BLACK WATCH

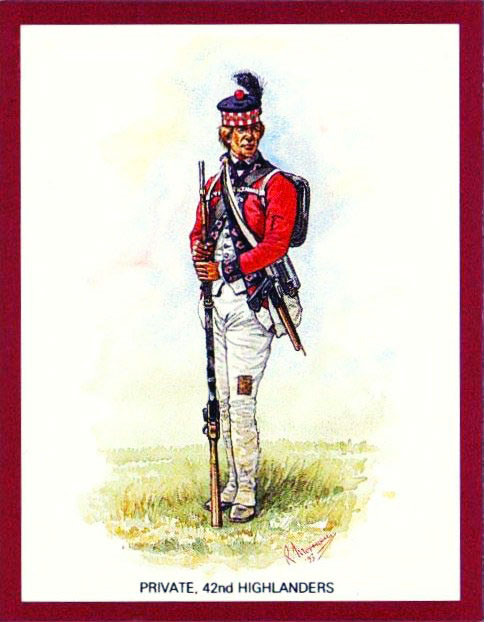

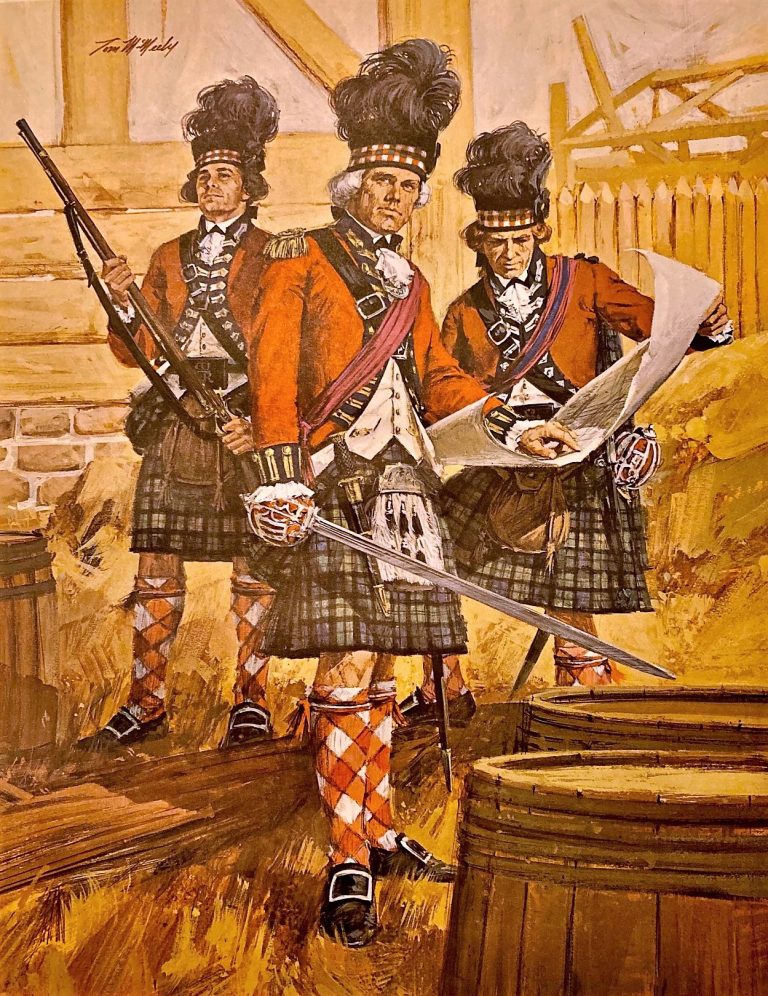

42nd highlander regiment

The Black Watch

From The 42nd Royal Highland Regiment, The Black Watch (Nashwaak) by Margaret Pugh |

Excerpt from Pages 69 to 71

“… The 42nd Royal Highland Regiment, often referred to as ‘The Black Watch’, grew from independent companies formed to police the Scottish highlands. Such policing was necessary since there was much discontent and unrest in Scotland after the Union of the Parliaments of England and Scotland in 1707. The highlanders were members of clans ruled by clan chiefs. There were occasions in the highlands when one clan would attack another clan and times when raiding parties went outside the highland … By the year 1730, the independent companies were formed. They were made up of all highlanders and were given the name ‘The Black Watch’. The name ‘Black Watch’ is derived from the colours in the tartan which they wore. The colours were mostly black, blue and green, a contrast to the ‘Red Coats’ whom they disliked. The word ‘Watch’ was used due to the fact that their duty was to watch over the highlands. The regimental tartan was a twelve-yard length of cloth which was wrapped about the waists and looped over the left shoulder. A white vest was worn and a white goatskin sporran (a tasseled pouch hanging in front of their kilt) and low, checkered highland bonnets not unlike berets. In 1740 they were mustered into a regiment with the number 43, later they received the number 42. Joining the army was very attractive to the highlanders; their country at that time offered them no professions while the army guaranteed a steady income. The Disarmament Act made it illegal for a highlander who was not enlisted to wear a kilt or bear arms. In the early days of the regiment the recruits did not have to leave home to take advantage of all the army had to offer because they served locally. As time went on they became a very proud and loyal regiment … In 1776, they proudly joined the regiment knowing it was going to America. Some had just returned from serving in Ireland. Thomas Fraser was one of these. The 42nd Royal Highland Regiment was a special regiment, with its native dress and speaking their peculiar Gaelic dialect.

The Black Watch left Greenoch, Scotland May 1, 1776, along with the Fraser Highlanders. During the crossing of the Atlantic the convoy was attacked by privateers. One of the ships, ‘The Oxford’, after a struggle with the privateers, became separated from the convoy and landed in Jamestown, Virginia. The Revolutionary War was on at the time and Jamestown was controlled by the rebels. The highlanders were offered land if they would join the rebel cause but they remained loyal to the King and were taken prisoners. They were released two years later and rejoined the regiment. The other transports crossed the Atlantic safely and reached Staten Island on August 3, 1776. The Black Watch fought throughout the war and were victorious in many battles. They fought at Bloomingdale, Long Island in 1776, shortly after they landed in America. Later they captured White Plains and Brooklyn and by November 1776, they had control of Fort Washington. In May 1777, they were successful at Pisquata … In September they were victorious at Brandywine and Paoli. It was at Paoli where they attacked the Americans ‘with bayonet alone’. In October 1777 the Black Watch won the battle of Germantown which gave the British control of the colonial capital of Philadelphia. Meanwhile, General Washington moved his troops to Valley Forge for the winter. The highlanders were also victorious at Freehold in June 1778, when the British were retreating to New York. In the spring of 1780 they took part in the siege of Charleston, South Carolina, until its surrender May 12th. They returned to New York and were encamped in various places. They were in the convoy of ships that was to relieve General Cornwallis at Yorktown in October 1781. By the time they arrived Cornwallis had surrendered. They returned to New York with General Clinton, the commander of the British Army and remained stationed in this area for the remainder of the war.

Approximately one hundred men of the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment who elected to take their discharge at the end of the Revolutionary War came with the fall fleet to Nova Scotia which at that time included New Brunswick. The date of discharge for these men can be found in the muster roll of the regiment taken from 25th August to 24th December, 1783 … The 42nd Royal Highland Regiment was one of the last regiments protecting the embarkation of the Loyalists. It seems very likely those discharged came directly to New Brunswick in October 1783. They drew lots and spent the winter in the Town of Parr and Carleton (Saint John, New Brunswick). Twenty-eight men of the Black Watch are registered in the town plan for Parr and eleven in Carleton. The following is a list of the 42nders who were included in the register of lots in the town of Parr and Carleton in 1784-85. The lots were approximately 50′ by 100′. In Parrtown most were on Pitt Street and in Carleton they were on St. John’s Street and Water Street”:

Town of Parr Town of Carleton |

Duncan McKay / Donald McLean |

Duncan McCrae / James Forbes |

George Blair / Peter McLagan |

Daniel Ross / William Munro |

Donald McDougal / Malcolm McIntosh |

David Bruce / Donald McDonald |

Alex McDonald / Donald Urquhart |

John Pebles / Angus McBean |

James Cameron / John McFarland |

Donald McKenzie / Dugal Campbell |

John Mckenzie |

James McNab |

James Ross |

Andrew Sproul |

George Pebles |

Robin McKay |

Daniel McKay |

Daniel McLeod |

John Fraser |

Henry MacKay |

William McPherson |

William McKay |

Francis McKay |

John Sutherland |

Daniel Robertson |

John Wouer |

John Sutherland |

Duncan McLeod |

Note: Alexander McIntosh of the 71st Regiment also registered at Town of Parr. Alexander Drummond of the King’s American Regiment also registered at Town of Carleton. Ann Drummond and Jacobina Drummond also registered at Town of Carleton.

“… Upon their first arriving at these locations the land was covered with a dense growth of spruce trees. The highlanders proceeded to cut down the trees and clear the land and build log houses to shelter themselves and their families. Very likely they spent the severe winter on a diet of salt pork and biscuits. In June 1783 a fire destroyed Parrtown and the 42nders were forced to move to their grants on the Nashwaak. Other regiments had been ordered out of Carleton and it appeared therefore that the orders applied to the 42nders as well. The civilian Loyalists wanted the land in Saint John. Not all 42nders were happy to go to the Nashwaak … The 42nders left Saint John and went up the St John River to the land allotted to them on the Nashwaak… it was one of their own officers, Lieutenant Dugald Campbell, who planned their settlement and surveyed the land. The lots or plantations surveyed were in the Parish of St. Mary’s on both sides of the Nashwaak River from 240 rods below the Tay River (Macktaquack) to 56 rods (14 chains) above the mouth of the Cross Creek (LaBudagan River). The warrant to survey this land was granted August 31, 1785 and the land was granted June 7, 1787 … The land was divided into 185 lots. It was in two tracts … The lots in tract two were small … Several petitions made by the grantees are in the New Brunswick Provincial Archives. Petition number 438 from John Ross said that ‘he was poor and went away earning money’ and his lot had been assigned to someone else. … Another petition by four memorialists, John McLeod, John McKay, Roderick McLeod, and Mordick McLeod, March 30, 1787 asks for additional land. The Council decided that … ‘the disbanded soldiers of the 42nd Regiment who are dissatisfied with their present narrow allotments may dispose of the same and apply for 200 acres each as Loyalists, but can have additional allotments on no other conditions’. According to Esther Clark Wright in Loyalists of New Brunswick 19 moved to the Miramichi and 11 moved elsewhere … Patrick Campbell visited the settlement in 1792. He wrote a book about his travels and gave a very interesting account of the territory and the people he visited on a trip to the Miramichi.

‘Here I was told that the highlanders settled up the river were in many respects not a whit better than real Indians, that they would set out in the dead of winter with their guns and dogs, travel into the deep recesses of distant forests; continue there two or three weeks at a time, sleeping at night in the snow, and in the open air; and return with sleds loaded with venison, yet withal were acknowledged to be the most prudent and industrious farmers in all this province of New Brunswick, and lived most easily and independent’

He mentions dining with ‘Angus McIntosh the highest settler on the river’. His wife said that they had everything they needed but she wishes to have some heather to plant near her house. “

From And the River Rolled On – Two Hundred Years on the Nashwaak |

Published by the Nashwaak Bicentennial Association

Excerpt from Pages XII and XVII

“… An Irish army officer noted in 1813 that thirty years after their arrival in New Brunswick, the Highlanders spoke the Gaelic in all its purity. An old Indian trail called Nashwaak Portage led from the Nashwaak to Miamichi Valley. It left the river near Alex McIntosh’s house and went via Cross Creek, Clearwater Brook and Taxis River Valley. A number of Scots families crossed Portage in search of better land, and generations of their descendents have continued to move back and forth, keeping in touch with relatives and friends. Some families from Loyalist settlements farther down Nashwaak also obtained lots on SW Miramichi. … When the province began to build a highway system to make it easier for people from far distant parts of province to travel to Capital, the road up Nashwaak, over Portage and down Miramichi to Newcastle became one of the Great Roads of New Brunswick. … The religious affiliation of many of early settlers is not known. Alex McIntosh was described by a descendent as having been ‘a Protestant but not a Presbyterian’. It is likely that he belonged to a breakaway sect from he Episcopal Church of Scotland called the Non-Juring Episcopalians; ministers of that church were prominent in Highlands in early 18th century. “

Excerpt from Page 104

“… When the land on Nashwaak was granted to the discharged soldiers of 42nd, two lots 91 and 92 … each containing 62 acres, were set aside for burial. … the first part to be used was next to the Nashwaak. This part now looks as if it had fewer graves than the remainder but first graves had few headstones and were more apt to be of wood, which soon rotted away, or a flat stone on its edge. “

42nd Regiment on the Nashwaak – Registered June 1787 – 17,400 Acres

Grantee | Lot Numbers |

McKay, Duncan | 26 and 28 |

McLeod, Duncan | 157 and 160 |

McRaw, Duncan | 17 and 18 |

Munro, William | 36 |

Robertson, Donald | 104 and 105 |

Burial Ground | 91 and 92 |

Excerpt from Page 105

FOR THE 42ND

This is a quiet place.

Water glimmers through the lace

of branches, but the river

is too far off to hear;

only when the wind is roaring above the valley

or spades announce

with ring on rock and thudding sods

the locking of descendant’s limbs,

is the silence broken. Imperceptibly, the smoothening stones

lean down

over bundles of old, green bones.

No vision or memory

recalled the seer’s prophesy

when men who stood up on those bones

tore at tangled barricades,

smelled sweat of fright and musket-smoke,

heard clattering roll of fusillades,

close screams of death

before they broke

at Ticonderoga.

The lament, Lochaber No More, lifted and faded,

a portent on the wind.

Another war, and they returned:

Long Island, Harlem, White Plains,

the South … All that remains

are the words of history;

nothing of meadows brushing bare knees,

the taste of dust on Carolina roads;

leaping of blood to pipes’ sky-piercing vaunting, wild

short-breathed charge

in first light of morning;

campfires at dusk,

silhouettes moving, talking.

Finally, they settled here;

cleared land, made families,

and died.

And now, who remembers

them, or the places whence they came?

Sea-lochs and glens

from Wester Ross to the Mearns

were in their eyes and speech …

Leaves drift across the graves;

there is no way to reach

back down the years.

Only their names

remember.

By Robert Cockburn

From The Saint John River and Its Tributaries by Esther Clark Wright |

Excerpt from Pages 147 and 148

“… Beyond Marysville, the Nashwaak runs through hills which are very gorgeous in their autumn colouring. Then the valley widens into farming country, where there are meadows and back roads to explore, up the Penniac and other little streams. The largest tributary, the Tay, was named by Jacobina Drummond, wife of Lieutenant Dugald Campbell of the 42nd, and sister of Alexander Drummond, who had been surgeon in the King’s American Regiment. A block of land in this region was granted to the officers and men of the 42nd Regiment, later known as the Black Watch. Some of the Highlanders who came with the Loyalists in 1783 had been settled in upper New York Province after their participation in the French and Indian Wars. Others had come from Scotland to fight in the Revolutionary War. The Bruces, Camerons, Gunns, Munns, McCaulays, MacKays, MacKenzies, MacLaggans, MacLeods, MacMillans, McRaws, Roses, Stewarts, Sutherlands and Yeldens moved on to the Miramichi to join the Scots who had settled there. The Campbells, Abernethys, Frasers, Kennedys, Munros, MacBeans, MacDonalds, MacFarlands, MacGregors, MacIntoshes, MacIvers, some MacKays, MacKenzies, MacLaggans, MacLeods, Rosses, some Sutherlands, Urquharts and Wilsons remained on the Nashwaak. “

From The Black Watch by Archibald Forbes |

A History of the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) Formerly Styled the 42nd (The Royal Highland) Regiment (The Black Watch).

Excerpt from Page 43: Service in North America 1756

“… War against French in North America formally declared in May, 1756. Expedition in two divisions sent from home, landed in New York June, 1756; first division commanded by Major-General James Abercromby, of which Lord John Murray’s Highlanders formed part. Later came Lord Loudon, as commander-in-chief in North America. Washington’s futile attempts to stir the sluggish Loudon to active campaign. Montcalm active and successful; Highland Regiment inactive in Albany during 1756. Regiment in 1757, 1300 strong – all Highlanders. Loudon recalled, because of delays and inertness. Termination of inglorious campaign of 1757. “

Excerpt from Page 49: Ticonderoga 1758

“… Loudon succeeded by General Abercromby. Brighter prospects. Expedition against Fort Ticonderoga, commanded by Abercromby with 15,000 men. Fort on tongue of land, surrounded on three sides by water; fortifications very strong. Garrison 5,000 men. On July 5th, 1758, Abercromby disembarked at head of Lake George, and marched in four columns towards forts. In skirmish on march was killed Brigadier General Viscount Howe. On morning of 8th, believing assault practicable, Abercromby engaged, although guns not up. Place found very strong, with regularly constructed breastworks, abatis, and other defenses. First attack failed, then Highlanders rushed forward from reserve, and assailed with great fury. Desperate struggle lasting four hours. Highlanders reluctantly withdrew after loss of more than half of strength and of 25 officers. Returned in good order unmolested, 647 officers and men of Black Watch hors de combat. Intrepidity of Highlanders admired greatly. Remains of regiment covered retreat and brought off wounded. Arrival of reinforcements to fill depleted ranks. General Stewart’s comments on impetuosity of Highlanders. Highland characteristics. “

Excerpt from Page 59: Martinique and Guadeloupe 1759

“… Recruitment; O’s and Mac’s – names of men with O prefacing names changed to Mac. Second battalion sent to West Indies with expedition destined for Martinique and Guadeloupe under General Hopson, January, 1759. Citadel of Port Royal. Fort Negro captured. Army landed January 16th. Venue changed to Guadeloupe. Fierce attack on Basse-Terre, capital of island. Town in blaze. … Storm off Fort Louis. General Hopson’s death; his successor General Barrington. Surrender of island by French troops and inhabitants, May 1st. Severe loss from climate. “

Excerpt from Page 67: North America 1759

“… In May 1759 first battalion joined force under General Amherst, designed to take part in renewed attempt on Ticonderoga. Second battalion joined from West Indies. Total strength of force 14,500. Preparations begun for attack on Ticonderoga. Siege actually begun when French Commander abandoned fort and withdrew. Further operations prevented by want of shipping; two vessels built; but winter set in, and army spent winter at Crown Point and Ticonderoga. Result of campaign of 1760 was cession of Canada to Great Britain, following on combined movement punctually accomplished on Montreal. French Governor-General surrendered; ten French battalions became prisoners of war. General Amherst made peer. Submission of inhabitants. “

Excerpt from Page 71: Martinique Once Again 1762

“… Troops ordered from North America to West Indies in summer of 1761. … Arrival at Barbados. Rodney’s fleet in St. Ann’s Bay; partial landing of troops. Capture of Morne Tortueson after stubborn contest. Folly of garrison of the Garnier. Brilliant and successful assault by Highland soldiers.

Excerpt from Page 74: Conquest of the Havannah 1762

“… Formidable expedition to the Havannah. Admiral Knowle’s survey of vicinity. Earl of Albemarle commander-in-chief of land forces, Admiral Pocock commanding fleet. … fortress of ‘Moro’ very strong and commanded crowded harbour. Spanish militia successfully attacked by Albemarle. Difficulties encountered in making approaches. Repulse of sortie. … Failure of Captain Hervey’s project. Burning of besiegers’ principal battery. Abortive sortie of Spaniards. Successful storm of Moro. Gallantry of Highlanders. Devotion of Spanish chiefs. The guns of Punta silenced. Capitulation of the Havannah. Distribution of prize money. “

Excerpt from Page 86: Fort Pitt and the Backwoods 1762 – 1767

“… From Cuba to North America. Regiment landed in New York in October, 1762. Following winter in Albany. Relief of Fort Pitt. Summer of 1764 in constant patrolling against Indians. Skeleton of regiment, after decade of service in North America, ordered home. Departure regretted in colony because of good conduct. Officers of Black Watch a band of brothers. “

Excerpt from Page 92: Home Service 1767 – 1776

“… Landed at Cork, October 1767. Recruiting in Highlands. Royal Warrant concerning colours. Changes in clothing and arms. Eagerness to enlist. Quartered in Glasgow after absence from Scotland of 32 years. Peculiar regimental administration. Lord John Murray’s devotion to regiment. Pride in grand old corps. Embarked for North America at beginning of War of Independence. Embarking strength of rank and file, 1,012. “

Excerpt from Page 99: War of Independence 1776 – 1782

“… May 1, 1776, regiment, along with Fraser’s Highlanders, embarked for America. A transport captured by American privateer. The Highland company rose against American crew, and navigated the transport to Jamestown. Republican Government made prisoners of Highland Company, men of which rejected all inducements to forfeit allegiance. Battle of Brooklyn gained by Howe – American loss 3,300 men. Washington’s activity. Storm of Fort Washington. Fort Lee reduced. Winter quarters. Defeat by Washington of Hessian garrison of Trenton. Combat of Princetown. Surprise of Highlanders by American force – enemy beaten off. Movement of British Army to Chesapeake. Battle of Brandywine – defeat of Washington. Entry into Philadelphia of British troops. General Howe succeeded by General Clinton. Destruction of American privateers by General Grey. Destruction by Highlanders of American stores at Portsmouth, in Virginia. Highland Regiment deteriorated by draft of blackguards …”

Excerpt from Page 118: America and Home

“… Fortune of war adverse to Great Britain. Siege and surrender of Charlestown. … Regiment’s reembarkation for New York. Loyalty of Highland Regiment; no desertion in five years. Reduction to eight companies. Six years’ stay in Halifax. Presentation of new colours there. Return to England in October, 1789, after fourteen years foreign service. Service in England and Scotland. Troubles in

Ross-shire and Lowlands. “

Excerpt from Pages 121 and 122

“… At close of long war the establishment of the regiment was reduced to eight companies of fifty men each. Officers of ninth and tenth companies were not put on half pay, but were retained as super-numeraries in the regiment to fill up vacancies as they occurred. Many of the men were discharged at their own request, and their places were supplied by those who desired to remain in America in preference to returning home. During the War of Independence the losses of the regiment were 83 killed and 286 wounded. In October 1783, regiment sent to Halifax where it remained until 1786, when six companies were removed to island of Cape Breton, the remaining two companies being despatched to the island of St. John (P. E. I. ). In this year the second battalion was formed into a separate regiment and numbered the 73rd. The 73rd had always upheld the character which it had honourably acquired as foster-brother to the old Highland Regiment and when the system of linked battalions was put in force in 1872 the 73rd rejoiced greatly to be reinstated as second battalion of the grand old corps which now stands in the Army List as ‘The Black Watch’ (Royal Highlanders) … In May, 1787, Lord John Murray died in his 77th year, and in his 42nd year of his command of the regiment. At time of death he was senior officer of the army. He was succeeded in the command of the Royal Highlanders by Major-General Sir Hector Munro on June 1, 1787. Sir Hector was the descendant of the ancient Ross-shire family of Novar.”