall be a moon and a half on it’.”

Source: Pierre Antoine Simon Maillard An Account of the Customs and Manners of the Mikmakis and Maricheets, Savage Nations, Now Dependent on the Government at Cape Breton 1758

Excerpt from Page 115

1749

“… At a Council held on board the Beauport on Sunday the 1st October 1749. Present: His Excellency the Governor, John Horseman, John Gorham, Charles Lawrence, Benjamin Green, Edward How, John Salusbury, Hugh Davidson, Esqrs. That a premium be promised of Ten Guineas for every Indian killed or Taken prisoner. That Mr. William Clapham be directed to raise a Company of Volunteers in this settlement who may scout the country around the Bay, who shall have the same pay and provisions as the Troops here and reward of Ten Guineas for every Indian they shall take or destroy.”

Source: Gustave Lanctot Documents Relating to Currency, Exchange and Finance in Nova Scotia 1675-1758 1933

Excerpt from page 122

1751

“… this is attributed to the care of the Indians for heir dead, as they always carry their fallen comrades with them when retiring from a scene of slaughter.”

Excerpt from Page 141

1755

“… I learned that, at the village of (Tatamagouche) there are 20 Indians fit to bear arms, … at Baye de Chaleurs, 120; at (Richibucto) 17; at Miramichi, 150; near Baye de Chaleurs, 120.”

Excerpt from Pages 144 and 145

1755

“… September 5th saw here a tragic site. It stands out darkly in our history. The Masstown beach was thronged with weeping women and children … The men were herded onto the (English) ship. Later in the day the women and children, all except two women who had escaped, were placed on a separate ship … One of the women who had been left behind returned that night to her home, which was still standing. In her arms she carried her babe … Presently an Indian came to her. She enquired as to the fate of her people. ‘Gone’, he said. ‘All gone! People everywhere prisoner. See smoke rise! They burn all here tonight’. The Indian spoke only too truly, for blazing fires in the distance attested the truth of his words. He helped the woman to gather some of her most valuable things that were left, hen piloted her to his wigwam. Here she found about a dozen of her people – all who were left … The party waited more than a month to see if any others would be found. Then they set forth for Miramichi.”

Source: Clara Dennis More About Nova Scotia

Excerpt from Pages 151 and 152

1759

“… The Indians … often harassed the English settlements in various parts of the Province. Consequently, the Government raised Volunteers to hunt down the Aborigines, offering a premium of twenty-five Pounds for any male Indian prisoner above sixteen years old; twenty Pounds for each female prisoner, the same price for a man’s scalp; and ten Pounds for every child prisoner. These Volunteer Companies were placed under the command of Colonel Scott and Major Samuel Rogers, afterwards Representative of Sackville in the House of Assembly.”

Source: Abraham Gesner New Brunswick with Notes for Emigrants 1847

Excerpt from Page 155

1761

“… Treaty of Peace and Friendship concluded by the Honourable Jonathan Belcher Esquire, President of His Majesty’s Council and Commander in Chief in and over His Majesty’s Province of Nova Scotia or Acadia etc etc with Joseph Shabecholouest of the Merimichi Tribe of Micmac Indians at Halifax in the Province of Nova Scotia or Acadia … Joseph Shabecholouest (sic) His Max (mark).

Source: Selections from the Public Documents of the Province of Nova Scotia edited by Thomas Akins 1869

Excerpt from Pages 164 and 165

1761

“… Wednesday, November 18. Last night proved a cold, dry night – the weather moderate – went back the way we came to our canoe, where we had left our baggage – arrived there about twelve o’clock, and wet as I was, immediately embarked, and with a fair wind reached Merrimichi about six o’clock. I was obliged to be carried out of the canoe into a hut, to warm and dry myself; for I had almost lost the use of my limbs with sitting steady in a bark canoe six hours, wet up to the middle. Friday, November 20. The chief of the Indians (Louis Francois, Miramichi) came to me – shewed his treaty with he Governor of Halifax, and said he would conduct me to Fort Cumberland. Saturday, November 21. The Indians here are about fifty fighting men – they are all the Merrimichi tribe of Mickmacs. Saturday, December 5. Left our canoe, and went up the creek about a mile; crossed a small river upon the ice, to a deserted house of the French – we found the Indians had been there, but they were gone up the river a hunting – we found the head of a dog smoked whole, the hair singed off, but the teeth and tongue standing – The Indians, when they make a great feast, kill two or three dogs, which they hold as a high treat – at such times they have a grand dance.”

Source: Gamaliel Smethurst A Narrative of an Extraordinary Escape out of the Hands of the Indians in the Gulph of St. Lawrence 1774

Excerpt from Pages 172 and 173

1777 (See Note below by Mary Lynn Smith)

“… (During the American Revolution) the Indians were holding a Grand Council at Bartibog Island, and had resolved upon the death of every individual belonging to the infant (New Brunswick) settlement. While the Council was sitting … The Viper sloop-of-war, commanded by Captain Harvey, appeared in the Bay. She had captured the American Privateer Lafayette, and in order to decoy the savages, she was sent up the river under American colours. But the Indians were too chary to be deceived by this stratagem, and, by assuming the character of pirates, they resolved to make a prize of the vessel. Upwards of thirty of them were allowed to come on board. After a desperate struggle, they were overpowered; and such as were not killed in the affray were put in irons. Among those desperadoes was one named Pierre Martin, whose strength and savage courage were truly characteristic of his tribe. Two marines were unable to bind him, and he nearly strangled two others with whom he was engaged. After he had received several severe wounds, he tore a bayonet from the hands of a sailor, and missing his thrust at one of his opponents, he drove the weapon through one of the stanchions of the vessel. Covered with wounds, the savage at last fell, as was supposed to rise no more; but even in his dying moments, when his flesh was quivering under deep sabre-cuts, and his body was bathed in blood, he sprang to his feet, and fastened himself upon the throat of one of his companions, upbraiding him with cowardice. He had almost strangled the trembling Indian, when he was despatched by one of the crew. The wretches thus taken were sent to Quebec, and nine of them were afterwards put on board a vessel bound to Halifax. On her passage the vessel engaged an American privateer. Étienne Bamaly?, one of the prisoners, requested leave to fight for King George. Permission was given him – his irons were removed, a musket put in his hands, and he killed at two different times the helmsman of the American cruiser. The English gained the victory; and when the prize was brought to Halifax, Bamaly was liberated on account of his bravery. Of sixteen Indians carried away, only six ever returned to Miramichi.”

Source: Abraham Gesner 1847

Note from Mary Lynn Smith: The date of this event was 1779 in the month of July. On the 8th day of that month an “Account (unsigned) by Capt. Hervey, of the “Viper,” of the proceedings with the Indians at Miramichi, their conduct towards the inhabitants; capture of the chiefs, etc.) was tabled. Reference: Sessional Papers of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada, Vol. 21, Issue 5. Canada/Parliament Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty. Sessional Papers (No. 4A) Haldimand Collection 1888 Canada. Report of Indian Meetings, Treaties, etc. – 1778-1784. Page 59.

Excerpt from Pages 175 and 176

1782

“… Those (Micmac) that I have seen were a tall, beautiful, sinewy kind of people, with longish regular features like the original Brandenburgers. I don’t remember having seen anyone taller than 5’9″ or shorter than 5’3″. … Normally they came (into Halifax) by sea, in their birchbark boats, which were masterfully built, and which they knew how to guide superbly with their little paddles … They made long voyages along the coast in these boats, and go out to sea in them for extraordinary distances.”

Source: Johan Seume Mein Leben 1961 (Seume was a corporal in the Hessian contingent of the British Army, and was stationed in Halifax between 1782 and 1784).

Excerpt from Page 177

1785

“… The three mentions of burials we have found in parish registers of the colony pose a morbid question. The 21st of April the Indians brought with them the body of a certain Jacques, who had died in Newfoundland the 15th of February previous; the 12th September of the same year, there was buried at Saint-Pierre, the body of Marie, widow of Andre, who had died in Newfoundland, aged 91 years, four months earlier; and the next year, on the 6th of September, the Indians brought the body of Anne Etiennchuit, widow of Andre Gougou, who had also died in Newfoundland, the preceding 25th of May. How was it that the Micmac could conserve the bodies of their dead for such a long time? It is probable they used a technique similar to that of drying fish, preserving the bodies in salt.”

Source: Jean Yves Ribault Les Iles Saint-Pierre et Miquelon 1968

Excerpt from Page 178

1790

“… The moose and cariboo … are the principal animals; the former now comparatively scarce, owing to an indiscriminate massacre which took place for the sake of the hides, soon after the English settled in the country. So murderous was the destruction of his fine animal, that hundreds of carcasses were left scattered along the shore from St. Ann’s to Cape North; the stench from which was so great, as to be wafted from the shore to vessels at a considerable distance at sea.”

Source: R. Montgomery Martin A History of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton 1837

Excerpt from Page 178

1791

“… Walking in one of the streets I observed an Indian canoe, which had been conveyed thither from the water; it was between 18 and 20 feet in length and measured 2 feet 8 inches across in the broadest part … The company which came in this boat consisted of three women, a boy about 15 years old, and an infant at the breast as I saw them in the street. I desired them to follow me home. The women were somewhat low in stature and all of them had a yellowish or copper coloured complexion with long straight black hair – Their dress consisted of a flowered woolen jacket reaching to the waist and a coarse blue short petticoat, a cap made of cloth angular to the upper and back part of the head, and ornamented with small white beads; round their neck, they likewise wore several strings of different coloured beads to which was affixed a silver cross. The boy had on a coarse blue jacket and canvas trousers. What little these Indians understood of the English language was spoken with a very drawling accent, they appeared well acquainted with the value of each article they bought (cranberries and wild fowl) singly, but when they sold several at the price they required they were entirely at a loss in what manner to calculate the amount or sum total – In this respect, therefore, they were wholly at the mercy of the whites, who might readily have cheated them with impunity and without fear of detection, seeing that these poor Indians implicitly relied on their honesty – I am afraid there are many in this Province who take every advantage of them. I offered these Indians each a glass of spirits which I imagined they were fond of, but they rejected it with marks of abhorrence, giving me to understand that they could eat bread or biscuit. … I understood they had left their wigwams this morning and intended returning immediately. Their residence therefore could not be a great distance from Halifax.”

Source: J. Clarkson Clarkson’s Mission to America 1791 – 1792

Excerpt from Pages 179 and 180

1791

“… Then setting out pretty early, we set up sails in both canoes, and alternately sailed, poled and paddled … Many more streams, falling into the river below the Kain’s (Cain’s River, New Brunswick) than above, heightened the prospect all along, till we arrived at the point where the river Renow (Renous) falls into the Merimashee (Miramichi) on the north side. Here we saw an Indian and his sqa making some small, but very neat baskets of Porcupine quills of various colours. Their method of dying the quills is as follows: They pick up small pieces of cloth of every colour they can find. These they scrape down as small as they can, and boil separately in kettles, till the dye is extracted from the wool; then put in the quills in them. This dyes them, and gives them as fine colours as can be wished; indeed I never saw more brilliant … Having encamped and slept all night on the banks of the (Restigouche) river, we set out pretty early next morning, and … I observed two wigwams; I went in to see them, and found them both without an inhabitant. The families had been then either fishing or hunting. The furniture of these temporary habitations consisted of several dishes made of birch bark, finely ornamented, and boxes of Porcupine quills, as I supposed for sale. Besides these, I saw a root drying, which the Indians use as a cure for many complaints, and took a piece of it along with me. The name they give it, I think, is Calomet (Acorus Calamus, sweet flag). It has a strong, spicy taste, an aromatic scent, and heats the stomach almost as much as a dram.”

Source: Patrick Campbell Travels in North America

Excerpt from Page 183

1800 – 1899

“… At the beginning of the nineteenth century, population figures for the Micmac were so low that it was expected that they would soon follow the Beothuk Indians into extinction. Various governmental and philanthropic groups had hopes of establishing the People in the practice of agriculture … An auspicious start to the farming communities thus set up was doomed when in 1844 the potato blight appeared – the same blight which caused the Irish Famine. For at least three years, this disease, the ‘poison wind’, raged. In two of those years, wet weather ruined the hay and grain crops also, and this in turn affected the livestock. A wheat weevil and a drought were the last straws, and the Micmac were forced back into whatever diminished subsistence the forests could provide, and a life of roaming from place to place, selling or bartering baskets, axe handles, butter churns and other works of their hands. Borderline starvation was the rule. Tuberculosis and other diseases reaped their own harvests. Infant mortality was extraordinarily high – single families often lost 12 or more of their offspring. But the 1800s also saw – perhaps as a result of Chief Louis-Benjamin Peminuit Paul’s appeal to Queen Victoria – the beginnings of some sense of compassion on the part of the colonial government. Now the setting aside of reserve lands was begun, and the creation of Indian agencies to provide financial and medical relief, and – at least in theory – legal recourse for the Micmac people.”

Excerpt from Page 198

1825

“… The present Indians of Nova Scotia are all one nation, known by the name of Micmacs, and were among other natives the original inhabitants of the country. They are by no means numerous, and are fast diminishing in numbers, as they wander, like those of New Brunswick, in extreme wretchedness, and detached parties, throughout the Province.”

Excerpt from Pages 208 and 209

1832

“.. If a highly polished language be a mark of no ordinary mental qualities, then well may the Micmac boast of his … If we consider the variety of their verbs – the regularity of their various shades of difference – the number of moods and tenses – the utmost infinite number of terminations – the beautiful manner of forming complex ideas by compounding different words – the melody of the language – all shew that they were minds of no common cast who framed it, or who now use it. Indeed it is not before the age of 30 or 35 that men attain a complete knowledge of it, and females seldom or never.”

Source: Thomas Irwin in The Nova Scotian, Halifax, 5 September, 1832 (Irwin contradicts the Abbe Maillard, who said that old women spoke the best Micmac)

Excerpt from Pages 217 and 218

1840

“… About the last of March or the first of April (one winter), the Indians had very few provisions – there was no game or fish. A big storm came. (Peter Ginnish’s) grandfather heard a crow flying toward him. It came close to him, then cawed and cawed. He noticed it appeared to be greasy, and was wiping and cleaning its bill on its feathers. It cawed and cawed, then flew off to one end of Portage Island. He told his father about the crow. They went out with another man, put on their snowshoes, and crossed on the ice to the island. Something had come ashore. When they arrived at the place, they found it to be something large, like a ship, and black. It was a big whale. They found a big whale! There was seven inches of fat in addition to the meaty part. The men returned, each with a big load. Next morning a man went on snowshoes to Richibucto, one to Red Bank, one to Shippigan, and even to Bathurst and Restigouche, to take the news. From all these settlements the Indians came and hauled away pieces of the whale – every piece of it. They left only the bones. The Indians are never stingy. They are like a crow. It is never stingy. When a crow finds provisions, it brings the news to the Indians. It came to tell the people at Burnt Church about the whale which it had found at Portage Island.”

Source: Peter Ginnish to Wilson D. Wallis 1911

Excerpt from Page 237

1848

“… Almost the whole Micmac population are now vagrants, who wander from place to place, and door to door, seeking alms. The aged and infirm are supplied with written briefs upon which they place much reliance. They are clad in filthy rags. Necessity often compels them to consume putrid and unwholesome food. The offal of the slaughterhouse is their share. Their camps or wigwams are seldom comfortable and in winter, at places where they are not permitted to cut wood, they suffer from the cold.”

Excerpt from Pages 239 to 241

1849

“… To His Excellency John Harvey, K.C.R. and K.H.H.. Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia:

The Petition of the undersigned Chiefs and Captains of the Micmac Indians of Nova Scotia, for and on behalf of themselves and their tribe humbly showeth:

That a long time ago our fathers owned and occupied all the lands called Nova Scotia, our people lived upon the sides of the rivers and were a great many. We were strong but you were stronger, and we were conquered. Tired of a war that destroyed many of our people, almost 90 years ago our Chief made peace and buried the hatchet forever. When that peace was made, the English Governor promised us protection, as much land as we wanted, and the preservation of our fisheries and game. These we now very much want. Before the white people came, we had plenty of wild roots, plenty of fish, and plenty of corn. The skins of the moose and the cariboo were warm to our bodies, we had plenty of good land, we worshipped ‘Kesoult’ the Great Spirit, we were free and we were happy.

Good and Honourable Governor, be not offended at what we say, for we wish to please you. But your people had not land enough, they came and killed many of our tribe and took from us our country. You have taken from us our lands and trees and have destroyed our game. The Moose yards of our fathers, where are they? White men kill the moose and leave the meat in the woods. You have put ships and steamboats upon the waters and they scare away the fish. You have made dams across the rivers so that the salmon cannot group, and your laws will not permit us to spear them. In old times our wigwams stood in the pleasant places along the sides of the rivers. These places are now taken from us, and we are told to go away. Upon our camping grounds you have built towns, and the graves of our fathers are broken by the plow and harrow. Even the ash and maple are growing scarce. We are told to cut no trees upon the farmer’s ground, and the land you have given us is taken away every year.

Before you came we had no sickness, our old men were wise, and our young men were strong, now smallpox, measles and fevers destroy our tribe. The rum sold them makes them drunk, and they perish, and they learn wickedness our old people never heard of. Surely we obey your laws, your cattle are safe upon the hills and in the woods. When your children are lost do we not go to look for them? The whole of our people in Nova Scotia is about 1500. Of that number 106 died in 1846 and the number of deaths in 1848 was, we believe, 94. We have never been in worse condition than now. We suffer for clothes and victuals … Our nation is like a withering leaf in a summer’s sun … what more can we say? We will ask our Mother the Queen to help us. We beg your Excellency to help us in our distress, and help us that we may at least be able to help ourselves. And your petitioners as in duty bound will ever pray:

Pelancea Paul His mark a cross

Colum Paul His mark a pipe

Piel Toney His mark a sun

Louis Paul His mark a heart, etc., …”

Source: Abraham Gesner at Chebucto, 8 February 1840 Published in the Acadian Recorder, 1849

Excerpt from Pages 241 to 243

1849

“… A number of Indians have lately come to Charlottetown from Shediac and Miramichi, among whom is a venerable old chief named Joseph Nokut, who has been entertained and feasted by the Indians residing there … They bring dismal intelligence respecting a fearful mortality lately at a place called Napan, near Miramichi. In some cases, whole families were cut off : 34 died in all, and they are under the apprehension that they were poisoned, and that it was done intentionally by the whites. They are a good deal excited about it. I have just begun questioning the old Chief respecting the affair. He says that on New Year’s Day last, according to custom, that Indians went round, firing salutes, and wishing people a happy New Year; that they received presents as usual, and among the rest a quantity of flour and butter; that those who ate of it, were immediately seized with sickness and died. Two young men fled and went as far as Amherst, where one of them was taken sick in the same way as the rest had been, and the other brought a doctor to him. The Indian died, and was examined by the doctor, who stated that he had taken poison. The other Indian immediately spread the intelligence among his comrades. The news was brought to this place, more than a month ago by two Indians, who seem to have come over for that purpose.”

Source: The Nova Scotian Halifax 30 July 1849

Excerpt from Page 245

1851

“… No nation pays more attention to the remains of their ancestors – they wrap them with the choicest furs, and preserve them with affectionate veneration. Some years ago, a young Indian died very near me, when most of the men were from home on a hunting expedition. His family applied to us for assistance in burying their dead – at once we offered them linen, and boards to make a coffin, and the choice of our burial ground; they accepted the boards and the linen, but the ground was of no use, it was not consecrated. The poor creatures mustered what strength they could, and carried away the young man to the resting place of his ancestors, nearly 30 miles, and the melancholy train of that funeral would have made an impression on the stoutest hearts.”

Source: The Nova Scotian Halifax 30 June 1851

From Indian Lands in New Brunswick: The Case of the Little South West Reserve by W. D. Hamilton |

Excerpts from Pages 1 to 9

“… The history of Indian lands in New Brunswick is complicated by the fact that no land treaties as such were concluded between the Indians and the government – either before the province was formed in 1784, or afterwards … In these early treaties and proclamations, however, the boundaries of the lands which the Indians had an acknowledged right to occupy were not indicated. The first descriptions of boundaries were those given in the licences of occupation which were issued to the Indians from the 1770s onward. This method of licencing land for the Indians’ use stood in contrast to the system of seigneurial grants used in New France and the treaty arrangements made later in other parts of Canada. A licence of occupation was not a grant in fee simple but a licence to occupy and possess during the pleasure of the crown; the land remained crown land and was not to be sold or otherwise alienated by the Indians … the rights of the Indians were seriously threatened in 1765 when a 100,000-acre township grant was made on the Miramichi to William Davidson and John Cort. Davidson and Cort were about to establish a commercial fishery that would interfere with one of the means of livelihood of the Indians residing along the North and South West branches of the river. Furthermore, their grant actually embraced the Indian village sites along these branches, including the ancient Red Bank site at the mouth of the Little South West. It is not known to what extent the Indians at first comprehended the implications of Davidson and Cort’s incursion into the interior of the Miramichi river system. Neither is it known if resentment of Davidson and Cort’s enterprise there contributed to the Micmacs’ disaffection from the English cause in the Revolutionary War years or to their effective routing of Davidson and most of his followers from the grant in 1777. Davidson is mute on the subject in his correspondence, but he was convinced that the Indians had solemnly resolved to massacre those of his settlers who did not flee the grant with him, and that they would have done so if the sloop of war Viper had not come into Miramichi Bay at a critical moment in the summer of 1777 – and put up the river to confront and intimidate a dangerously restive Indian population. In his account of this episode, Robert Cooney states that throughout the period of Indian unrest on the river associated with the Revolutionary War the Julian tribe, or family, of Micmac Indians distinguished themselves by their moderation and by the protection which they extended to the settlers. ‘They not only conducted themselves with exemplary forbearance’, he wrote, ‘but even frequently interposed their influence in behalf of the people’. This version of the Julians’ role in the conflict is corroborated in a letter written by Alexander Taylor, an early Northumberland County magistrate. Moses Perley, in an unpublished narrative of events relating to the Indians of New Brunswick, cites other pertinent facts. He states that the Viper was sent to the river during this period for the protection of the settlers, and that the Indians, at the same time, were severely chastised for their riotousness. According to Perley, the Micmac chief, Caiffe (or Cive), fled and was proclaimed a rebel, and on 20 July 1779, a treaty of peace was concluded between Captain Augustus Harvey, of the Viper, and John Julian, who was then declared Chief of the Miramichi Indians. At the conclusion of the hostilities, in what was regarded as a reward for their loyalty and assistance, ‘John Julian and his tribe’ were granted a licence of occupation by John Parr, Governor of Nova Scotia, to a 20,000-acre tract of land lying along either side of the North West branch of the Miramichi. This tract extended from a point below the mouth of the Little South West branch, past the mouth of the Sevogle River and other tributaries of the North West … the tract granted by the Parr Licence overlapled Davidson and Cort’s grant on both the North West and Little South West branches. When John and Francis Julian attempted to exact payment in 1785 from Davidson’s tenants for hay cut on the wild meadows inside their line, they learned from Northumberland County Sheriff Benjamin Marston that Davidson’s claim took precedence over their own. ‘I have told the chiefs’, wrote Marston to the Provincial Secretary, ‘that these meadows were given away a great while ago by the Governor of Halifax to Davidson and Cort, but this to a Savage is a very strange thing. That one Governor of Halifax should give away land which another Governor before him had already given away to another man. But a little acquaintance with Governor Parr would have informed him that His Excellency often did so by land which he had himself already given away to another’. Marston consoled the Julians by informing them that Davidson and Cort’s grant would probably be revoked because of their failure to fulfil its conditions … Davidson’s grant was revoked in 1786, but the Indians did not immediately benefit from this. On the contrary, in the early 1790s, the most valuable land along the North West branch of the river which they claimed by virtue of the Parr Licence was granted to Loyalists and other settlers, and the Indians soon found themselves struggling to retain possession of even the village site of Red Bank … a dispute between the Julians and Duffy Gillice, a resident on one of Davidson’s lots, smouldered throughout the 1790s. Previously, Gillice had farmed an interval within the village with the Indians’ consent. But when he attempted to acquire title to the old Micmac burial site as a location from which to net salmon, the Indians were indignant. Alexander Taylor, after sending an observer to inspect the place in dispute, expressed the opinion that a great injustice was being done the Indians by Gillice and some of his neighbours. ‘If you think it proper’, he wrote Colonel Edward Winslow, ‘to have His Excellency informed of it I do actually think it would be a great charity, because the very road to justice seems to be entangled against these poor creatures, and I’m sure that’s not His Excellency’s will’ … Odell invited Gillice to ‘relinquish that part at least of the lot which is claimed by the Indians and discontinue the setting of the cross net, or else show cause without loss of time to His Excellency in Council why the lot should not be granted to the Indians. By order-in-council dated 5 February 1802, the parcel of land in question was secured to the Indians, the Duffy Gillice affair may have helped alert Fredericton authorities to the need to have the land claims of the Miramichi Indians located, surveyed, and licenced.”

Note from Mary Lynn Smith: The date of this event was 1779 in the month of July. On the 8th day of that month an “Account (unsigned) by Capt. Hervey, of the “Viper,” of the proceedings with the Indians at Miramichi, their conduct towards the inhabitants; capture of the chiefs, etc.) was tabled. Reference: Sessional Papers of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada, Vol. 21, Issue 5. Canada/Parliament Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty. Sessional Papers (No. 4A) Haldimand Collection 1888 Canada. Report of Indian Meetings, Treaties, etc. – 1778-1784. Page 59.

From PANB – Daniel Johnson’s Newspapers Vol 26 No 2096 Rank 44

July 18, 1868 SJ SJ The Morning Freeman

Nicola JULIAN, Chief of the MicMac tribe of Indians residing on the Miramichi waters died Thursday last at Edgeground, Northesk (North Co.). age 90 years, 30 of which he was Chief. He has left behind him 3 sons and a progeny of grandchildren. When Quebec was taken by General Wolfe , the MicMac Indians residing on the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Straits of Northumberland were divided in their sympathies and allegiance – some adhering to the fortunes of France and others contending for the Sovereignty of Great Britain. Among the latter, the families of JULIAN and GONISHE bore a conspicuous part; and from the JULIAN branch the deceased was an immediate descendant; and whose ancestor, Andrew JULIAN for many years was chief prior to Nicola. For his loyalty and attachment to the British Crown, he received from George III a distinguished mark of Royal approbation – Com. to ‘Advocate’.